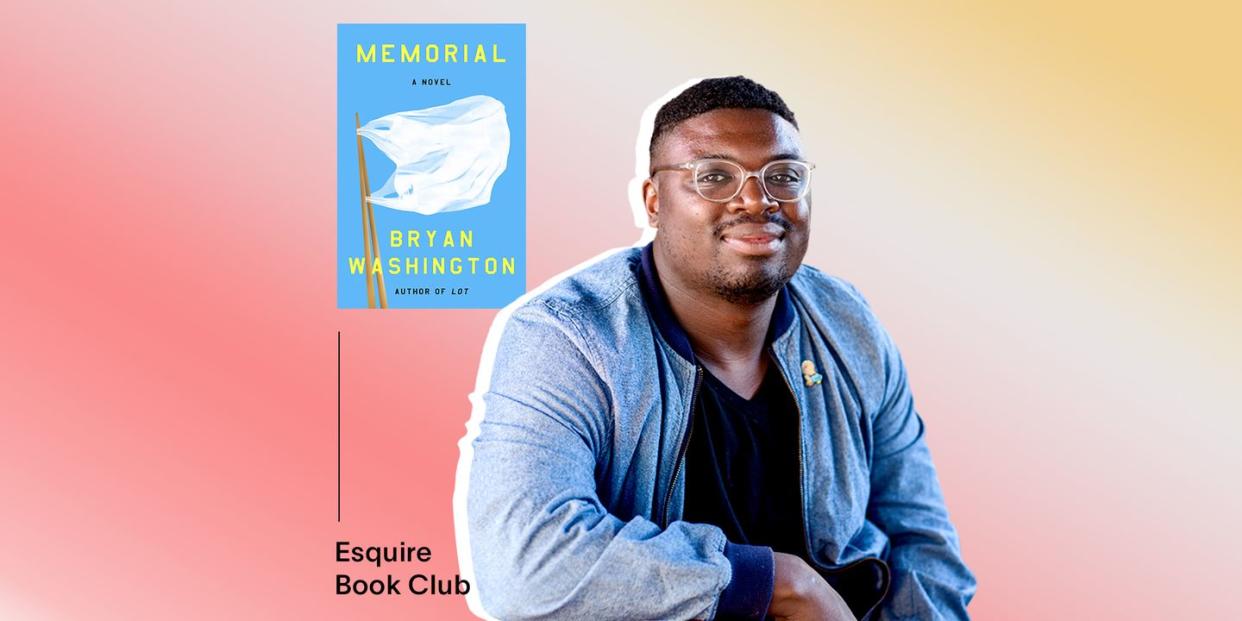

For Bryan Washington, Writing His Debut Novel Meant Perfecting His Rolled Omelet

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

“A story is an heirloom. It’s a personal thing,” chides Mitsuko, one of the three characters at the heart of the triad in Bryan Washington’s Memorial. “You don’t ask for heirlooms. They’re just given to you.”

Memorial is a novel packed with heirlooms—unbidden gifts of care, cooking, and grace. They scatter from Washington’s pen like jewel chips, forming a dazzling tapestry of the places, people, and meals that make us. Drawn together in Memorial, they make for a literary magic trick, a vivid and poignant portrait of how love, romantic and familial, is weathered and ultimately deepened by time.

At Memorial’s center are two complicated men: Benson, a Black daycare teacher, and Mike, a Japanese-American chef. Benson and Mike’s years-long live-in relationship is on the rocks, with each one of them too apathetic to rekindle their romance or to end it. As Mike puts it: “We fight. We make up. We fuck on the sofa, in the kitchen, on the floor. I cook, and cook, and cook.” Their companionable stasis is turned upside down when Mike receives news that his estranged father is dying in Japan just as his mother Mitsuko arrives on their doorstep, forcing Benson and Mitsuko to become unlikely roommates in Mike’s absence. What follows is a bittersweet meditation on love, care, and what it means to be home.

Memorial is Washington’s first novel. His debut collection of interconnected short stories, Lot, was published to great acclaim in 2019, netting him the Dylan Thomas Prize and a nomination to the National Book Foundation’s prestigious “5 Under 35" list, as well as a coveted spot among Barack Obama’s annual favorite books of the year. A24 is set to adapt Memorial for television, with Washington signed on to write the screenplay. Washington spoke with Esquire about telling city stories, crafting culinary character arcs, and how writing Memorial helped him perfect his rolled omelet.

