How the College Admissions Scandal Is Different from Other Ways Rich Parents Help Their Kids Get Into School

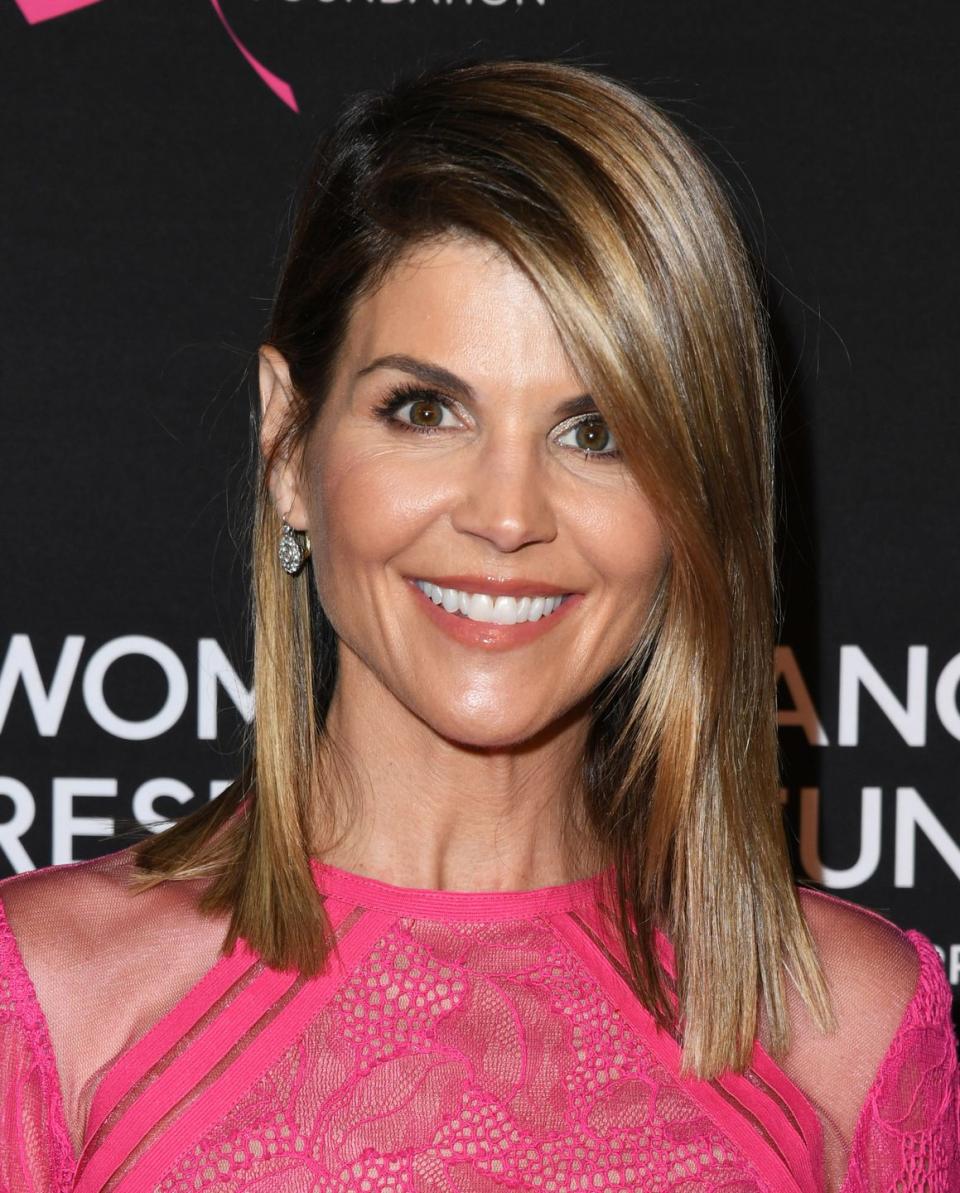

On Tuesday, March 12, 2019, the Federal government indicted William Singer, a college admissions consultant based out of Newport Beach, California, and 33 other parents including Lori Loughlin and Felicity Huffman, for crimes that included bribery and racketeering for purpose of fraudulently getting children into college.

