The Ballad of Ron and Dorinda

Around the nursing home where she lives, in Phoenix, Dorinda Lopez, seventy-one, mostly keeps to herself. People can tell she’s from somewhere else, on account of her southern accent. When she gets angry, as she sometimes does when she talks about the past, it gets thick. The word “aggravate gets like ten syllables.”

Only Lisa, who lives across the hall, has heard the whole story. But Lisa is forgetful. She recently complimented Dorinda on her pretty nightgown.

“Lisa, you gave it to me!”

“Oh, I did?”

Lisa is not a risk to spread gossip.

Abby knows the story, too. Dorinda tells it to her in fragments, before bedtime. But Abby is a cat. She’s not talking, either. Abby is a lot like Dorinda in that she likes to escape; when the door is open, Abby slips out and Dorinda calls for her kitty to come back, the best she can do from her wheelchair. “The only people who know me now,” Dorinda told me, “are people who know me now.”

Dorinda was one half of the most romantic jailbreak in American history, and for a long time no one in her life but Lisa and Abby knew it. But then, this spring, Dorinda’s telephone rang, and she answered it. The man who broke her out, Ronald J. McIntosh, looked increasingly likely to get out of prison himself. Now that the story might finally have an ending, she was ready to tell it from the beginning.

“I bet you’re gonna ask me a lot of questions no one’s ever asked me before,” she said to me before launching into her tall tale. Dorinda knew one thing for sure: “Being with Ron was the best ten days of my life.”

Samantha Dorinda Malone Fiegler McPherson Lopez was an only child from Cobb County, Georgia. Her many names marked the winding path that led her to a bus seat in shackles, riding through the California night in 1982. She had done six months at a state penitentiary in Georgia. Now she was headed for a fifty-year sentence in federal prison, which she assumed meant black-and-white uniforms, watchtowers, guards with machine guns. She had hoped to go to West Virginia, but her lawyer told her that Pleasanton, just east of Oakland, was where women with a rap sheet like hers ended up.

By the time she was twenty-one, Dorinda had three children and had been married for five years to “the biggest jerk that ever walked the planet.” The marriage failed, and she wed another man, divorced him after a few months, and then married a third, collecting new surnames along the way.

Dorinda was attractive, though prosecutors would later insist that she wasn’t as irresistible to prisoners and guards as she boasted. She resembled a southern Angela Lansbury with curves, and she had a talent for attracting men—and for bending them to her will.

In 1970, Dorinda repeatedly persuaded a store manager not to prosecute her for shoplifting, and when the five-and-dime decided enough was enough, she beat the charges—and then sued for malicious prosecution, winning a $2,500 settlement. Dorinda moved on to forgery, writing bad checks. She had an affair with her married attorney, and he got her released early from state prison. On parole, Dorinda wrote more bad checks, and when police began looking for her, she disappeared. She sometimes called the Cobb County sheriff’s office to taunt them.

In 1981, she convinced her husband, Carl Lopez, and three other young men to rob banks with her. The joints were nasty affairs: Posing as an IRS employee, she’d call a small-town bank and obtain the manager’s home address. Her confederates would then burst into the house early in the morning and hold his family hostage while he emptied the vault.

Such was the sway Dorinda held over the men that Tony Wade, one of her accomplices, couldn’t help but express his affection for her at trial.

“Yes, I love her, too, very much,” Wade said.

“Would you lie for Mrs. Lopez?” asked prosecutor Bill Adams.

“If it came to it, yes.”

Was she manipulative? “I think that would be an understatement,” Adams told me. “Her life story is that’s what she does. She talks people into doing things.”

And so at thirty-two years old, with three kids back in Georgia and an estranged husband now in prison himself, Dorinda bounced in her seat as the bus entered the prison gates. There was a full moon. Buildings loomed ahead. The grass was so green that in the moonlight it turned blue.

In the morning, Dorinda climbed out of her bunk bed, looked out the window, and rubbed her eyes. “You have got to be kidding,” she muttered.

Inmates carried boom boxes playing soul and rock music. Buildings were covered in fresh redwood. She heard the hollow pop of tennis balls and the clatter of Nautilus weights. There were racquetball courts, soda machines, pool tables, regular china in the dining hall, air-conditioned private rooms, a TV and stereo in each unit, and copies of Time and Life, Pleasanton’s prisoner-edited newspaper. Inmates wore their own clothing: blue jeans, dresses, skirts. The thirty-foot fence was lined with long rows of pansies and snapdragons, and the golden hills beyond turned emerald green when the rains came.

The biggest shock was the people. A perk of Pleasanton in 1982 was that it was coed. Men and women walked around holding hands. “It was like Shangri-la,” Dorinda said. “If you were gonna be in prison in the eighties, Pleasanton was the place to be.”

Dorinda had wandered into the middle of a national experiment in coed prisons. Pleasanton had opened a decade earlier with a $6.5 million price tag and had high operating costs, but prison psychologists crowed about the near-total elimination of gangs, rape, and “homosexual pressure.” By the early 1980s, there were three federal and at least thirteen state prisons emulating the concept.

Sex wasn’t initially on Dorinda’s mind. “I was missing my children and thinking about how stupid I had been,” she said. She took a job in the kitchen because she wanted to work so hard and get so tired that she could sleep at night. She washed dishes for twenty-one cents an hour.

During one of her first shifts, Dorinda was working in the kitchen when a naked couple, mid-thrust, fell through the ceiling and landed on the food manager’s desk. The pair had finally worn out a soft section of the kitchen’s popular roof.

