Big Ears Festival preview: Planting the seeds

The 2023 Big Ears Festival is celebrating what its intrepid producer and crew have been able to build over the span of 10 seasons, 10 Tennessee springtimes that have established a new national planting ritual.

At Big Ears, the seeds of every culture in America’s quilt-like garden are entrusted again to the richest red clay on Earth, not just to see what comes up, but to nurture it, to protect, water, and weed it, to anticipate, admire, and harvest it, because the cycle is our sustenance. What we plant in Knoxville every spring sustains our unique past, our challenging present, and the future no one knows.

One seed planted at Big Ears, perhaps the most important one, is the seed of connection between artists and the children who are the only hope for the arts.

Our expressive arts have a life of their own, and they’re watching us. Like everything else we consume, the arts don’t happen by accident. They depend on us to sow their seeds in a way and in a place that encourages germination and growth.

The way we encounter and experience the arts is personal. It's unique to each individual. I saw this fact in action last week.

I’ve been a gardener for decades. And I’ve been a parent for almost a decade. Last Friday, in a pre-Big Ears Festival event, those roles intertwined in a way that I really hadn’t expected. The soulful artist Lonnie Holley opened an intimate exhibit of his work at the University of Tennessee Downtown Art Gallery, 106 S. Gay St., Knoxville, and I took my kids.

It was the day that started with alarming weather forecasts which came true at lunchtime. Our school superintendent issued an emergency message at 1 p.m. that sent parents scrambling to pick up their kids early. For weeks I had talked to my little ones about meeting Lonnie Holley, but around 2 p.m., it looked like we were on the front edge of a tornado, and driving Downtown seemed out of the question.

Then the heavy weather passed. By 4:30 pm, the sky was completely clear and warm, so we headed south on Clinton Highway.

When we parked by the Southern Railway Depot, the wind blew us across the bridge over the train tracks and right in the door at the Gallery on the first block of Gay Street. And before I could finish a quick hello to Big Ears producer Ashley Capps, my kids immediately surrounded Lonnie Holley, peppering him with questions about his scrap steel sculpture that rocked when they touched it.

For almost an hour, Sam and J.D. and Patti Job were completely engaged with one of the most formidable artists in America, a man whose life story will haunt them when they are old enough to comprehend its horrors. In this golden hour, in this safe, beautiful space, with Lonnie’s voice singing softly in the background on the Gallery’s stereo, the four of them delighted in each other’s company, oblivious to everyone else, free to dream and draw and make things for each other.

