The cause Hollywood forgot: why the Free Tibet movement fizzled out

Halfway up the Argentinian Andes, Brad Pitt brushed aside his blond fringe and took in the spectacular view. It was 1997 and Hollywood’s incredible hunk was playing the part of Heinrich Harrer, the former SS Oberscharführer who in the mid Forties travelled to the ends of the earth to become a mentor to Tibet’s young spiritual leader, the Dalai Lama.

Twenty-three years on, Seven Years In Tibet looms as a Mount Everest of Hollywood activism. As they would have anticipated at the time, Pitt and all the other big names involved in the production were for decades blacklisted by China.

It was a risk they seemed prepared to take in order to stand with the Free Tibet Movement. Free Tibet was at that point the big cause around which the entertainment industry rallied, only for the campaign to eventually fizzle out – at least as a Hollywood talking point.

Today, Black Lives Matter is forcing the industry to revaluate its treatment of minorities and its lamentable record on diversity. This week 300 black artists and executives – including Idris Elba, Tessa Thompson and Michael B Jordan – put their names to a letter urging Hollywood cultural institutions to “break ties with police”.

Meanwhile personalities such as late night host Jimmy Kimmel have issues mea culpas for ‘blacking up” in the past (in Kimmel’s case to lampoon Oprah Winfrey and Snoop Dogg). Closer to home, comic Leigh Francis was reduced to tears apologising for his blackface Craig David and Trisha Goddard impersonations on Bo' Selecta.

This activism already appears to be more than a passing fad. But the Free Tibet movement is a reminder that celebrities aren't quite the effective campaigners they often think they are – and that the window to effect change doesn’t stay open forever. In the end, Tinsel Town was able to do little of substance for Tibet. The hope must be that its long term contribution to Black Lives Matter and racial equality will result in actual change. Because that certainly didn't happen in the case of Free Tibet.

Pitt had gone to Argentina to make Seven Years in Tibet because it was unthinkable that China would allow director Jean-Jacques Annaud film in the real Tibet, which it had annexed in 1950.

The authorities in Beijing would have anticipated that Annaud’s movie would portray China as the villain and its incorporation of Tibet into its national territory as a hostile invasion. Pitt’s character may have been a reformed Nazi (there was huge embarrassment when Harrer’s SS past became public knowledge shortly before the film’s release). In Seven Years in Tibet the Chinese are the real bad guys

Pitt, Annard and co-star David Thewlis are unlikely to have been surprised at their subsequent blacklisting. They may have, in fact, concluded that they were in good company. In 1997 drawing the ire of China over Tibet was the hot new trend in Hollywood. Martin Scorsese was likewise (temporarily) banned after chronicling the early life and flight from Tibet of the Dalai Lama in Kundun, released two months after Seven Years in Tibet, on Christmas Day 1997.