America’s prison population was soaring, thanks to rising crime rates and harsh drug laws. At some prisons, overcrowding meant gymnasiums filled with triple bunk beds, gangs, and violence. Pleasanton, with its hormonal, college-campus atmosphere, had earned the nickname Club Fed. Sex was in the air—and everywhere else. Guards found prisoners making love in broom closets and crawl spaces. Inmates cut holes in the crotches of their jeans, stood at the far end of the jogging track, and talked very close. Other times, couples openly rutted against walls while friends “pinned” for them, prison slang for watching out for guards.

Dorinda had a few “walkies,” slang for boyfriends, since walking around holding hands was the only sanctioned physical contact. But they were always casual. “It wasn’t ‘go up on the roof’ serious,” she said.

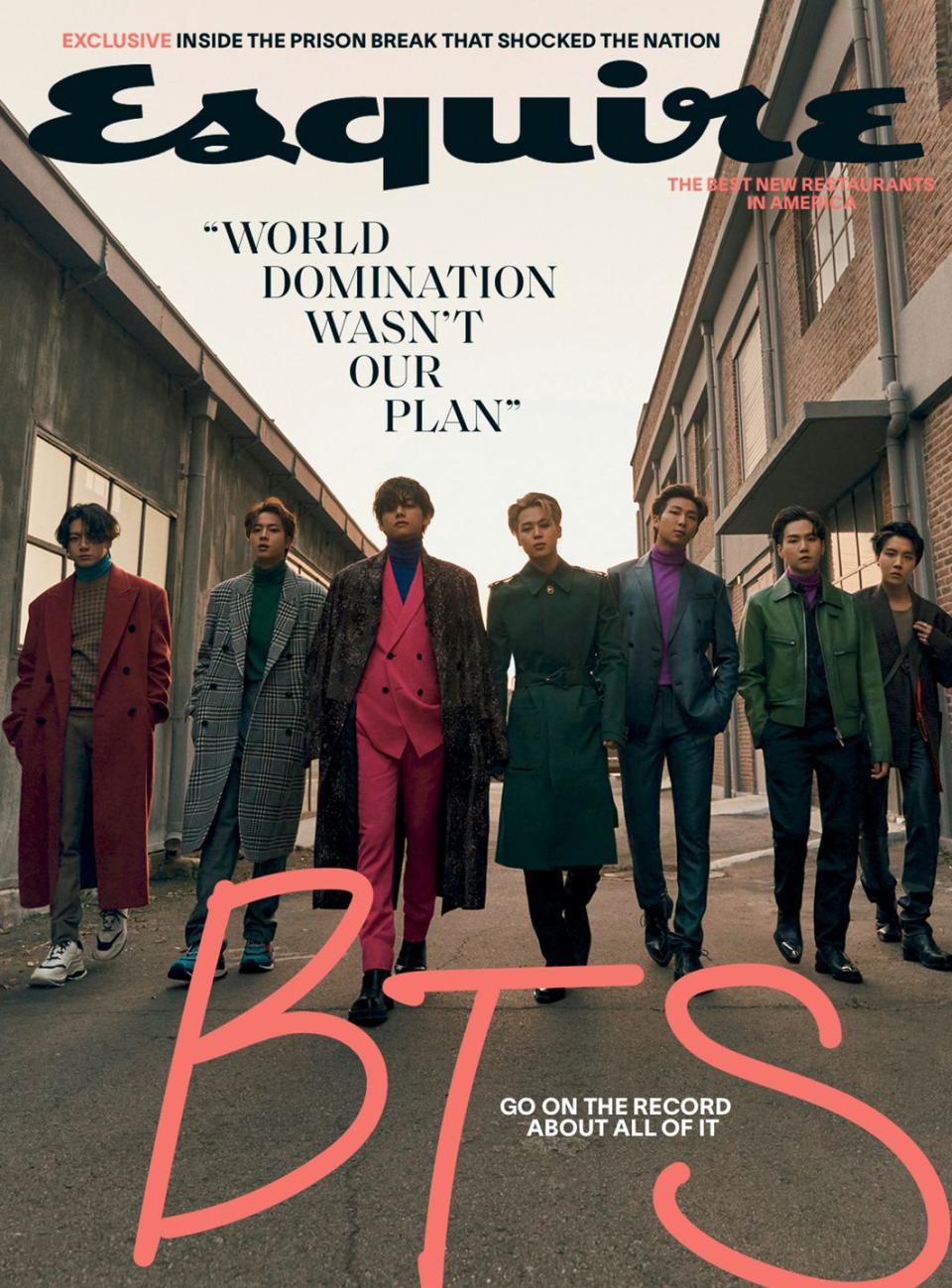

This article appears in the Winter 2020/21 issue of Esquire.

subscribe

Dorinda also took younger women under her wing. They called her Mama, including Shelley Bosch, an eighteen-year-old from Alaska who was serving a 104-year sentence for her role in a murder. She’d fallen in with two boys and helped distract a sixty-three-year-old widow before the younger boy clubbed her to death. Dorinda met Bosch in the choir room. “She had these huge brown eyes,” Dorinda said. “My heart just stopped beating. I said this little prayer in my heart. She looked about thirteen.”

After eighteen months, Dorinda took a job in the business office doing clerical work and was soon promoted to accounting clerk. She wore a three-piece suit to work. She became head of the Inmate Council, taking minor prisoner grievances to the warden. Life settled into a comfortable-enough routine. “If you have to be in prison, Dorinda,” she told herself, “this is the place to be.”

In December 1985, a new inmate arrived in the office looking for a job. He was forty-one, from Seattle, and big, weighing more than two hundred pounds. He had the steady, reliable face of a mailman. He told Dorinda he had some financial experience. In fact, Ron had plenty.

