When Asian Elders Felt Unsafe Walking Alone, These Volunteers Stepped Up

“I have to go at three,” August Wood tells me at the start of our interview. “I have to go meet the ladies. It’s hard to express how delightful these women are.”

Wood, a 52-year-old communications professional, volunteers twice a week with Compassion in Oakland, a free service that pairs Asian elders with chaperones who can walk them safely to their destinations. After we finished speaking, Wood took a 20-minute bus ride from her Oakland apartment to escort a group of friends from the Rose of Sharon assisted living facility on their weekly walk around Lake Merritt.

The friends, who are all immigrants from Asia, had been making the 3.4-mile loop for years. But given the spate of violence against Asian elders around the country, and especially within San Francisco's Bay Area, they haven’t felt safe walking alone this past year.

“I get to walk with these ladies who are so charming. But the reality is, I’m only there because they’re scared. People in their community are being targeted. They don’t know if they can leave the house,” Wood says.

Since last March, the United States has seen a sharp rise in attacks against members of the AAPI community. Data collected by the group Stop AAPI Hate revealed more than 2,800 firsthand accounts of anti-Asian acts across the U.S. between March 2020 and February 2021. Of that set, 9% were physical assaults, and 7% involved victims over the age of 60.

Compassion in Oakland—which now has over 1,000 volunteers—was originally formed in February 2021 as one man’s response to these attacks. Jacob Azevedo, 26, was shocked by the statistics, and by the gruesome stories of Asian elders being harmed in his native Bay Area.

In January, an 84-year-old Thai immigrant died in San Francisco after he was pushed to the pavement by a man who suddenly approached him. A February video shows a 91-year-old Asian American man shoved to the ground in Oakland’s Chinatown; police said his assailant went on to attack two other Asian Americans— a 60-year-old man and a 55-year-old woman, that same day. Bloomberg reports that Oakland’s Chinatown saw 18 attacks against Asian Americans in two weeks in February.

That same month, Azevedo offered to walk as a chaperone with a post on his Instagram account, which garnered 20,000 likes, hundreds of offers to help in the comments, and an interview on ABC News. "Help us make our elderly community here in Oakland feel a little safer to walk down the street!!" Jacob said on the post. Azevedo selected Compassion in Oakland's first cohort of volunteers from emails that landed in his inbox; more offers came from a GoFundMe fundraiser, inspired by his initial Instagram post, with proceeds going to purchase hand alarms for the elderly.

“Jacob has the biggest heart. He was so tired of hearing of these attacks. He said, ‘I’m not a big buff guy. But I’ll walk with you,'” Katrina Ramos, Compassion in Oakland’s co-founder, tells Oprah Daily. Ramos reached out to Azevedo after seeing his post, as did fellow co-founder Jess Owyoung, a full-time college counselor; all three took on leadership positions within the rapidly growing organization.

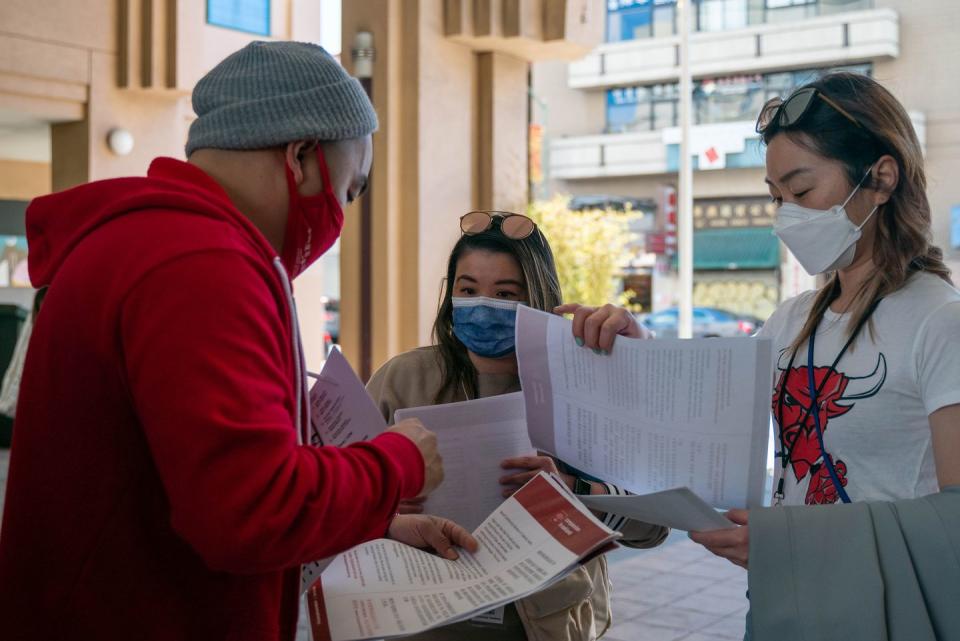

Compassion in Oakland now offers two services. During weekend patrol shifts, “pods” of three or four volunteers travel an area of 16 square blocks, spreading the word about their service via flyers as well as speaking to shop owners. The volunteers always include a speaker fluent in Mandarin or Cantonese, two widely spoken Chinese dialects. The volunteers range in age, race, and ethnic backgrounds. Then, during the week, Compassion in Oakland also offers a hotline so that volunteers can meet elders at a specific location, and a pre-planned time, and walk them to their destinations.

