Being Color Blind Doesn't Make You Not Racist—In Fact, It Can Mean the Opposite

The idea of a color blind society, while well intentioned, leaves people without the language to discuss race and examine their own bias.

Color blindness relies on the concept that race-based differences don't matter, and ignores the realities of systemic racism.

Below, OprahMag writer Samantha Vincenty talks to sociologists Eduardo Bonilla-Silva and Meghan Burke about the problem with color blindness—and how to become anti-racist, instead.

The international protests over the deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery have just begun to spark positive change, pressuring states from Minnesota to California to rethink how they'll fund law enforcement and address police brutality in the future. The long-overdue outcry over the ways Black Americans have been mistreated, underserved, and underpaid has also effectively strong-armed many non-Black people into having tough conversations about race and racial inequality in the U.S.—often, for the very first time in their lives.

Unfortunately, however, I can say firsthand that some people still really don't want to talk about it. At all. They'll be the first to tell you they don't have a racist bone in their body, and they don't care if you're white, black, purple, or blue, etc. In fact, they say, they're "color blind"—meaning, they don't even see race. And that refusal to see it often goes hand-in-hand with an urgent desire to stop discussing racial disparities as soon as possible.

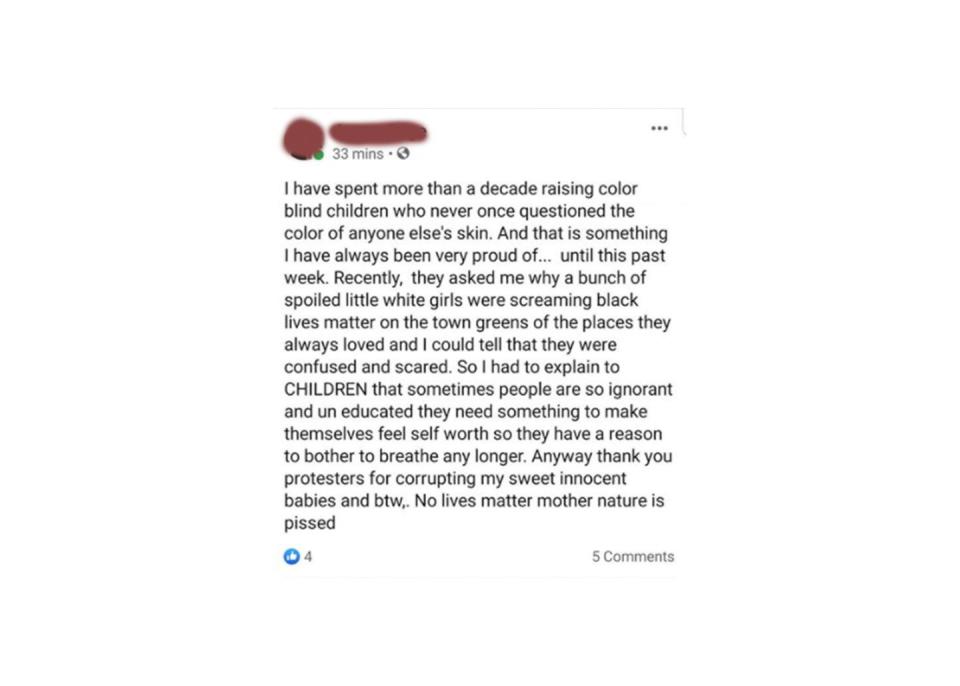

The current Facebook debates amongst my 40-something, overwhelmingly-white former classmates in the Connecticut suburb that I lived in as a teen are, to put it mildly, a roiling cesspool of feelings. Insults are hurled, former crushes de-friended. One woman's patient explanation of how the "redlining" housing policies of the 1930s have had lasting effects on economic inequality is rebuffed with angry insistences that the concept of white privilege is actually "reverse racism."

And then one day, to my pleasant surprise, I saw an article about how 1,100 people in my old hometown gathered for a Black Lives Matter rally on the town green. This peaceful show of support caused several longtime white male residents to absolutely lose their minds...at least online.

The ignorance in some of my former classmates' posts didn't shock me; as a white Latinx woman who doesn't "look Puerto Rican," plenty of people felt safe making ugly remarks in my company throughout the five years I lived there. What did surprise me was how quickly those who identified as color blind became panicked—or even furious—when their neighbors started wondering whether racism had been living in their own backyards (and town greens) this whole time.

To better understand how color blindness connects to bias—and counter-intuitively helps to uphold racism instead of rendering it powerless—I spoke to two people who literally wrote the book on the subject: Sociologists Eduardo Bonilla-Silva, author of Racism without Racists, and Meghan Burke, author of Colorblind Racism.

The concept of color blindness flourished after the civil rights movement.

"I'm not the first one to say this, but for many white folks, being labeled racist is among their worst fears," Burke says. "And as we're continuing to learn in this country, for many people of color, Black folks in particular, their greatest fear is not surviving an interaction with a police officer. So we're really talking about very different worlds of experience."

Burke says the roots of color blind racism were largely well-intentioned. "It borrows right from that last third of Martin Luther King Jr.'s speech, where he says that he wants people to see his kids for the content of their character, not the color of their skin. So I think it's easy for a lot of well-meaning white folks to hear that and say, 'Well, gosh, okay. Yeah. I don't want that to be the primary lens that I use to judge people's character."

In order to understand how colorblindness winds up denying the lived experiences of other people, Burke continues, "it's also important to get clarity about what is meant by 'racism,' and some of the unintended harm that a colorblind framework can cause." To do that first requires a basic understanding of how Americans, and particularly white Americans, think about racism, and the big way sociologists believe that's evolved over the past 150 years.

