Babylonian tablet from 3,000 years ago could be 'oldest-ever fake news'

An ancient Babylonian tablet telling the story of Noah and the Ark could be the oldest-ever example of “fake news”, a Cambridge researcher has claimed.

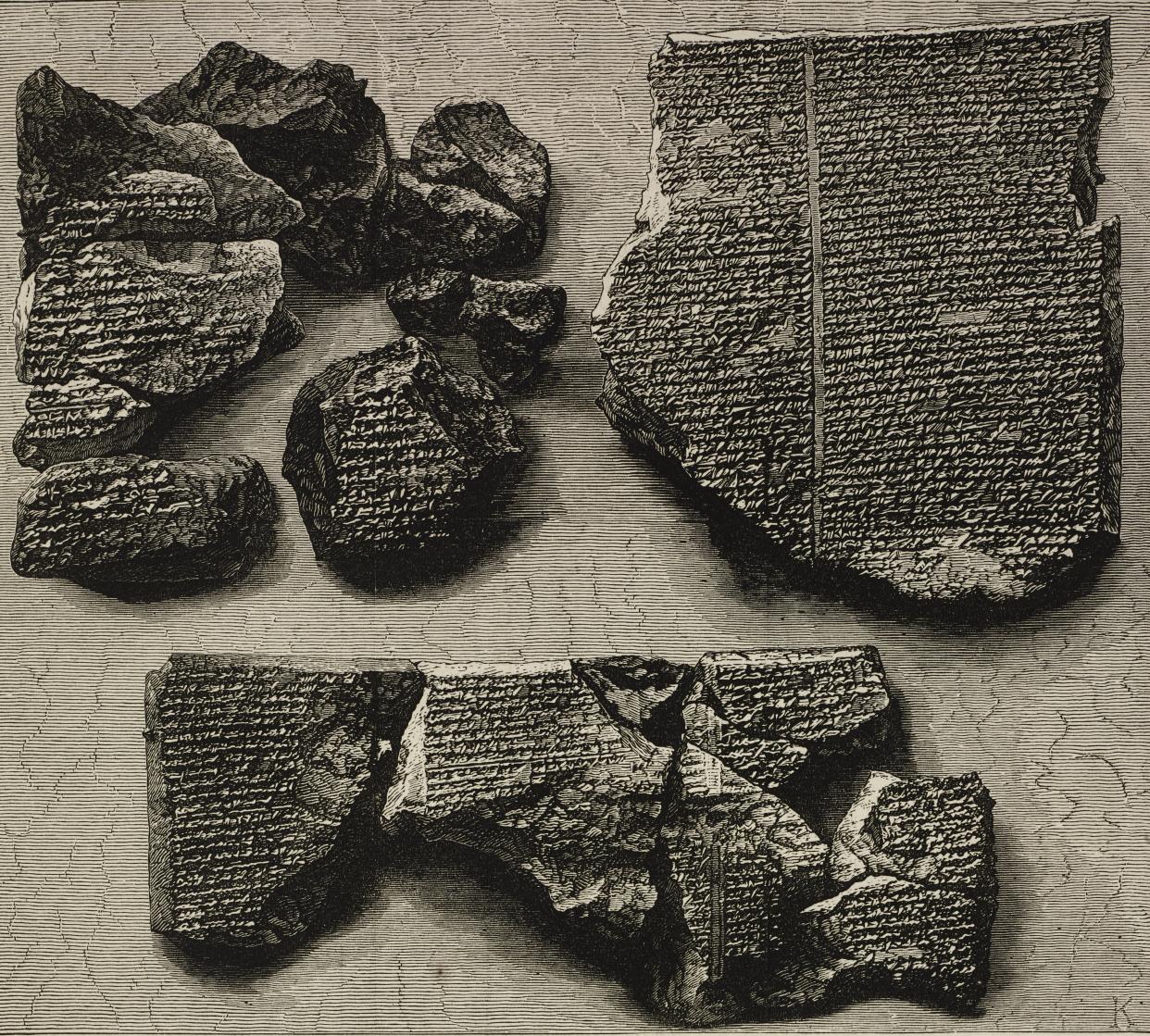

The deceptive words were found on the 11th tablet of Gilgamesh, dating to 700BC, according to Dr Martin Worthington from the University of Cambridge.

In an interview with the Telegraph, he revealed how the words show how the Gods lied to mortal men (part of a Babylonian belief that Gods needed to be fed by mortal men).

The tablet was found in 1872, and tells a different version of the Noah story, where the god Ea appears in the skies, suggesting that “food will rain from the skies” if they build the ark.

READ MORE

Binary Earth-sized planets possible around distant stars

Insects could die out in ‘worst extinction since the dinosaurs’

NASA satellite captures incredible beauty of UK seen from space

Why Iran’s nuclear escalation goes unchallenged

Dr Worthington told The Telegraph: “Ea tricks humanity by spreading fake news. He tells the Babylonian Noah, known as Uta–napishti, to promise his people that food will rain from the sky if they help him build the ark.

“Once the Ark is built, Uta–napishti and his family clamber aboard and survive with a menagerie of animals. Everyone else drowns.

“With this early episode, set in mythological time, the manipulation of information and language has begun. It may be the earliest ever example of fake news.”

Babylon was an important city in ancient Mesopotamia, located in Iraq about 60 miles south of Baghdad.

The civilisation was highly advanced, with Babylonian astronomers using geometry to track the planets as early as 350BC.

“No one expected this,” said Mathieu Ossendrijver, a professor of history of ancient science at Humboldt University in Berlin, noting that the methods delineated in the tablets were so advanced that they foreshadowed the development of calculus.

This kind of understanding of the connection between velocity, time and distance was thought to have emerged only around 1350 AD.

The methods were similar to those employed by 14th century scholars at University of Oxford's Merton College, Professor Ossendrijver said.