Esquire: In Benson and Mike, you present two delightful, but very different voices. How did those voices emerge, and how did you develop them as the novel progressed?

Bryan Washington: A lot of it was just drafting over and over and over again. I knew from the outset that Benson and Mike and Mitsuko would be the triad at the center of the novel. I also knew that I wanted Ben and Mike to have near equal credence on the page, each with just as much agency as the other. In the end, Benson has about 1,100 words more than Mike over the course of the book. I was trying to get it as close to equal as possible.

It was really important to me that each of them got to make their case, so to speak, and that the reader was left seeing each of them in their totality. I didn't want someone to walk away from the book thinking, "This relationship worked or didn't work because of Benson," or, "It worked or didn't work because of Mike." I wanted to put their lives on the page and allow the reader to make their own decision from there.

ESQ: You’ve said that you envisioned this novel as a “gay slacker dramedy.” The romance between these two men is intoxicating, but I love how you take the “will they or won't they” of it all and leaven that with humor. What’s the relationship between comedy and drama, for you? Is that an important duality in your writing?

BW: I think they're intertwined in a lot of ways, because at some point, extreme drama becomes humorous in and of itself. If humor is just the combination of two things for an unlikely result, then drama is inherent in that equation. What was really important to me with Memorial was having the simultaneous existence of both the challenging moments that Benson and Mike endure, as well as the lighter moments, that are perhaps inside of those challenging moments. I didn't want to choose from one tone or another; I wanted to paint a portrait with a number of different layers.

ESQ: In this novel, the things the characters don't talk about are arguably stickier and more provocative than what they do talk about. What makes the things left unsaid such fertile creative territory for you?

BW: I'm really interested in the space in between dialogue, and also the space in dialogue where there are misconnections or mistranslations. Navigating the gaps in those spaces for each of the characters was really fun to explore, whether that was from cooking and trying to impart comfort and pleasure, or through texting and sending one another pictures. I was really interested in the ways that characters seek out communication, and the way that they gravitate toward one another, even if the language they have isn't doing it for them.

ESQ: The texting and the pictures are so fascinating on the page—how those images operate almost like a shorthand for what Benson and Mike can't or won't say to one another. Why did you decide to seek out those images and actually print them on the page?

Bryan: I pitched it to my editor, and she pitched it to the design team. I took about 300 photos, put them in a file on my computer, and winnowed it down. Part of the conceit was that there are those moments when Ben feels as though he should say something, or that though there’s a gap he should fill with dialogue, and Mike will feel the same. They do that by sending one another photos of where they are and what they're seeing, hoping that it'll impart something that the language they have isn't able to. I'm a fan of fiction that has photos in the text, and you don't really see it that often. I thought it would be cool to try my hand at that.

ESQ: As you winnowed them down, what made an image worth keeping, and what made one go in the trash? What were you looking for?

BW: I was looking for a feeling. Part of it was self-selecting in that Benson and Mike are seldom in the same place over the course of the novel. Geographically speaking, there are certain things they wouldn't be able to experience simultaneously, so that determined who could send what and when they could send it. But also the presence of other folks in the background, the clearness of a sky, the familiarity that one character may have with a building or a gas station or a restaurant, the amount of blank space in a photo, really trying to take stock of everything that was actually in the image and overlaying that with how Benson and Mike felt at the moment they sent it… that was one equation that I used to decide who sent what and when.

ESQ: Speaking of places, this is your second book set in Houston. The love you feel for the city is evident in gorgeous lines like, "Spring in Houston is scalding sidewalks and sun-drunk love bugs." What makes Houston such a special city for you, and such a renewable source of creative power?

BW: I think the diversity of the city is the easy answer, but it doesn't make it less true in that it's such a vibrant city. You have so many communities who've made a life here, and they've done that while making a life among other communities, in tandem with them. It’s a really singular culture. I feel very lucky to get to tell stories about the place. But also, there’s a warmth I’ve experienced in the city. I think a goal of mine for both Houston and Osaka was to take that warmth, to take the generosity that I've been privy to, and to put that on the page as an entity in the narrative itself that the characters experience, but also one that exists as a standalone entity.