From the late 1800s to the mid 1960s, the system of racial segregation and oppression known as Jim Crow made it illegal for Black Americans to have the same social and economic rights as white Americans. When we see photos of the Black students who comprised the Little Rock Nine face down hoards of angry white people just to go to school, no one debates what that is: Blatant hate. “The practices of domination were in your face. The ideology was overt,” says Bonilla-Silva. After the civil rights movement of the 1960s brought some positive change, he says, those who weren’t directly impacted in the years that followed (such as those in suburban white communities) could easily choose to believe that America’s big, ugly racist period was a thing of the past.

Pointing to 40 years of data, Bonilla-Silva says that racism instead became embedded in what he calls "now you see it, now you don’t-type practices" that are harder to call out—which, conveniently, makes it tougher to pin them squarely on discrimination. Bonilla-Silva uses the example of a realtor who’s been told they can’t talk about race. If a person of color such as himself tells that realtor, “Hey, I want to live in a mixed neighborhood," the response might be, "Hey, don’t talk about that! I don’t see race, we’re all humans.” Instead, “we 'steer' people into different neighborhoods—a Black neighborhood, a Latino neighborhood, a white neighborhood. So you don't need to talk about race to produce racialized outcomes.”

"Not seeing" race denies systemic racism.

As everyone is steered into unofficially-segregated parts of a city or town, it can be easy for those in white-majority communities to never think about the laws, zoning, and social policies that promote gaps in education and wealth equality along racial lines—particularly if they’re only interacting with those who look like them, and who share similar world views. Burke says the wish to believe that everybody has an equal shot at success is deeply tied to our collective American belief in "individualism," or the habit or principle of being independent and self-reliant. In the individualist way of thinking, problems like poverty and health problems are cast as personal moral failings that can be overcome, not symptoms of a larger broken system.

"If you do the right thing, you'll be successful. If you don't, it's your fault," is how Burke describes that logic. "But then that usually gets into the land of what, I emphasize, are often-imagined cultural differences: 'It's because of people's culture that X, Y, or Z happens.'"

Burke's description echoes what I've been seeing from certain white classmates on my timeline: clumsily vocalized beliefs that people who live in areas with elevated crime rates and lack of access to supermarkets must not mind it that much, or else they'd work harder to move somewhere nicer—such as my classmate's own neighborhood, for example. If someone believes they've solely earned every success in their life through hard work, considering the advantages that may have greased their path upsets that long-held self belief in their own merits. "In the so-called race of life, if one group begins 50 yards ahead, members of that group are more likely to win," says Bonilla-Silva.

Individualist thinking also often blames anti-Black violence, such as police brutality, on a villainous person—such as Derek Chauvin, the police officer who murdered George Floyd. "In that way of thinking, the bigger problem is the bad actor," Bonilla-Silva says. "And yes, there are bad actors and bad cops. But as a system, racism doesn’t depend on bad people to remain in place."

He also asserts that even police violence enacted by Black law enforcement, such as the officers arrested for tasing two Atlanta college students during a May protest, doesn't mean the racial politics of police brutality aren't real. "Systemic racism can be enacted and performed by Black bodies and brown bodies," says Bonilla-Silva.

So how can people move away from color blind thinking?

If you're someone who was raised to "not see color," and you'd like to become actively anti-racist instead, first accept that a major shift in thinking won't happen overnight. One objective is to move away from thinking of racism solely as views and acts committed at the individual level, and instead a system of moving parts. Burke says that ongoing self-examination is crucial, and so is believing others' painful life experiences instead of minimizing them to maintain your comfort. "I still honor this process. Trying to do this self interrogation to really think about how I could do better," says Burke. "And I think we have to listen to the voices of Black folks, other people of color, and other marginalized folks broadly in all of our spaces."

You can also dive into the wealth of great podcasts and books about race in America. (Realizing that I don't read enough work by Black authors has been part of my own recent self-examination.) Resist the urge to ask a Black person in your life to explain things, or worse, expect them to soothe any guilt you may be feeling. I recently heard one anti-racism advocate recommended buddying up with a fellow non-Black friend, keeping a text thread for sharing questions and resources to educate each other.

What if you're already on board with doing the work, but want to win your frustrating Facebook "friends" over? (Ahem.) That typically requires a big time investment, Burke says, with a varying payoff. "When I was on it, I tried to thoughtfully engage in the right moment with the right person, with the right issue to say, 'Let's unpack this a little bit.' And sometimes people would say that that was effective for them. But boy, it takes time."

In other words, you need to have ongoing Facebook conversations, not just one. "There's no perfect post, no one answer. It has to be two people who are really having a conversation. And even then, it's what people do after that conversation that matters."

"Every time that someone says, 'I'm color blind,' you have to tell them, "okay, so you have a racially integrated life? You live in a mixed neighborhood? And then they may say, 'well, my neighborhood is...it's just a regular neighborhood,' says Bonilla-Silva. 'You mean white then, again?' And then they just get totally discombobulated, cannot articulate the word. Yeah. And then you keep pressing yet to show that their colorblindness is just a set of rules—because in truth, their lifestyle is often totally white neighborhoods, friends, and associations."

As for me, I'll continue to pipe up on Facebook, in what I now refer to as "the Hometown Dialogues." But talking with Bonilla-Silva and Burke has made me think my limited free time is best spent on more direct action and self-education instead. After all, I was raised to be color blind too, and discarding that way of thinking means continually engaging with Black people and Black culture in highly imperfect ways. I can't do that part for other white people. I can only help us fumble forward together.

"It's like we can't get out of our own way," Burke says. "It's similar to what Robin D'Angelo has talked about in her book, White Fragility. It all becomes this thing where the comforts and the privileges of white folks get protected—instead of Black lives."

For more stories like this, sign up for our newsletter.

You Might Also Like