It was the 1980s, and white-collar criminals like Ron were filling up minimum-security prisons. They served short stints for securities fraud, embezzlement, and tax evasion. (Michael Milken, the so-called junk-bond king, would serve time at Pleasanton a few years after Ron and Dorinda.)

At the office, Ron sat beside her. He tracked accounts receivable, and she maintained the institutional records. He was at Dorinda’s desk all day, asking endless questions, sometimes the most obvious stuff. “We just had the dumbest man on earth working here,” she told him finally. “You’re either coming in second or you’re trying to know me. If that’s the case, we can talk after work.”

Their first date was a movie. Dorinda had seen it before, and she began to nod off. “I put my head on his shoulder and my leg on his leg,” she said. “I was embarrassed that I had done that, but Ron said later that it showed I trusted him.” Two weeks later, friends pinned for Ron and Dorinda while they kissed for the first time.

All winter and early spring, their relationship blossomed. They saw movies together. At church, they prayed together. They went to dances together. Ron didn’t say much about his background, but it was clear that if Dorinda had moved the world according to her whims, Ron’s life had been a series of failed attempts to get what he wanted.

In the late 1960s, Ron married a woman he’d known for two weeks to avoid the Vietnam War, but he was drafted anyway. He trained in helicopters, hoping the war would end before his schooling was complete. He was shipped to Vietnam. He trained as a mechanic, calculating that their survival rate was higher than that of pilots. Ron flew in dangerous sorties anyway, landed on the corpses of fellow soldiers, heard their bones crunch under his helicopter’s skids.

Ron was awarded a Bronze Star, was promoted to warrant officer, and commanded eighty-six mechanics and thirteen helicopters. He’d found purpose in the military. But when he returned home, he didn’t have enough college credits to get a commission. He bounced around: minimum-wage work in a JCPenney warehouse, a stint at a friend’s carpet-cleaning company. He was angry at the men who had avoided the war and were further ahead in their careers. He had a wife and two kids, but his marriage began to falter.

Ron was a quick study of financial markets and found work in commodities. In a panic to make up for lost time, he embezzled $130,000 from clients at his Seattle brokerage. He was sentenced to eighteen months. In prison, he met another broker, Michael Anthony, and when they got out, they created First International Trading Co., a precious-metals futures business. The pair swindled twenty-five hundred investors out of $18 million. In 1985, he was sent back to prison for a parole violation, then pleaded guilty to the metals scam.

Whenever Ron shared these details with Dorinda, it was obliquely. He once mentioned another case that was pending against him, and he’d make occasional phone calls, but he mostly gave the impression of wanting to leave the past in the past. Besides, his current stay would be a short one: He was scheduled for release in February 1988.

Ron was porky and lovable, and Dorinda called him “Teddy Bear.” He nicknamed her “My Lady Bear” and “Mrs. Bear.” Ron was protective, too. One time, a male friend patted Dorinda’s butt. Ron picked him up and threw him against a wall. “They’re gonna need to find a way to say hello without tappin’ your ass,” he told her later.

Ron would do anything for her, Dorinda realized.

In April 1986, Shelley Bosch, Dorinda’s friend from choir, appealed her sentence and was denied. She was twenty-one, with another 101 years in prison stretching before her. Unable to imagine staying there for the rest of her life, Bosch and two other inmates cut holes in two fences and slipped out.

The community surrounding Club Fed was shocked, and it pressured the warden, Rob Roberts, to increase security. A few weeks later, Dorinda watched workmen ring the prison with barbed wire and install a new alarm system. They also planted trees to try to prevent an airborne escape.

Other things were changing at Pleasanton. There had been roughly three hundred inmates when Dorinda arrived, four years earlier. Now there were more than six hundred. Overcrowding meant fewer perks. Cosmetics shipments were banned. There weren’t enough laundry machines. The Inmate Council disbanded itself in frustration. Prison was starting to feel more like prison.

In spite of later denials that any of this occurred, here’s what Dorinda claimed—insisted—happened next: She began to notice discrepancies in the office ledgers. Money seemed to be missing. She suspected prison officials were embezzling it. Dorinda asked for a meeting with Roberts, a stern Army veteran turned prison warden.

“I’ve been keeping the books,” she said. “I know where all the kickbacks went.”

Roberts studied her, then asked, “How much longer do you have?”

“I’m up for parole in 1991.”

“Do you expect to be alive then?”

“I do.”

The warden smiled. “Accidents happen every day.”

That night, Dorinda returned to her room after dinner and found it trashed, she later testified. Her clothes were in a pile and doused with shampoo, baby powder, and coffee grounds.

A few weeks later, she claimed, a guard knocked her down while she was in her room. “If you don’t stop making waves, you’re going to drown,” she said he told her. She claimed another guard gave her a box of razor blades and intimated that she should kill herself, and that a third left a can of Coke in her room with shards of glass in it. In September, he threatened her with a switchblade, waving it in her face and pushing her to the ground.

“You see how accidents happen?” he said. “We’ll have to try harder next time.”

Dorinda confided in some inmates, but no one heard more details than Ron. Throughout the summer of 1986, she shared her fears with him in the rec yard, at the dining hall, at movie night, and in the office. They were both in danger, she warned him, because of the malfeasance she had uncovered.

It all seemed to burden Ron profoundly. His mood changed; he became emotional and withdrawn. If someone dropped a Coke can or bounced a basketball too close, he’d jump. He had nightmares. In late August 1986, Ron went to the prison dispensary and got a prescription for Ativan.

In September, the Bureau of Prisons informed Ron that they would soon transfer him to Lompoc, an unfenced work camp near Santa Barbara, something he’d requested in advance of parole. Dorinda was distraught. She told Ron about new threats. As his transfer approached, he broke out in sweats. His hands shook.