ESQ: How did you come to fall for Osaka?

BW: I started visiting about five years ago. I'd go once or twice a year because, if you don't mind an 84-hour layover in Taipei, you can get a quite cheap ticket from Houston. I would go just to visit friends and hang out. Once I started writing the novel, I became a bit more conscious about talking to folks, doing research while I was there, and bringing that research back to imbue into the text. I ended up editing the second to last draft of the book in Osaka for most of last summer, which now seems really wild. I'm grateful that I got the chance to do that, because there were some details that I wanted to make as accurate as possible. I wanted to do right by whatever iteration of the city I was putting on the page.

ESQ: Both Memorial and Lot are incredible character journeys, but they're also compelling stories about cities and how they change over time. Is that somewhere your interest lies, in telling the story of a city as well as a group of characters?

BW: Absolutely. Largely because one of the lovely things about telling a story about a city is that you'll never get it right. The city itself is singular for everybody who occupies it, and everyone's experience is valid and simultaneously true. It really opens up the narrative world, so to speak, as far as what you're able to accomplish on the page, and the different lengths you're able to stretch toward with your characters.

ESQ: On some level, when you tell a story in a city, you can't get it wrong. You can say, "This is my city. This is how I see it."

BW: You can't get it wrong! No one can call bullshit. That doesn’t negate the wealth of research you've got to do in order to develop the comfort and familiarity to write about a place. But, simultaneously, you can do it knowing in the back of your head that, as long as you're doing your due diligence, the iteration of the city going on the page is going to be true in itself.

ESQ: The backbone of this novel is the joy of food and the intimacy of cooking. Why was it important to you to have food be such a strong and vibrant presence in this story?

BW: I think the primary answer is that I enjoy reading about food, so I wanted to write a book that had a lot of food in it. But the more structural answer returns to that idea of the silences implicit in conversations. As each character tries to impart comfort and pleasure and a feeling of just being okay, not only to themselves, but to the folks around them, cooking and sharing a meal was one vehicle through which to do that.

It was important to me to have culinary arcs and culinary trajectories for Ben, Mike, and Mitsuko. Plotting that out was a major part of the drafting process for me, because I wanted every character to have a reason for why they were cooking or what they were cooking, or how they were feeling when they were eating it, or what love languages worked through food.

ESQ: When you say you plotted an arc or trajectory, what did that look like? Did you have a separate culinary outline?

BW: The book went through eleven drafts. Once I was about halfway through the drafting process, I started charting out exactly who was cooking what, when they were cooking it in linear time, and what that looked like in relation to what everyone else was cooking in that same linear time. I really tried to match up those timelines to have a clear sense of each character’s respective arc. For Benson, he's amazed at the act of cracking an egg at the beginning of the narrative, but by the end, he's cooking in tandem with Mike. Trying to figure out what his trajectory would look like, having it make sense both structurally and emotionally, was important to me.

Whereas with Mike, he's someone with a culinary background, but his arc was one of figuring out how to be more emotionally available, and how to intuit what people need or what will comfort them. Mitsuko is the one character who is constantly trying to comfort others. To see how each of them was cooking, what they were cooking, and why they were cooking it—to see it all in relation to one another was important to me. But at the same time, if a reader went through the book and they didn't notice any of that, that'd be quite all right. Sometimes a sandwich is just a sandwich.

ESQ: You mention Mitsuko using food as an act of care. This novel highlights how food can be a language of love and care. Has that been your experience of cooking and eating?

BW: Yes. Very much so, though when I was growing up, I wouldn't have been able to articulate it as such. My parents had a pretty diverse set of friends, so we were constantly privy to a litany of cuisines, both in our home and in the homes of our neighbors and the folks that we held dear. I've really been fortunate to have been exposed to a lot of different cuisines from the very outset. Sharing a meal with someone or cooking for someone—there's a level of thoughtfulness that has to go into it. You’re hoping that on the other side of it, you're able to impart some feeling to the person you’re feeding. Really being thoughtful about that on the page was important, because I just think it's something that's important to me in life.

ESQ: You've written about food in an essayistic capacity. What do you bring from nonfiction food writing to fiction?

