Christie’s Is Selling a Salvador Dalí Watercolor With a Provenance as Fashionable as Its Subject Matter

“Andy Warhol was like parsley. Everywhere you went, he was there,” Diane von Furstenberg once said of the bewigged artist. Turn back the clock 20 years or so more and much the same could have been said of Salvador Dalí, the mustachioed Surrealist and social butterfly who was not one to look down his nose at fashion. On the contrary, he embraced it, and it’s not difficult to see why. It has in common with his own art a preoccupation with time (ephemerality), fantasy, and transformation.

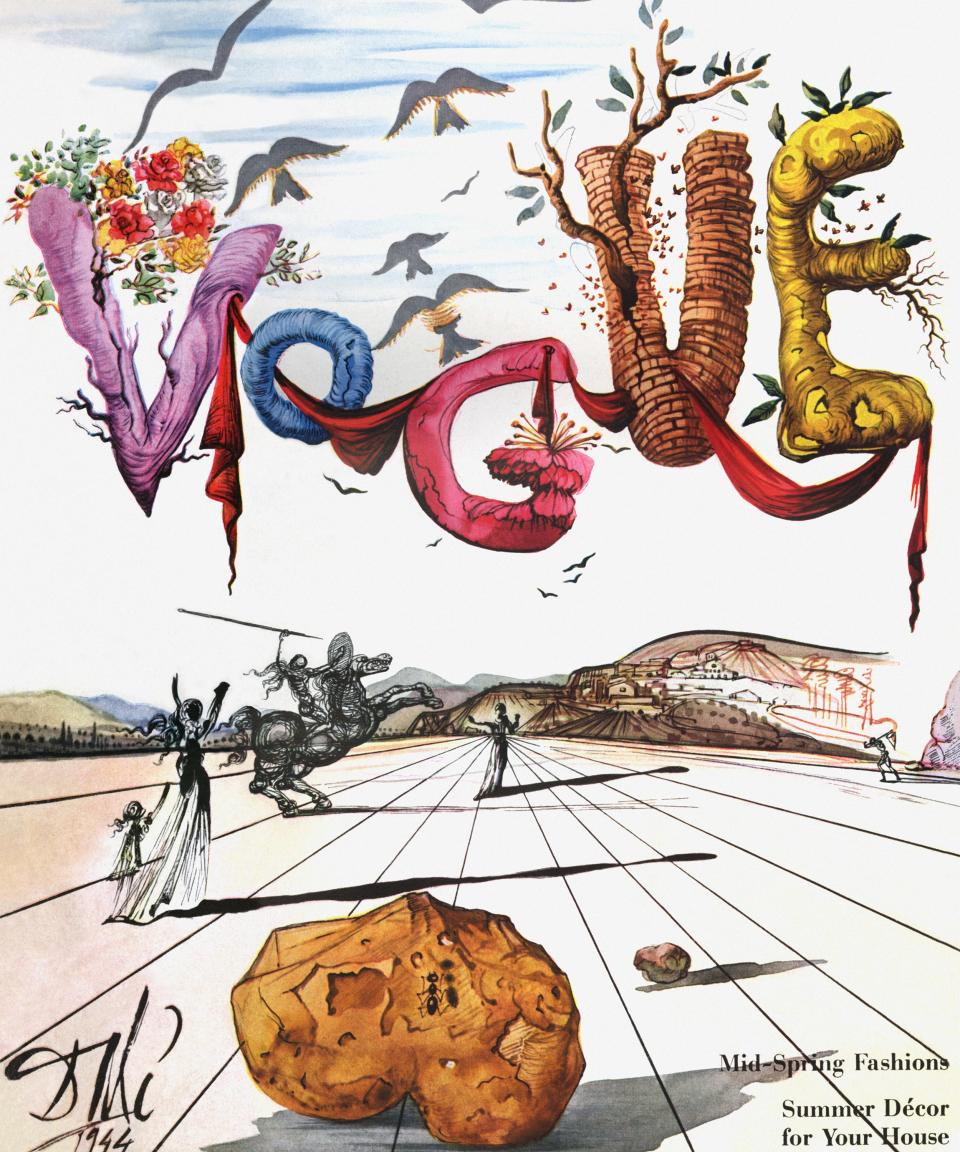

Vogue Magazine Cover

The artist’s best-known engagement with la mode is his work for Elsa Schiaparelli. For the art-mad Italian designer he dreamed up a hat in the shape of a shoe and bureau-drawer-shaped pockets, and he also painted a red lobster on a white dress that scandalized the haute monde when the Duchess of Windsor wore it in 1937. Dalí, as Vogue noted in 1949, was someone “who sparkes ideas in many directions.” He worked with Les Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo; he tried his hand, rather successfully we might add, at jewelry design; and he contributed three covers—and many editorial spreads—to this magazine circa 1939 to 1944.

Surfacing at Christies’s Impressionist and Modern Art Works on Paper sale tomorrow is one of the Surrealist’s most enchanting pieces, a 1953 watercolor titled Femmes aux Papillons. (Dior had laid claim to Femmes Fleurs in 1947.) This stylish work has a very fashionable provenance: It comes from the estate of Eleanor Lambert, who was known as “The Empress of Seventh Avenue” and represented Dalí for a time, among her many other commitments to the likes of the Council of Fashion Designers of America, the Costume Institute, and the Best Dressed List. Lambert accepted this piece in lieu of a cash payment from Dalí. It was likely created, says Allegra Bettini, an expert handling the sale, for the International Silk Conference, with which the artist was working on commercial projects at the time.

Surrealist art—and Dalí’s in particular—is deeply symbolic. The butterfly, like fashion, is associated with fleeting, fragile beauty. But, as Bettini notes, with Dalí nothing is really what it seems. A quick Google image search suggests that the foremost of the collage’s figures might not be a butterfly at all, but a giant silkworm moth—a sly nod to his client at the time. If the radiating perspective lines seem to look back to Dalí’s 1944 Vogue cover (below), the fashions eerily reflect the 18th-century-style flourishes recently seen in the Spring 2020 collections of Rick Owens, Thom Browne, and others. As ever, Dalí is right on time.

Vogue Magazine Cover

Originally Appeared on Vogue