Dorinda told me she was beside herself with worry about what awaited her when Ron was gone and he could no longer protect her. The night before he left, he pulled her aside.

“Be out on that field every day,” he said. “In my mind, I’ll know that you’re safe.” He was adamant about the timing—10:45 to 11:30 a.m.—and exact about the location. It confused her, but she promised him she’d be there.

On the morning of October 28, 1986, Ron came into the business office. Dorinda hid in the bathroom—she was too emotional to see him—while he collected his eleven dollars in pocket money and a Greyhound bus ticket. He was a white-collar criminal, rated a one out of seven on the flight-risk scale, with no history of violence and only a year left on his sentence. He would be allowed to take the bus by himself to Santa Barbara and report to Camp Lompoc for the remainder of his time.

That morning, Dorinda sat in the grassy field for forty-five minutes, just as Ron had requested. She looked out at the thirty-foot fence and the barbed wire beyond it. That night, she cried listening to “The Last Farewell” by Roger Whittaker and “The Sweetest Thing (I’ve Ever Known)” by Juice Newton. She turned the radio off. The songs reminded her too much of Ron.

The next morning, Dorinda reported for work at the business office. Marty Feipel, a supervisor she was friendly with, pulled her aside. “Dorinda,” he said, “guess who didn’t go to Lompoc?”

A week later, Fred Holbrick, a real-estate developer, arrived at San Jose International Airport for a morning helicopter tour. He told Pete Szabo, the young Australian helicopter pilot, that he was developing a tract of land in the East Bay. He did not tell Szabo that the aircraft was the same type that he had flown in Vietnam. Nor did he tell him his real name: Ron McIntosh.

Most escapees are caught because they go home, or because they run out of money, or both. But before going into prison, Ron had purchased a house on five acres in Oregon. He owned a forty-nine-foot oceangoing yacht named the Wanda docked north of Seattle, and that spring he had arranged, from prison, for it to be repaired. The summer before his escape, he’d made sixty-eight phone calls to a friend who had rented him an apartment outside Sacramento. He had a Chevy Blazer. He had three phony IDs.

Most important, Ron may have had money—a lot of it. The government had never recovered more than $1.7 million that had gone missing. If he indeed had access to that cash, he could run forever.

Ron was on the U. S. Marshals’ wanted list, but he was a low priority. In 1985, twenty-five prisoners had made similar escapes on furlough. There was no nationwide manhunt for this white-collar fraudster. With the cash, the yacht, the IDs, and the car, he could go anywhere.

Ron and Szabo lifted off from San Jose International Airport and headed north. The pilot flew along I-680 toward Las Trampas. Ron asked if they could get closer to the ridgeline. Szabo worked the pedals and joystick to maneuver closer. Then he saw a flash in the corner of his eye.

“Set it down,” Ron said. He pointed a handgun at him.

Szabo landed on a remote hillside. Ron waved him out of the helicopter and demanded his shoes. Szabo nervously smoked a cigarette in his socks as Ron kept the gun trained on him. Ron checked his watch. After ten minutes, the hijacker closed the cockpit door and lifted off. As his helicopter whirred above him, Szabo took a few steps toward the road and felt a sting in his foot. The ground was covered in white bull thistle, and Ron had taken his shoes. It took Szabo forty minutes to mince his way to the nearest house. When the homeowner opened the door and saw a shoeless man jabbering about a stolen helicopter, he slammed the door in his face.

With Ron no longer at Pleasanton, Dorinda withdrew into herself. “I probably didn’t say twenty words outside of work while he was gone,” she said. “I’d find me a very quiet place on the compound and just cry.” She stopped wearing blouses and pants, a style she was known for, and started showing up for work in sweatpants. Dorinda kept her lunchtime vigil for a week. She sat in the grass crying and praying.

On the morning of Wednesday, November 5, Dorinda trekked out to the field, just as Ron had requested.

She saw a helicopter on the horizon. That was normal enough—there were small airports all around the East Bay. But this one was coming in low. It circled the prison once. Inmates began shouting as it descended and then hovered inches from the ground. Dorinda squinted.

“It’s Ron,” she said aloud.

She walked, then ran toward the helicopter. All around the yard, inmates cheered. Ron pushed open the door. “Do you want to get out of here?” he shouted over the rotors.

“You’re driving!” she shouted back.

The escape was an immediate media sensation. daring helicopter prison breakout, read the front-page story in the San Francisco Examiner. Szabo flew with an ABC News crew along the route he’d flown with Ron before being hijacked, his feet still sore from the thistles. At federal prisons around America, wardens strung up quarter-inch steel wires—so-called chopper-stoppers—to thwart copycat escapes.

A manhunt was on, but within a few days, the trail had grown cold. With no investigative leads, the press feasted on tips and rumors. Ron had wired money to Panama and buried gold coins. He had broken Dorinda out because she spoke Spanish—she didn’t—and could help him escape to South America. Ron had a connection in the British West Indies and might flee there. Ron’s attorney, L. Stephen Turer, speculated that his client might have broken out because he was worried about future criminal charges, which he left vague. When a reporter asked if Ron might contact him, Turer replied: “In a foreign language, maybe.”

Dorinda was sure they were going to clip a tree branch. She looked out the window as Ron descended into a meadow surrounded by trees and bushes. They landed with a gentle bump. There was a truck waiting.

“Where are we going?” she asked as they got on the highway.

“Sacramento,” he said. “What do you want to eat?”

“Kentucky Fried Chicken.”

