Cooking My Way Through the Stephen King Cookbook

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

A few Octobers ago, I enjoyed what I thought was the quintessential Stephen King dining experience. It took place in Dysart’s Truck Stop and Restaurant, a few miles outside Bangor, Maine. Halloween was looming, fall was tipping into winter, and the dining room was a foggy huddle of flannel and L.L. Bean duck boots. The pie à la mode was blueberry, and it steamed gently next to my battered copy of Under the Dome—a book that begins in an eatery not unlike Dysart’s. Gripping as the story was, my attention couldn’t help but wander to the nearby conversations, listening out for every ayuh and yessah.

If this sounds like a British guy indulging in appalling cliché, I can only promise that I do remember the meal that way. My time in Bangor was marked by many such slippages between reality and memory and fiction. I was on a horror-lover’s pilgrimage, Bangor being both King’s home and the setting for IT, my favorite novel. Clown-haunted Derry is Bangor in all but name; King changed the street names, but kept most everything else. I had spent the day roaming sights that I thought only existed in my imagination: the Barrens, the Standpipe, Up Mile Hill (called Hammond Street in this weird, real-world variant), and the eerie fiberglass grin of the Paul Bunyan statue in Bass Park. Even Dysart’s itself is featured in more than one King story.

It's perhaps forgivable, then, that I mythologized that blueberry pie. I can’t really recall how tasty it was, but in my mind it’s The Pie that stands for all pies, my Americana fetish on a plate, the final flavor of an uncanny day. Food does that, doesn’t it? It grafts itself to memory with a tenacity that only teenage love songs can rival. Now, each time a restaurant or diner or a meal of any sort is mentioned in a Stephen King story, I’m transported back to that Formica table, with the New England night falling softly outside.

Food and story, memory and imagination—these abstract impressions can intertwine. It’s a phenomenon that Theresa Carle-Sanders understands well. She puts it to good use in Castle Rock Kitchen.

What a mad idea a “fictional cookbook” seems at first consideration. These are recipes inspired by characters who never lived, who have never eaten the food described. The meals themselves may only appear as a fragment of a sentence or a throwaway bit of local color. Carle-Sanders’ book is handsomely presented, with a gorgeous map of Maine, full-color photos by Jenny Bravo, and even a foreword from King himself. She even adopts a fictional framework for the delivery, writing from the perspective of Mrs. Garrity, mother of The Long Walk’s protagonist, Ray Garrity. It’s a deep cut reference immediately alerting you that Carle-Sanders has done her homework. Despite all of that, I’ll be honest—when presented with Castle Rock Kitchen, my first thought was “cash grab.”

How lucky then, that during a cursory riffle through the pages, my eye caught on a recipe for something called a "Blue Plate Special." I say “something” because, having prepared Carle-Sanders’ version with questionable success, I’m still aware that the dish means many things to many people. A quick bit of research reveals that the term was widely used in the first half of the twentieth century to describe a rough-and-ready diner offering. The plate itself was the only constant: traditionally blue, inexpensive, and segmented like a TV dinner tray. What was served on it changed daily. Often, it would be leftovers from the previous day, repurposed into a cheap, hearty meal for those on the move.

This is precisely the kind of unpolished American food that speaks to me. A dish like the Blue Plate Special is tinged with history; it’s almost folkloric. You can easily imagine John Dillinger chewing one down, or Jack Kerouac scraping the blue enamel clean before dashing off for one coast or the other. Carle-Sanders accompanies each of her recipes with a snippet from a King novel, and it’s no coincidence that here she chooses to reference 11/22/63, in which time-traveler Jake Epping eats in “a lot of roadside restaurants featuring Mom’s Home Cooking, where the Blue Plate Special, featuring pie à la mode for dessert, cost eighty cents.”

11/22/63 is a celebration and a lament. Of all King’s novels, none reaches with greater longing for an era that is gone, or perhaps never existed in the first place. Thousands of miles and an ocean away, on my tiny, cramped island, I too remain a little bit in love with the myth of this lost America. I found a slice of it on that late October afternoon in Dysart's, and now, Carle-Sanders’ cookbook was offering me the opportunity to make another using some potato stuffing and pan-fried chicken thigh.