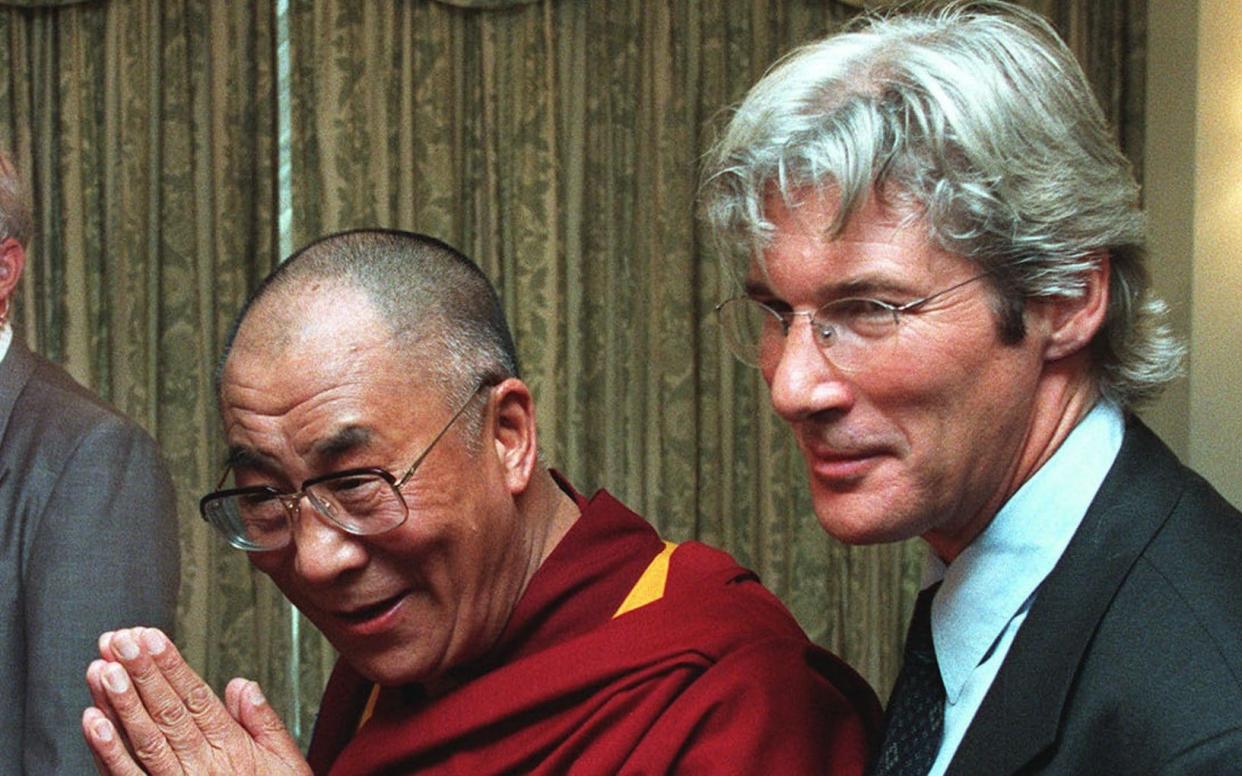

Also on Beijing’s naughty list was actor Richard Gere, converted to the cause of Tibetan freedom on a trip to neighbouring Nepal in 1978 to study zen Buddhism. And then there were the Beastie Boys, the riotous rap trio who turned Free Tibet into a rallying cry for left-leaning rock stars everywhere.

“In the Nineties, the Tibetan Freedom Concerts and films like Kundun and Seven Years in Tibet certainly elevated Tibet’s profile and brought it to a new audience,” says John Jones, campaign and advocacy manager for the London-headquartered Free Tibet non-profit organisation. “You could see cultural references to Tibet on TV programmes like The Simpsons and the slogan 'Free Tibet' was widely known.”.

Alas, in 2020, the cause of Tibetan independence feels very much yesterday’s story, Not much has changed for the Tibetans, who continue to live under Chinese rule. Yet the groundswell of international protest has dwindled to a murmur. So much so that in 2016 the Chinese even put Pitt’s name back on the guest list and allowed him fly to Beijing to promote his World War II thriller Allied. He had lots to say about that movie. On the cause of Tibet independence, he stayed conspicuously schtum.

Today, Tibet is a long way down the list of priorities. As the world takes a stand against racism and its toxic legacy, the fizzling out of Free Tibet is a reminder that the opportunity to affect once-in-a-generation change is a rare and precious thing. It is important to seize the moment because the moment may not come again.

Free Tibet’s ubiquity through the Nineties is hard to overstate. The Tibetan “snow lion” flag , with its streaking red and blue lines, was ever present wherever socially-conscious individuals gathered.

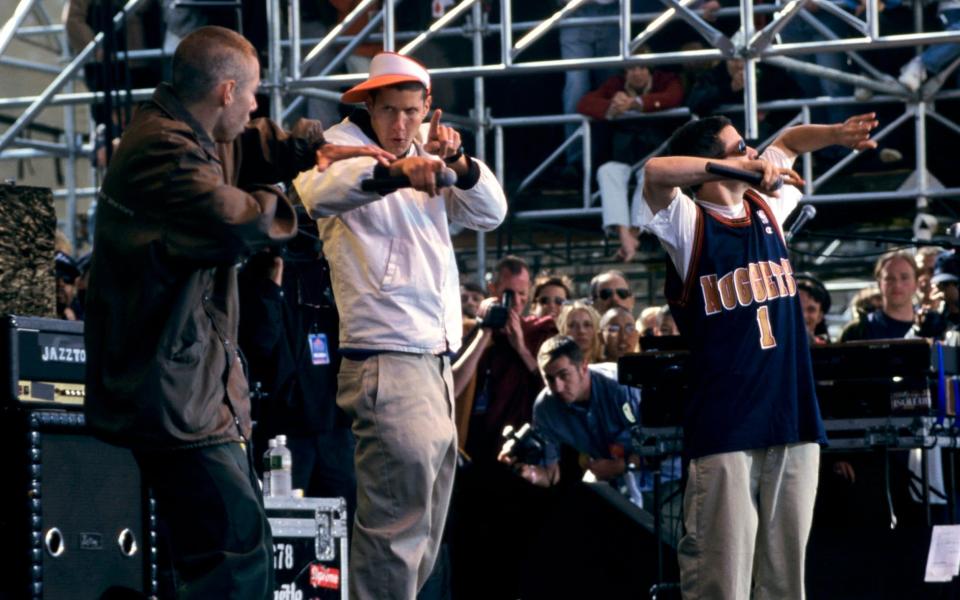

The movement had begun in the late Eighties as protests in Tibet were violently suppressed by China. However, it took the involvement of Beastie Boy Adam Yauch for it to break through to the mainstream.

Yauch was in Kathmandu in Nepal in 1992 when he found himself as a party with a young activist named Erin Potts. “I didn’t appreciate the Beastie Boys music, I guess that’s the most diplomatic way to say it,” Potts told American broadcaster PRI in 2016. "I didn’t want to have anything to do with them.”

Still they got talking and conversation turned to the Tibetan refugees Yauch had encountered around the city. He had been struck by their air of haunted desperation and wanted to know more. He and Potts stayed in touch. Yauch would convert to Buddhism before his death from cancer in 2012 at age 47.