They bought a fifteen-piece bucket of the Colonel’s Original Recipe and then arrived at the apartment outside Sacramento, full of adrenaline. They were already peeling off their clothes as they entered the apartment.

“When did you plan all this?” Dorinda wanted to know.

“I’ve got you here, by myself, in an apartment, with a bedroom, and you wanna talk about that?”

They made love for the first time—on the bed, the couch, the floor. They didn’t have to listen for a guard’s key or kiss with their eyes open. They ate the fried chicken, then he gave her a bubble bath. “When he kissed me,” Dorinda said, “it was thoroughly, from the top of my head to the bottom of my toes.”

The magnitude of their escape hit the next morning when Dorinda turned on the TV. The morning news shows were covering the jailbreak. “Good God,” she cried. “Ron, we’re national!”

They played house in the modest one-bedroom apartment. They ate out. They took drives, just because they could. They made love. In the morning, they read The Sacramento Bee with coffee, her legs draped over his. The newspaper had dug up their past misdeeds. They shot each other skeptical glances over the pages. “Really?” they took turns asking. “Did you do that?”

Dorinda tried to figure Ron out. “He was always there but not there,” she said. “There were things going on in his mind that I couldn’t get to.” She wondered, years later, with tears in her eyes, “What kind of man goes and throws away his life to help someone escape?”

On Monday night, five days after the helicopter ride, Dorinda put on a wig, and together she and Ron went to the jewelry store at a nearby mall. Two platinum wedding rings in the case caught Dorinda’s eye.

“I want you to have that,” Ron said.

“We don’t need that.”

“I want you to have that.”

Ron put down a $1,000 cash deposit. He told the clerk it was their twentieth wedding anniversary. He had them engraved with t.b. love m.l.b. and m.l.b. love t.b.—for their nicknames Teddy Bear and My Lady Bear.

Ron suggested sailing away on his yacht and escaping to South America. Dorinda refused, still hoping to somehow reunite with her three children. “In retrospect, we should’ve,” she told me.

This article appears in the Winter 2020/21 issue of Esquire.

subscribe

When Ron and Dorinda went back to the mall to pick up their wedding rings, Dorinda immediately sensed something was amiss. “All these young, earnest men in blue suits,” she suddenly realized. “I could spot an FBI agent from five hundred yards.”