BW: The primary structural answer is just what the act of cooking looks like. I try to take the directives given in a cookbook and imbue them into whatever narrative I'm writing in a way that isn't obvious or simplistic. If I have a character cook something, then the overwhelming majority of the time, I'm going to try to cook it myself so that I have a sense of what their physical space and movements will look like. Is it something they're able to cook while thinking about other things? Can they cook it and have a conversation with the people surrounding them? Getting a clear sense of the technical portion of the act of cooking is something that I'm able to pull from nonfiction, but also the context and history of a dish. Reading authors like Eric Kim and Elazar Sontag, who really are able to imbue their narratives with emotionality while simultaneously giving an abundance of context, has really been helpful in my own narratives.

ESQ: Did you have any cooking disasters in the process of researching dishes for this novel?

BW: All the time. Memorial was an exercise in failure, in a lot of ways. Mitsuko is an infinitely better cook than I am. There are a number of dishes I tried where what would have taken thirty minutes to an hour became a week-long thing, with me in a corner wondering, "Do I have to take that scene out if I can't cook it?" It was a lot of trial and error.

ESQ: What's your favorite thing you cooked in the process of writing Memorial?

BW: Potato croquettes, which is a dish that's really important to Mike over the course of the text, by way of its importance to Benson and Mitsuko. But also a rolled omelet. When I started the book, my rolled omelets were just ghastly, and now they're halfway decent. So if nothing else good comes from Memorial, I've gotten better at that.

ESQ: The role of cooking in Memorial gets me thinking about the role of domesticity. In your work, you create such richness and detail in domestic life. What do you find so fruitful about this facet of life that other writers might pass off as narratively uninteresting?

BW: I think in a lot of ways, domesticity and mundanity are life. One of the challenges of this novel was to write a story where the overwhelming majority of relationships aren't characterized by the capital letter moments, like, "We’re partners now," or, "I’ve changed how I feel about you.” Rather, I wanted to write about the build-up to those moments, and the creases and plateaus in between. I wanted to know what that kind of book would look like, because it struck me that perhaps such a book wouldn't have an antagonist, other than life itself. That was really enticing to me. It was something that I wanted to read.

ESQ: Something else I loved about Memorial was your representation of an HIV-positive character, which was so impactful and so beautifully explored. As you wrote this book, why was it important to you to represent someone with a positive status? What were the things you did to tell that story the right way or the faithful way, as you see it?

BW: This might just be a failure of my reading, but I haven't read a narrative in contemporary American literary fiction where there was a Black cis male who was pos where the narrative wasn't reductive or demeaning, or where it wasn't failing to do right by the character. Your status is such a large component of gay life. Among Black men who have sex with men in this country, we are well on track for one out of every two of us to have HIV over the course of our lifetimes. In the South, in particular, it's an epidemic, and it has been for some time. From the standpoint of context, it wasn't something that came from far left field. It’s a conversation that is actively being had, depending on who you’re in conversation with.

But what was really important to me for Benson and for every character, in a lot of ways, was even if they were navigating trauma, to not have that trauma and the difficulty of the situations in which they found themselves constitute the entirety of their narrative. It’s important to me that Benson is pos, but he is also someone who has loves and fears and hopes, and he laughs and he has things that he wants to eat. Sometimes he gets a little sick of other people; sometimes he wants to have people around. Telling a story in which all of the characters are able to feel many different things simultaneously was deeply, deeply important to me.

ESQ: This novel is deeply concerned with the idea of home. At one point, Mike warns Tan, "You shouldn't make a home out of other people." Having completed this novel, where have you arrived on the meaning of home?

BW: I think in a lot of ways, I wrote the book because I wasn't sure from the outset how each of them conceived of home. I wanted to explore what home meant for every single one of these characters. I wanted to write a book in which home could be elastic, and home could be different for each one of them, but also a book where it could change for each one of them over the course of the narrative. The last word of the book is "home"—that was a late-stage edit from my editor that I’m super grateful for. Mitsuko is finally going home, and yet, it's her getting there, not necessarily Benson or Mike. Writing this book was me trying to figure out an answer to that question without really expecting to find an answer, so much as problematizing the question itself.

You Might Also Like