One of the early volunteers, Amy Wong, recalls that at first, people were hesitant to accept the group’s help. “Now that the trust has been built, people are approaching us. The response has gone from nothing to a cascade of requests,” Wong says, referring to calls placed for chaperone services during the week. The group's founders estimate that it reaches hundreds of elders a month.

On walks, volunteers—especially those who speak Cantonese, the predominant language spoken among the area’s Asian elders—hear stories that describe an atmosphere of fear. One weekend, Owyoung met a group of women who first turned down Compassion in Oakland’s services, but then returned to the volunteers to ask for help because they were scared walking back to their apartment slightly outside of Oakland Chinatown’s 16-square-block radius.

"They were telling us that there are people in their building that don’t leave because they’re so scared. They feel like prisoners."

“They used to walk that 15-minute walk home freely. They were telling us that there are people in their building that don’t leave because they’re so scared. They feel like prisoners,” Owyoung says. Upon returning to their apartment building, the women recommended Compassion in Oakland to their neighbors.

Becky Kok, who moved to the United States in 2007 from Hong Kong, heard about the rise in violence from her group chats. Speaking to Oprah Daily through a translator, Kok says she used to rely on her son and daughter to drive her to destinations. Then she heard about Compassion in Oakland, first from a flyer and then from a neighbor. A volunteer accompanied Kok to three dentist visits in Chinatown. “This service saved me. It made me feel secure,” she says.

According to the co-founders, most elders know someone who has been harassed. “Everybody has a story,” Ramos says. But often, these crimes go unreported. “It’s embedded in the culture to move on and not speak about it. You don’t want to cause trouble. You don’t want to be the person who is too loud and draw attention to yourself. Culturally, that was something that maybe, for a time, helped people survive. But it doesn’t work anymore,” Owyoung says. “Younger generations are changing that.”

Compassion in Oakland is one of many groups around the country attempting to create a sense of security among the neighborhood’s AAPI elders. Volunteers are donating air horns to local businesses. The service Cali Kye Cab offers reimbursement for elders who have to travel long distances via Lyft. Asians with Attitude, led by two Bay Area fathers and their children, is another patrol group formed in the wake of the attacks. Among this sea, Compassion in Oakland volunteers are visible for their goldenrod shirts—contrasted, say, with volunteers for Oakland Chinatown Chamber of Commerce, who wear blue. “They walk in a big line. We see each other and wave as we pass,” Wood says.

The patrol groups operate on the principle of safety in numbers. “This is a community that looks out for each other and they will protect each other. Hopefully this will discourage people from committing violent crimes,” Wong says.

Unfortunately, the need for these groups’ existence continues to assert itself. In late April, Carl Chan, the president of Oakland's Chinatown Chamber of Commerce—who had spoken out against the year’s earlier attacks—was himself the victim of a hate crime.

While these incidents of race-based violence are now inciting national outrage, the residents of Oakland’s Chinatown have long been aware of this problem. “The elders are saying it’s nice that there’s been a response, but this isn’t new. They’ve been harassed on the bus for their whole entire lives,” Owyoung says.

Just as the problem is not new, it is not limited to Oakland. According to Compassion in Oakland’s founders, the largest spike in volunteers came following an attack on the other side of the country. On March 26, a gunman opened fire at three spas in Atlanta, Georgia, murdering six women of Asian descent, and eight people total. This act of race-motivated violence led to an influx in volunteers (the group more than doubled in size that week). “It showed people this is a bigger issue than they were wanting to admit and recognize,” Owyoung says.

In the months to come, Compassion in Oakland is expanding to San Francisco and the San Gabriel Valley in Southern California, and are looking to other cities with a sizable population of Asian elders. “Slowly, we’ll have the whole city of Oakland and beyond covered in these shirts,” Owyoung says.

So far, Compassion in Oakland’s strategy appears to be working: There has not been a reported incident of violence on one of their patrols. For the co-founders, the real measure of success is more ineffable than what statistics provide. Owyoung says, “It’s beautiful to see how relieved these elders are feeling. They say, 'You guys see us.'"

But, the group’s success is also bittersweet. “In a perfect world, we wouldn’t need this service," Ramos says. "These attacks wouldn’t be happening. People wouldn’t feel scared.”

Donate to Compassion in Oakland

You Might Also Like