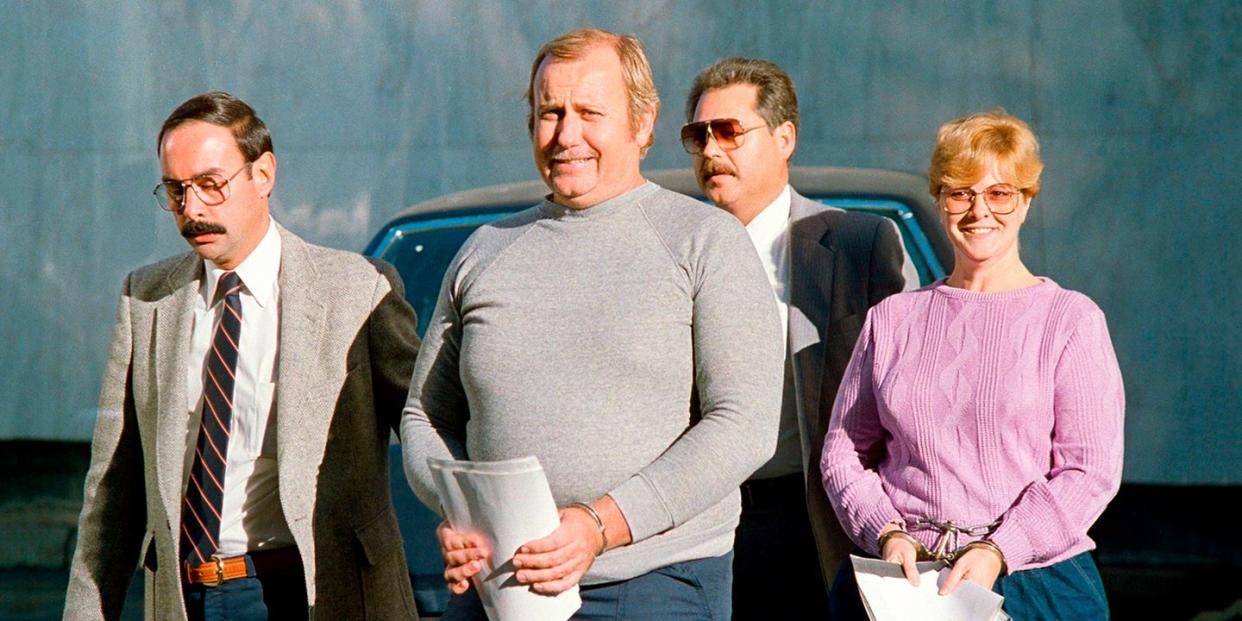

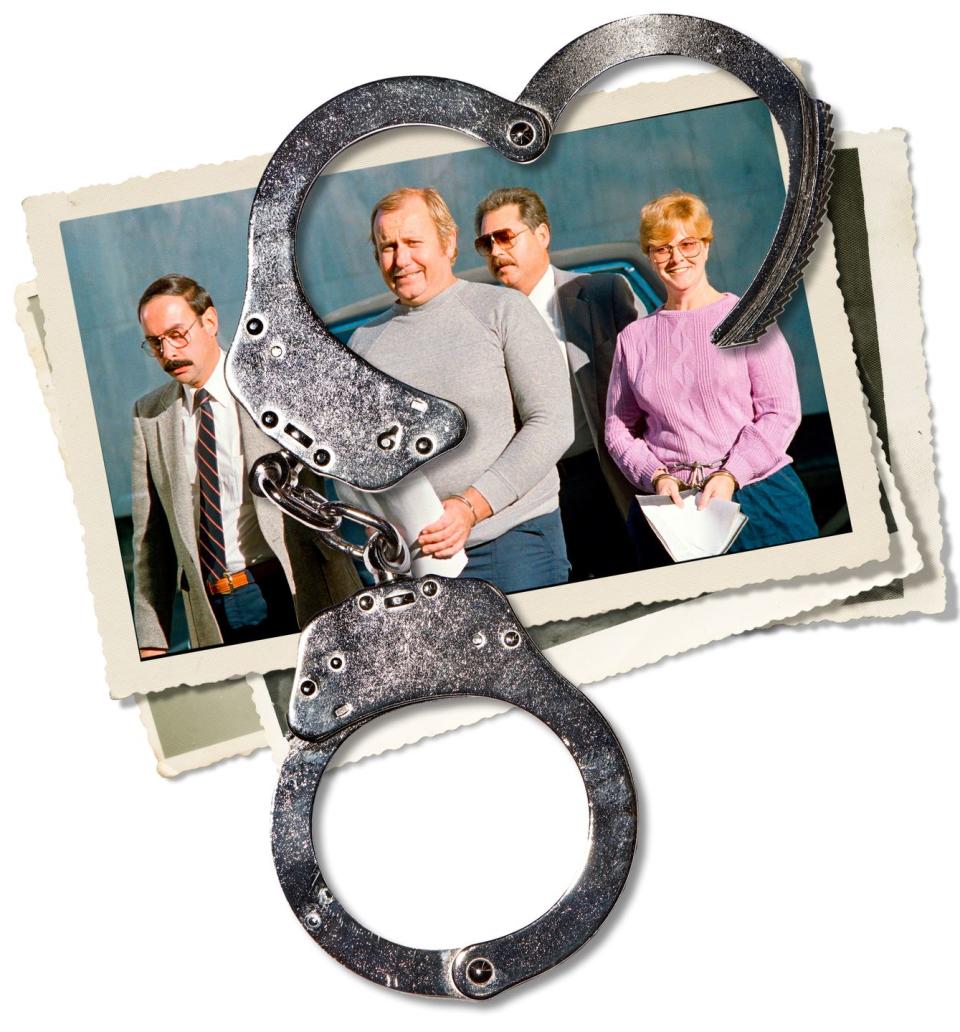

She considered running but instead stood there and held her breath. “Put your hands in the air,” a voice said from behind. It was a U. S. Marshal.

Ron had paid the balance on the rings with a check—with the same alias he had used to brush up on his flying skills before the escape. Plainclothes police officers and U. S. Marshals had been staking out the store since the day before.

The federal agents, some toting shotguns, arrested Ron and Dorinda and seized Ron’s briefcase. Inside, they found a loaded .357 Magnum handgun with hollow-point bullets and $1,180 in cash. In the car, they found another handgun, a CB radio, a police scanner, and binoculars.

Outside the mall, Marshals pushed them into separate cruisers. As he pulled away, Ron leaned out his window and shouted, “I love you!”

It was the greatest romance and the greatest rescue I’d ever heard of, told to me over the phone by Dorinda on successive Wednesdays in the spring and summer of 2020. I became intrigued and then obsessed. She salted her retelling of the escape with small confidences, admitting previous lies here and there. But I longed to believe her every word.

Unsure if I could, I called up Mark Zanides, the man who prosecuted her case back in 1987, and recounted everything she’d told me. I asked about the corruption she alleged at Pleasanton, the threats she claimed to have endured, and Ron’s scheme to break her out. Zanides listened patiently but then asked me, “Why?” He repeated it slowly, as if speaking to a child. “Why do you think this was his idea?

“She’s obviously touched you, David,” he said. “She’s reached out and touched you. Your heartstrings are throbbing. She’s soft-spoken. She’s got that Georgia accent.”

It was true. As weeks had turned into months, Dorinda had been asking me for small favors without my really noticing. I found her daughter’s Facebook page for her. I tracked down her grandson’s phone number. We discussed ways to convince her children to speak to her again.

When I did favors for her, she was effusive. “Oh, I think I’m in love,” she texted once. She called to compliment my interview style. I repeated her compliments to friends over dinner. But doubts crept in. Zanides’s words echoed in my head: “Remember, she’s a con man,” he’d warned me. “That’s what they do. She wouldn’t be playing you, would she, Dave?”