While there is a culture of paying one’s way into an upper echelon school that is quite pervasive, the Varsity Blues bribery scheme explicitly sought to find spaces for the children in exchange for money, via Singer as conduit.

William Singer pleaded guilty in a federal court on Tuesday, March 12, while Felicity Huffman was indicted that same day. Lori Loughlin turned herself into federal authorities on Wednesday, March 13.

Last August, YouTuber Olivia Jade posted a video for her 1.9 million subscribers. She was moving into her college dorm that day at the University of Southern California, but Olivia reminded her viewers that YouTube was her real passion: “I don’t really care about school, as you guys all know.”

Olivia Jade established a significant following online. Fans regularly asked her about her famous parents, actress Lori Loughlin and fashion designer Mossimo Giannulli. Over the past few years, Olivia documented her daily style routines, answered fan questions, nabbed sponsorships from beauty and retail brands, and peppered in videos featuring Loughlin and her Full House co-star John Stamos. This pattern continued once she started at USC, but according to federal prosecutors, there was a seedy backstory to how the young influencer was accepted to that elite university.

Loughlin and Giannulli connected with William "Rick" Singer, a college admissions consultant based in Newport Beach, California. Singer promised to secure admission to USC for their daughters as recruits for the university’s crew team, even though neither participated in the sport, according to prosecutors. Singer would arrange fake athletic profiles for the girls, the feds say, and Loughlin and Giannulli just needed to send him pictures of their daughters using ergometers.

The parents had to send $200,000 to Singer through the Key Worldwide Foundation, a non-profit he controlled, for each daughter, plus $50,000 per kid to USC senior associate athletic director Donna Heinel.

The famous couple were among 33 wealthy parents indicted by federal prosecutors in a massive bribery and racketeering case that the US Department of Justice called the largest college admissions scandal it had ever dealt with. Between 2011 and 2019, according to a criminal complaint, Singer collected $25 million through the scheme from big wigs in various industries, including a gaming executive, a Napa Valley vinter, the co-chair of an international law firm, a prominent Silicon Valley investor who advocates for social responsibility, and actress Felicity Huffman. All of them, the feds say, paid to either have Singer’s cronies help them cheat on the ACT and SAT college admissions tests, to nail a spot at elite universities by pretending to be athletes, or both.

“We’re not talking about donating a building so that a school is more likely to take your son or daughter,” Andrew Lelling, the US attorney for the District of Massachusetts, said at press conference on Tuesday. “We’re talking about deception and fraud.”

How Is This Different From the Usual Ways Wealthy Parents Help Their Kids Get Into College?

Lelling’s quote contrasting the alleged bribery scheme with buying a building caught significant attention. Journalists called it “illuminating,” and some reacted with snarky tweets: If the FBI wants to continue its investigation, they might start by looking at names of buildings on a campus, which is how “rich people buy their way into the Ivy League the old fashioned way.” The whole episode touches on an existing undercurrent that too much of society is rigged for the benefit of the rich and privileged in what is supposed to be a meritocracy.

“Many people believe that there is often an unspoken quid pro quo with respect to big donors and family members and we’ve seen instances where that appears to be true,” said Theodore Shaw, a former director-counsel and president of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund. “This is quite clear quid pro quo, and doesn’t sound like there is much doubt.”

Wealthy families often donate to colleges with the hope, or expectation, that it’ll get their kids a leg up in the admissions process. The recent affirmative action trial involving Harvard put this on display. Documents in the trial revealed how deans celebrated that because of who the university’s admissions office brought in, donors committed to buying a building. But what is different about the alleged bribery scheme, dubbed “Varsity Blues” by the FBI, is that it was much more explicit exchange of holding a recruitment spot for a student in exchange for a set amount of money.

“Neither one of them may be commendable but it seems to me there is a difference between a bribe and a hope,” Shaw told Town & Country.