I won’t say the results were breathtaking. My chicken gravy certainly turned out less luscious and velvety than the photo, and I have no idea how close my cobbled-together version of “Bell’s Seasoning” came to the real thing. In reality, the meal ended up as some strange hybrid of Thanksgiving dinner and the fried-up leftovers we Brits call bubble and squeak. It was tasty though, and between bites I tried to close my eyes and imagine myself in some rustic Maine diner, big rigs rolling on the highway outside, heading for Castle Rock, or Derry, or Jerusalem’s Lot.

Emboldened by my meager success, I settled on the project of cooking my way through the other eighty recipes. It didn’t seem too difficult a proposition at first. I once devoted an entire year to a chronological re-read of King’s 75 published works. When you consider how many of those books top out at over eight hundred or a thousand pages, even the most complex of Carle-Sanders’ recipes seems a short-lived challenge. Of course that’s a ridiculous comparison, even before you factor in the chances of locating Maine maple syrup and fiddleheads in a British supermarket. Also, having spent a week cooking up a good dozen of these recipes so far, I have serious questions for whoever chose the “cup” as a standard unit of measurement. Picture me this most recent Sunday, beet-faced and exasperated, demanding to know how the hell you measure leeks in a damn CUP!

Culinary culture shock aside, it was almost as difficult to decide which was the more important criteria: the recipe or the source material. Some of these links are extremely tenuous—do we really need a recipe for mac ‘n’ cheese simply because the dish is namechecked in the obscure “Gramma?”—but some are delicious enough that I can forgive the author for stretching. A Dutch pancake with banana-pecan compote is unlike anything I’ve ever eaten. Gloopy and spongy and syrupy, like unrisen batter. It tastes divine. Does it really have any relevance to IT bar the briefest of mentions by Richie Tozier’s father? No, but who cares? My wife and I have eaten “Pancakes with the Toziers” three Sunday mornings in a row.

Other recipes have a more substantial basis in King’s fiction. Potato and collard soup is derived from The Long Walk, where it’s an essential meal in a dystopian world. Carle-Sanders’ version is easy to make and insanely good, considering how few ingredients it contains. “Sloop” is a Revival-inspired corn chowder that looks utterly disgusting, but coats the tongue beautifully—though again, I used my garden-gathered approximation of Bell’s Seasoning (is this a thing in Maine?).

I can’t recall what Dolores Claiborne ever cooked for her abusive husband and nightmarish employer, but "Sunday Boiled Dinner" and starchy oven-baked risotto at least feel like something that this brave, beleaguered woman would prepare (and perhaps spit in before serving). The most appetizing recipe in the entire book is “Poor Man’s Soup,” a lobster bisque mentioned in one of King’s best ever short stories, “The Reach.” I have yet to make it myself because we’re in the middle of a financial crisis here in the UK and the price of a pair of lobsters would indeed make me a poor man, but one day…

So far, it was a fun and lightweight project. But when I was itemizing these more faithfully Kingian dishes for a shopping list, I realized that they share certain features. They are meals cooked within a tight budget, using what is readily available, and often marked by shame and defiance. As Stella Flanders explains in “The Reach,” “We always used to have a pot of lobster stew on the back of the stove and we used to take it off and put it behind the door in the pantry when the minister came calling so he wouldn’t see we were eating ‘poor man’s soup.’”

How interesting, I thought, that the meals King wrote about in greatest detail—the recipes that Carle-Sanders was able to lift more directly from the page—are the “poorest” food, often cooked by mothers or sturdy oh-so-Maine ladies like Stella Flanders. Then it struck me that these were perhaps meals that King’s own mother cooked for him. I won’t rehash the details—if you want to know more about King’s financially precarious childhood and his tough-as-hell mother, Nellie Ruth King, I suggest you read On Writing. But suffice to say, she worked hard to provide for him and his brother, and he loved her very much. I am speculating wildly here, but I thought again of how food and story and memory can fold together in the human heart.