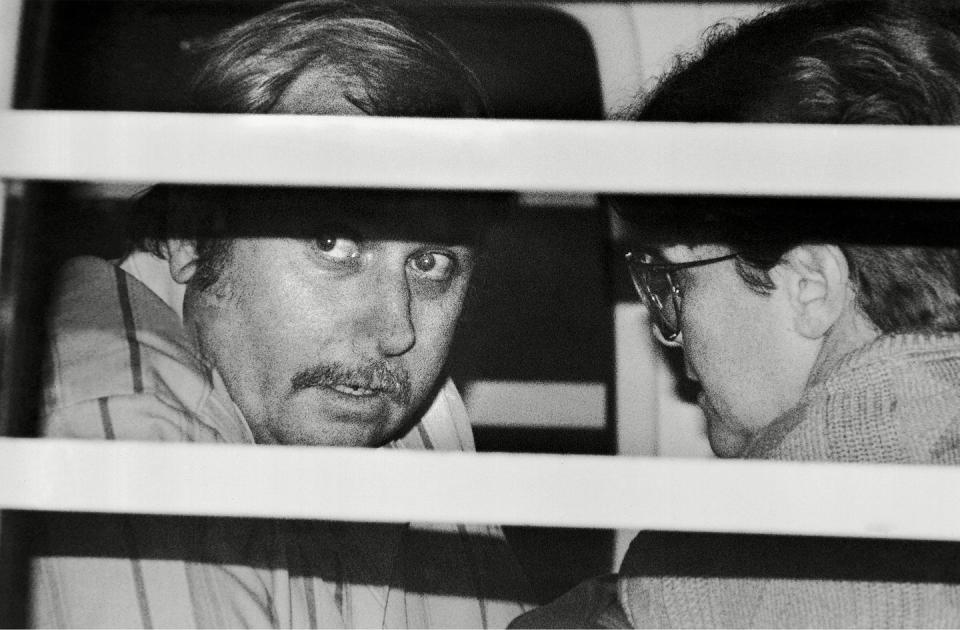

The couple’s joint trial began in May 1987. Ron’s lawyer, Judd Iversen, drew a portrait of him as a haunted Vietnam veteran, a man susceptible to being played. Two psychiatrists recounted Ron’s wartime heroics and diagnosed him with post-traumatic stress disorder. Ron had failed ninth-grade math. He read eighty words a minute. He had a 101 IQ. He was overweight. Ron had been used by his country and now used by this woman.

The press helped Iversen’s case. The Sacramento Bee played up class differences between them in side-by-side profiles. Ron was middle-class, a veteran, “Mr. Suburbanite,” and finally “a lovestruck puppy” under Dorinda’s spell. She was a twice-divorced southern jezebel. Even Ron himself wasn’t so sure. “It is possible that I was misled by her,” he conceded to a psychiatrist before the trial. “But I don’t believe that’s the case.” (Ron, through his current lawyer, David Shapiro, declined to talk to me for this story.)

A necessity defense—that Ron was forced to break Dorinda out in order to save her from corrupt guards—was their only hope. “Now, this isn’t exactly the story of Camelot,” Iversen told a courtroom packed with reporters. “But it is the story of a cavalryman who rescued his lady.” In court, Dorinda sat with her foot hooked around Ron’s leg.

Iversen refused to let Ron on the stand. He’d been Ron’s criminal-defense lawyer for years, and there was another looming charge related to his days selling gold coins. Dorinda was confused and ticked off when she learned he wouldn’t testify and corroborate her story.

She could have used it as her case fell apart. At trial, Dorinda insisted that she had no advance warning of the helicopter escape. And yet there were signs she’d known he was coming all along. From the day Ron jumped furlough until 6:02 on the morning Dorinda flew away, someone from her housing unit had made nine telephone calls to the same number Ron had been phoning all summer as he prepped the escape. A guard testified that she sprinted to the helicopter and took off in no more than fifteen seconds. She had started wearing sweats the week Ron was on the lam—better than jeans and a blouse for jumping into a hovering helicopter.

Dorinda implicated the warden and a slew of guards and prison employees in embezzlement, cover-ups, and threats. All of them denied it. Logbooks showed many were off duty on the days she claimed they’d threatened her.

Then there was Joyce Bailey Mattox, another inmate at Pleasanton with an interesting rap sheet.

“Do you know Joyce Mattox?” asked Zanides.

“Yes, I do,” Dorinda said.

“She used to call you Mom, didn’t she?”

“A lot of people call me Mom.”

Mattox was serving a forty-year sentence—for hijacking a helicopter and breaking her boyfriend and two other men out of a South Carolina state prison in 1985. Although I tried to talk to her for this story, I was never able to find her.

“She used to hold court and show off her press clippings,” Dorinda testified. “And yes, I was there when she did that.”

In prison, Dorinda was overheard boasting, “Well, it would be really easy to do it here at Pleasanton.”

On May 19, 1987, the jury retired for deliberations. Geoffrey Hansen, her defense attorney, barely had time to get a cup of coffee. “I went down as the guy with the fastest guilty verdict in the history of our office,” he said.

Before the sentencing hearing, Ron, Dorinda, and their attorneys descended to the basement of the federal courthouse in San Francisco. “Judd was a Universal Life minister, or whatever you could get through the mail,” said Hansen. “I was the witness.”

The bride wore a gray jumpsuit, as did the groom.

A few minutes later, the judge sentenced Dorinda to five years in prison for the escape. Ron got five years as well, plus twenty years for air piracy. The man who’d had fifteen months left on his sentence, the man who could have disappeared into the California countryside after jumping furlough, had earned a quarter century in prison for going back for his lover.

And then, four days after their wedding, a jarring headline appeared on the front page of The Sacramento Bee. Detectives were ready to file a new criminal charge.

A teddy bear and dependable dope Ronald J. McIntosh was not. He’d been fooling Dorinda, prosecutors, jurors, and the press all along. If she had conned Ron, it now appeared that Ron had conned her right back.

LOVEBIRD TARGET OF SLAYING PROBE, the Bee headline read, MCINTOSH SUSPECT IN 1984 KILLING.

From the maximum-security unit at Marianna, in Florida, Dorinda followed along as best she could. She was stunned by the allegations.

In 1983, Ron had been walked out of Lompoc, the minimum-security work camp, where he’d been serving an eighteen-month sentence for wire fraud. He and his new prison buddy, Michael Anthony, needed capital for a precious-metals scheme they had cooked up, and they borrowed some from a fellow con man, Ronald Ewing. When they didn’t pay him back, Ewing threatened to expose their scam, and Ron and Anthony paid an ex-con $50,000 to murder him. The hit was supposed to be a “Houdini”—with Ewing decapitated and his body burned beyond recognition. The hitman shot him, but then he panicked and fled. Ewing’s partially disrobed body was found in the surf at Montara Beach a day later.