It’s typically acceptable for a college to favor the kids of donors as long as it’s only one of multiple factors for admission, and because schools promise to use the money to help fund scholarships for low-income students.

A federal court rejected a lawsuit in 1976 challenging the University of North Carolina’s preferential treatment to legacy students, citing that the school had a “reasonable basis” to favor children of alumni who “provide monetary support for the university.” When the US Department of Education investigated Harvard’s admissions practices in 1990, it concluded there was no legal reason that the school couldn’t favor wealthy and legacy students who may bring in more donations.

In college admissions offices, they often flag which applicants come from families that have been financially generous to the school, so that they at least get a close look. The influence by college donors is often much more symmetrical to political campaigns. It’s perfectly legal for a business owner or a lawyer to contribute large sums of money to help a candidate get elected, with an expectation that once in office, they will give the donor the time of day for a meeting or to hear them out. It’s a much different scenario when a donor tells a candidate, I’m giving you this check, and next year you will support that bill.

“But in this case it went beyond the tacit agreement,” noted Erika Wilson, a public policy law professor at UNC-Chapel Hill.

How the College Admissions Fraud Actually Worked

Singer pleaded guilty this week to racketeering conspiracy, money laundering conspiracy, and obstruction of justice charges. After federal agents approached him last September, the complaint states, he attempted to contact several clients and warn them that the heat was on. He then became a cooperating witness, and agreed to call back many of his clients at the government’s direction while agents recorded.

Singer had two modes of operation. On one end, he would arrange for high school students to take the ACT or SAT away from their schools, typically at testing centers he controlled in West Hollywood and Houston. Singer often advised parents to apply for extra time to take the tests by faking a learning disability for their child, according to the complaint. Then he would either arrange for one of his accomplices, who he also paid off, to either take the test for the teen, or correct their answers.

The other process alleged by the feds involved bribing coaches and officials at USC, Georgetown, Yale, and other top notch schools to save a spot among the athletic recruits for Singer’s clients. Rudy Meredith, the former Yale women’s soccer coach, became a cooperating witness, while several others-including USC water polo coach Jovan Vavic, UCLA men’s soccer coach Jorge Salcedo, and Georgetown tennis coach Gordon Ernst-were indicted for their roles.

Once the students were accepted, that’s when Singer would send an invoice to the parents typically asking them to make a $200,000 tax-deductible donation to his nonprofit, Key Worldwide Foundation, to under the official auspices to “provide educational and self-enrichment programs to disadvantaged youth.”

Parents were often overjoyed, as Loughlin and Giannulli were when they received word that their older daughter was officially accepted into USC in March 2017. “We are on holiday in the Bahamas but will gladly handle when home next week,” Giannulli wrote to Singer’s office when given an invoice that month. They decided to repeat the process for Olivia Jade later that year, presenting her to USC as a Coxswain of LA Marina Club Team, according to the complaint.

The charging documents detail how Singer’s scam was nearly busted a few times. For instance, the complaint states that Loughlin wrote Singer in late 2017 after her daughters’ high school counselor inquired whether their college applications had misleading information about them being athletes.

Heinel, the USC athletics official, told Singer in a voicemail to make sure that the girls say that they are walk on athletes and look forward to trying out for the team, the complaint states. She warned that if the high school guidance counselors found out more, “They’ll shut everything down.”

Once the students were admitted as athletes, there was apparently no follow up to see whether they actually practiced. Several parents made sure with Singer that their kid wouldn’t have to actually participate in athletics, according to transcripts of phone calls, and the prosecutors insinuated that the students who got in through these arrangements had little to no idea what was happening behind the scenes.

The case will “open up a can of worms” for the college admissions world, said Peter Lake, director of the Center for Excellence in Higher Education Law and Policy at Stetson University.

“This is insider trading, college style,” Lake said. “It reminds me a little of some of the scandals of the 80s on Wall Street, and it potentially undermines the credibility of just about everybody until they can demonstrate otherwise.”

('You Might Also Like',)