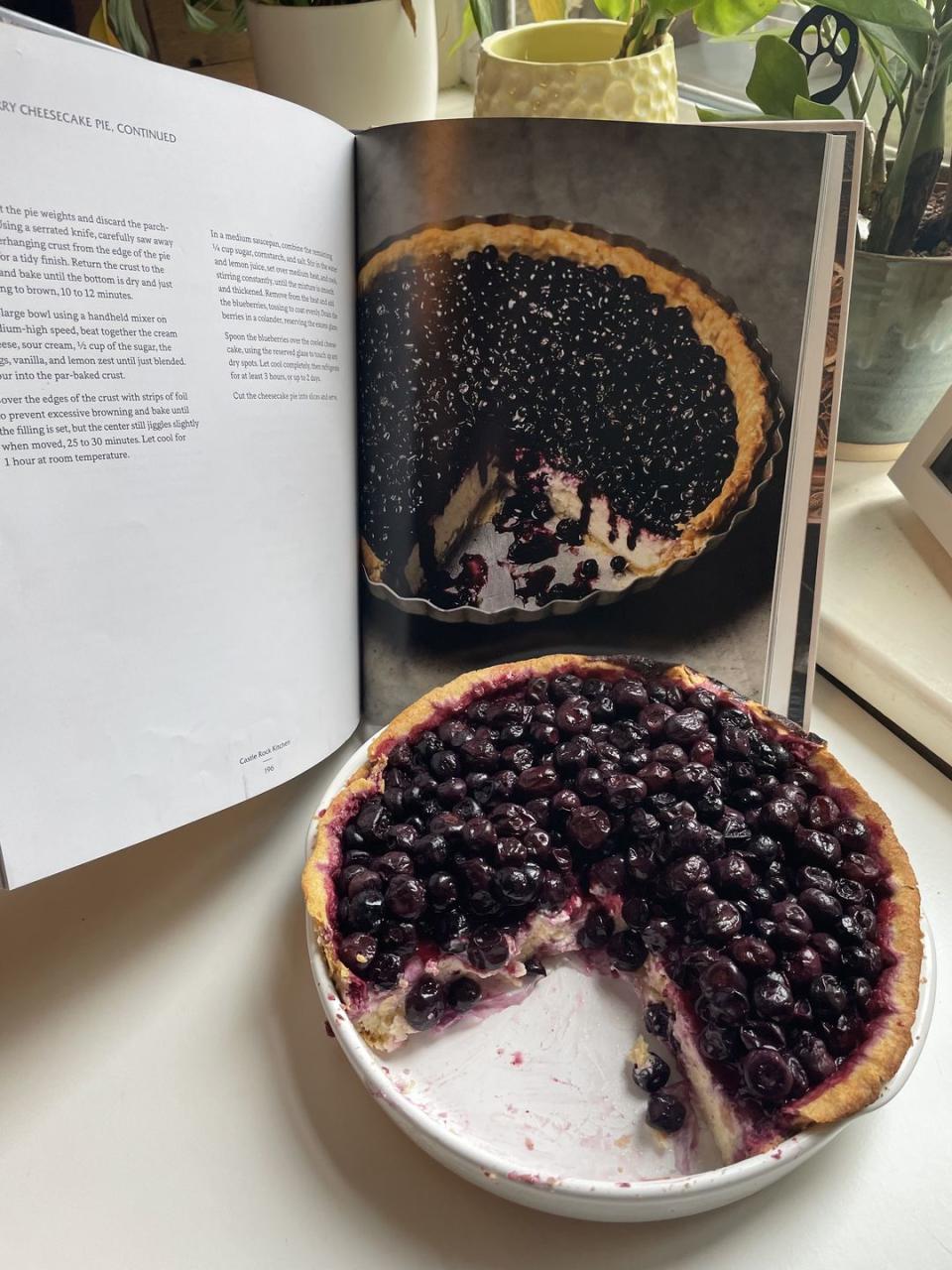

What started as a gimmicky side-note to King’s stories suddenly became something more profound. Each of the dishes I tried my hand at—"Dick Hallorann’s Baked Beans" from The Shining, “Vegan Chili at Jon’s” from The Dead Zone, even a bungled attempt at a blueberry cheesecake pie inspired by “The Body”— felt like a trip into King’s tilted version of America, and a communion-of-sorts with the man himself.

I know, this likely sounds like utter bullshit, but it’s not. I have been reading and re-reading Stephen King all my life. I wrote a PhD about him. I have visited his hometown, taken the Stephen King Tour, and even couch-surfed in a house literally across the street from his. (Side note—this was a happy accident, not a stalking attempt.) Eating this food was the first new way into his fiction that I’ve found in years.

I’ll always remember eating that pie in Dysart’s. Now, though, it will not be my only go-to image when King writes of diners and truck stops and old men gathered in the local store. I may have approached Castle Rock Kitchen with mild disdain, but it proved to be a new doorway into my favorite universe—a way to participate just a little in the honest, working-class American life that King has always cast as the bulwark against darkness. Not everything in King’s world is frightening, after all. Sometimes there are tables in a warm place, something delicious to eat, and mothers to remember.

You Might Also Like