Homicide detectives questioned Ron in connection with the killing. But they didn’t have enough evidence to press charges. In November 1985, Ron arrived at Pleasanton to serve time for a parole violation and then the metals fraud.

In the summer of 1986, when he was making all those calls from Pleasanton, he was still being investigated for the murder, and he knew it. In June, he put in for a transfer, perhaps hoping for a furlough and a chance to escape before the investigation advanced further. His anxiety, the sweats, the Ativan prescription—were those about Dorinda’s fears or his?

Perhaps a little of both. When Dorinda began complaining about threats, it complicated Ron’s plans. After jumping furlough, he might have gotten away—if not for his going back with a helicopter.

After Ron was charged with murder, Dorinda stayed loyal to him. “I didn’t think he was guilty then, and I don’t think he’s guilty now,” she told me. “Ron wouldn’t do that. I would do that.” She felt somehow responsible. “I wish I’d walked away and stayed away from him.”

Dorinda began signing legal letters with the name “Mrs. Dorinda Lopez-McIntosh.” Because they had married, they were allowed to write each other letters and work on a book. (It never happened.) They also made illegal phone calls to each other. Dorinda would call Ron’s mother in Seattle, and then she would set up a three-way party line. He proposed another escape plan—a commandeered deputy sheriff’s car, a kidnapped state judge—but she was done running.

She alternated between pitying him and lashing out. “Ron McIntosh is stupid,” she told a friend, struggling to entertain the possibility that the man she married was capable of such violent acts. “Prison made him lose his mind.”

In December 1990, Ron was convicted of murder and given a life sentence. Ron and Dorinda never spoke again.

Dorinda set about doing her time. There were joys along the way. She busied herself with choir practice, religious services, and work in UNICOR, the federal prison-labor program. Bosch, her “daughter” who escaped from Pleasanton, was recaptured, and they were reunited in Florida. They became even closer. Dorinda pushed her around in a wheelchair when she was diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis. When Dorinda had back problems, Bosch pushed her around.

“We were quite a pair,” Bosch said.

Dorinda converted to Catholicism and befriended Sister Anne Marie Raftery, a cheery Irish-born nun. Raftery relished hearing Dorinda’s story, even as she cast some doubt on Dorinda’s version of events. “She claims she didn’t know he was coming,” Raftery told me, and laughed. “Went to see what was going on with the helicopter. All I can say is ‘Hmm, what a coincidence.’ ”

Ron, meanwhile, was moving deeper into the federal system. In 1999, he tipped off prison officials that a fellow inmate had bragged about several unsolved murders. Ron testified, but he was not rewarded with a reduced sentence, as he’d hoped. In 2001, he entered the Witness Security Program and was moved to a special prison unit.

Dorinda flirted with guards and had new boyfriends. But she couldn’t help thinking about Ron. She asked Gary McDaniel, a private investigator in West Palm Beach who had taken up Ron’s appeal, to pass along love notes. McDaniel told her that Ron had lost his wedding ring in prison. Dorinda was furious. She threw hers out a window.

Dorinda’s health began to fail. She was moved to a medical unit in Texas, and then in 2010, she was paroled on compassionate release. She had spent three decades in prison, minus ten days. Cut off by her estranged children and with few friends, Dorinda moved to an assisted-living facility in Arizona. She liked the dry heat. The desert was a good spot for disappearing. From her apartment window, Dorinda could see mountains. She hung up two photos: her grandmother and Bosch, who was released in 2016. Dorinda adopted Abby and told her stories about Ron at night before bed.

On a Friday morning in March 2020, Dorinda found herself in a new kind of lockdown, this one imposed by COVID-19, and she decided to answer my telephone call.

I didn’t know it at first, but she was in touch with someone else, too: Ron. They had returned to their habit of passing each other messages through Gary McDaniel, the private eye. Ron was advancing a new appeal, one that his lawyer was confident had a real chance of success. The prospect of his freedom created a mess of emotions.

Sometimes Dorinda was adamant that she didn’t want to see him. “I know he’s gotten older, too, but I don’t want him to see me in a wheelchair,” she said. “Men get older. Women look older.” Other times she insisted she just wanted closure. Perhaps a phone call to reminisce and say a proper goodbye.

But by May, they were getting chippy. “We are having words,” she said. “He told me to move on with my life. ‘We had good memories. And we need to move on.’ ”

I thought it had meant something to Dorinda that I believe her version of events: that the escape was necessary to save her from threatening guards, that she had never manipulated Ron. Above all that, “it was a rescue,” she said. “That’s what I want people to understand. It was a rescue.”

I came to realize that the prosecutor Mark Zanides wasn’t quite right about my relationship with Dorinda. She wasn’t trying to con me. She wasn’t even trying to convince me. She was trying to convince herself. She and Ron had destroyed their lives for ten days in a Sacramento bedroom. It was a rescue—it had to be.

That’s the promise of love: a rescue. Someone spots you, trapped, alone, and in danger. He scoops you up, carries you from one life to another. Once you’re in the cockpit, only some are brave enough to ask the question “Who are you?”

Ron had failed her. He’d hidden the truth of himself: his pending murder charge. He’d carelessly used a checking account to buy wedding rings. He’d screwed up, and she’d lost good years. “You see, my problem was I trusted Ron, and I think that trust was misplaced,” she said. “I had a right not to get caught. I had a right to stay free, but I couldn’t.”

Dorinda doesn’t live in a wheelchair in the Arizona desert. Not really. She’s still up in the air. The engine roars. Her heart races. The prison gets flat in the distance. And a stranger flies her in circles to nowhere.

You Might Also Like