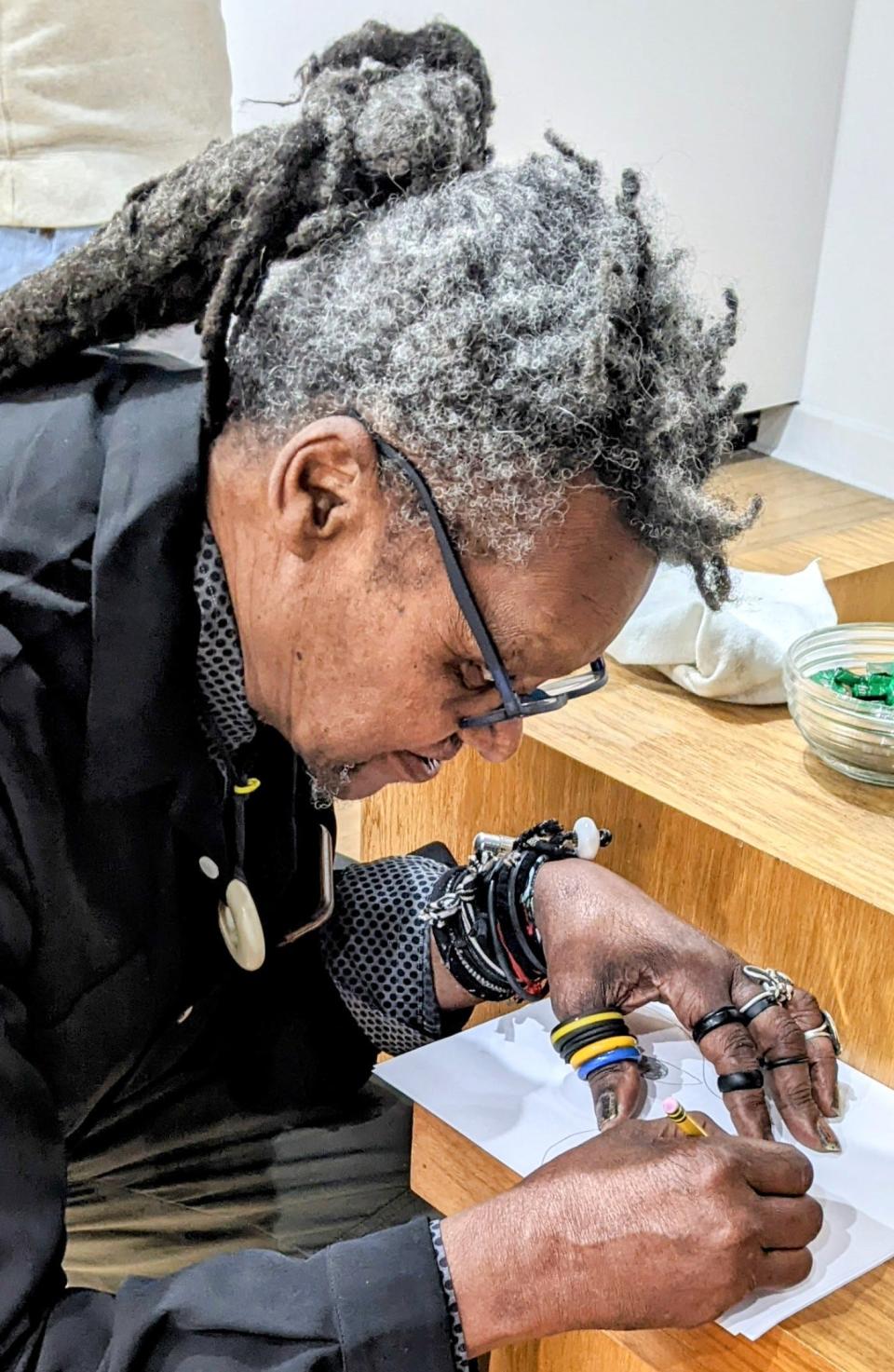

My children studied every inch and every component of his sculpture. They stared at his framed paintings, at his amazing dreads, at the deeply etched contours of his face, and at his hands, heavily jeweled with rings and bracelets for protection from sharp edges on the material he picks up along roadsides to rechristen as art. They hung on every word he said, and they weren’t the least bit shy about responding.

Well, Patti was shy at first. But then she disappeared for about five minutes, long enough for me to search the entire space for her, before she emerged from a curtained area in the back of the gallery with a piece of copier paper on which she had drawn a heavily jeweled hand to match Lonnie’s. When she gave it to him, his compliments didn’t make her giggle or blush. She just smiled the smile of gratitude you never expect to see on a 5-year-old’s face.

J.D., whose favorite artists are named Peterson and Audubon, drew several birds for Lonnie, who then drew a swan on his smartphone with a stylus, and the swan morphed into a multi-colored face in profile. Sam folded a couple of paper airplanes for Lonnie, and Lonnie folded one for Sam. Sam’s planes looked like experimental Skunk Works stealth fighters, and Lonnie’s was decidedly simpler, but his bore the artist’s signature on the right aileron, making it a collectable work of art.

His signature lets anyone know that the fingers that creased the blank paper for a simple glider have raised entire worlds of art from the sandstone and mud, the trash and debris of life in hardscrabble Alabama. Lonnie’s paper airplane also spoke volumes about his victory over the force of “progress,” which almost wiped out his world when the airport in Birmingham doubled in size decades ago. When he launched his paper airplane for Sam, I could see it all flooding back, because for Lonnie, art is an acronym for “all rendered truth.”

Lonnie then drew a face in profile for each of my children to take home with them, black pencil on white paper, one of which was distinctly reminiscent of Pablo Picasso and two of which were Paul Klee-like faces within faces. They are signed and dated, and in a few days they’ll be ready to be picked up from the frame shop.

There’s nothing in life more enjoyable than watching your children experiencing something beautiful that they’ll never forget. A close second goes to dinner at Señor Taco on North Broadway right after meeting Lonnie and watching your kids fill about 50 sheets of paper with more pencil drawings, tinted with every color from the salsa bar, sticky with queso and guacamole. And for the rest of the weekend, my little artists never asked to watch their tablets.

I want to encourage everyone to check the Big Ears Festival website and find out where you can find Lonnie in Knoxville the last week of March. You need to see his creations, hear his voice, and feel the spirit that emanates from him.

Plant the seeds, on the edge of what.

“I remember an old lady say/Watch what you’re digging because/you first need to plant/for something to really grow./She told me take care of yourself, my child/be careful as you go life’s way.” _ Lonnie sings in “Cold Day.”

It’s time for Big Ears. Springtime in Tennessee. Plant the seeds.

John Job is a longtime Oak Ridge resident and frequent contributor to The Oak Ridger.

This article originally appeared on Oakridger: Planting the seeds