“I’m an activist, he’s a musician,” Potts revealed to PRI. “When you put the two together, what do you get? A benefit concert was pretty obvious as one of the things that we could do.”

China at the time was essentially a regional power. As a market for Western goods and services it was of middling significance. So there was little opposition when Yauch and Potts organised the first Free Tibet Concert at Golden Gate Park in San Francisco in 1996.

A crowd of 100,000 turned up to watch the Beastie Boys, Red Hot Chili Peppers, Bjork, Smashing Pumpkins and others speak out against China. The event raised $800,000 for Tibetan freedom. Other concerts would follow with Thom Yorke of Radiohead for instance singing against the backdrop of a Tibetan flag in 1998.

“Yauch… was instrumental in setting up the Tibetan Freedom Concerts,” says Free Tibet’s John Jones. “At their peak, these concerts featured some of the best known musicians in the world. One of Brad Pitt and Jennifer Aniston’s first public appearances together was at one of these concerts.”

The Dalai Lama meanwhile vied with John Paul II as the world’s most recognisable spiritual leader. With his early life chronicled in two major Hollywood movies he was as much celebrity as religious figure. His 1998 “self help” book, The Art of Happiness, was an international sensation, selling over two million copies.

“The films…presented Tibet’s culture and landscape to western audiences in a way that captivated and intrigued them,” says Jones. “The idea that this pristine environment and this ancient culture could come under attack is cited as a key motivation by a number of our longstanding supporters for their interest in the Tibetan cause. The fact that Kundun and Seven Years in Tibet featured the story of the Dalai Lama, who is easily the most famous Tibetan and is in his own right, definitely helped.”

The Dalai Lama was embraced by Prime Minsters and Presidents across the globe. He also made frequent public appearances with Richard Gere, who, even more than the Beastie Boys, had made Tibetan independence the cause du jour.

Gere did so as some personal cost. He earned the wrath of the organisers of the Academy Awards when speaking out about Tibet at the 1993 Oscars. Invited to present the gong for best art direction, he declined to read from the teleprompter. Instead he condemned China’s occupation of Tibet and the “horrendous, horrendous human rights situation”.

This infuriated Oscars producer Gilbert Cates. He was further angered when Susan Sarandon and Tim Robbins spoke up on behalf of Haitian refugees in the same broadcast. All three were banned from future Academy Awards (only to be later quietly readmitted to the fold). Gere, though, wasn’t for turning and subsequently called for a boycott of the Beijing Olympics. In 2017, he said his career had suffered as a result.

“There are definitely movies that I can't be in because the Chinese will say, 'Not with him,'” Gere told the Hollywood Reporter in 2017. “I recently had an episode where someone said they could not finance a film with me because it would upset the Chinese.”

“Upsetting the Chinese” of course brings with it far more consequences in 2020 than in 1997. As the country’s international influence has grown, so the prominence afforded to Free Tibet has dwindled. No world leader has granted an audience to the Dalai Lama since 2016. And with China on course to become its biggest market, Hollywood is today at pains not to irk it.

Such wariness is understandable. Beijing has showed little hesitation in muzzling films that paint the regime in an unflattering light. James Bond’s Skyfall for instance was delayed from release in China by a year, so that references to prostitution in Macau could be removed.

A 2012 remake of Eighties action movie Red Dawn was meanwhile hastily re-written to depict North Korea as America’s enemy rather than China. And when the cuddly protagonists in 2019 DreamWorks animated feature Abominable travel from Shanghai to the Himalayas, no mention is made of the fact that the mountain range stands in Tibet. It is presented as merely part of China. Twenty-five years ago that would not have happened.

“China’s influence has clearly been growing in recent years, politically but also cultural,” says Jones. “Any Hollywood blockbuster that wants to really bring in the money will need to appear in China. That requires compromises in the films but also careful consideration by the actors – do they really want to put their career at risk by talking about Tibet and China? Richard Gere continues to be a high-profile supporter of Tibet, but he has stated that his stance on Tibet has cost him work.

“The Tibetan Freedom Concerts could conceivably return, even though Adam Yauch had sadly passed on, but it would be tough to get artists of the same profile as those who played in the Nineties. Given the more fragmented way that we consume culture these days, would they attract the same attention?”

Another possible factor in the diminished visibility of Free Tibet is the growing antagonism between Donald Trump and China. Trump swept into the White House on the back of a manifesto that among other things included a pledge to “stand up” to China and diminish its economic influence on America. But his brand is so toxic that many leftleaning activists are understandably reluctant to be seen taking his side.

“The political realities also play their part,” adds Jones. “We are currently bombarded with news of crises around the world that quite rightly deserve international attention, whether it is civil wars like Syria, Ukraine and Yemen or global dangers like climate change and Covid-19.

“The harsh reality is that Tibet has to compete for attention with these crises, and one thing Tibet lacks is coverage; China has closed it off from the world, making it impossible to visit without a guide, and closely monitors Tibetans’s phone and internet activity so that as little information as possible gets out. Getting information out of Tibet is as tough as getting information out of North Korea these days, and if people don’t hear the stories, they won’t be engaged or keen to help.”