Artist Rose Wylie Proves Success Gets Better With Age

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

A tour of Rose Wylie’s painting studio is like a visit to an archaeological dig. Wylie runs out of space frequently, so layering her paintings on top of one another is the only way to make room for new ones. “I heap, stack, and pile,” she says one December afternoon. “I have several going at once.”

I don’t know firsthand (I only hear about it during a phone call), because no one has entered Wylie’s farmhouse, in the English county of Kent, since lockdown began last March. No one, that is, except her tiger-stripe cat, Pete, and the masked art handlers moving the works she has made during quarantine, many of which have made their way to the David Zwirner gallery for Wylie’s first major New York exhibition, opening April 29.

The artist is 86. The paintings—oversize, exuberant pictograms richly grounded in storytelling—may look instinctive, with their flattened perspective and deliberate exaggerations, but they are, in fact, the result of much premeditation. “They’re not just a flash,” the artist says. “They’ve got a background to them.”

Wylie’s own background is unexpected for a painter described by Germaine Greer in 2010 as “Britain’s hottest new artist.” Seventy-six years old at the time, Wylie had worked in relative obscurity until that point. In the decade since, her success has snowballed.

She spent much of her life ensconced in domestic duties, a housewife to the late painter Roy Oxlade, raising their three children and painting when time permitted. She got an MA at the Royal College of Art in 1981 and began focusing on her art when her children moved out. The accolades came later. In 2010 Wylie was the sole non- American included in the National Museum of Women in the Arts’ “Women to Watch” exhibition; in 2013 she was featured prominently in a rehang at the Tate Britain; and in 2018 she was awarded an OBE for her services to art. In the last year alone she has been the subject of three international exhibitions.

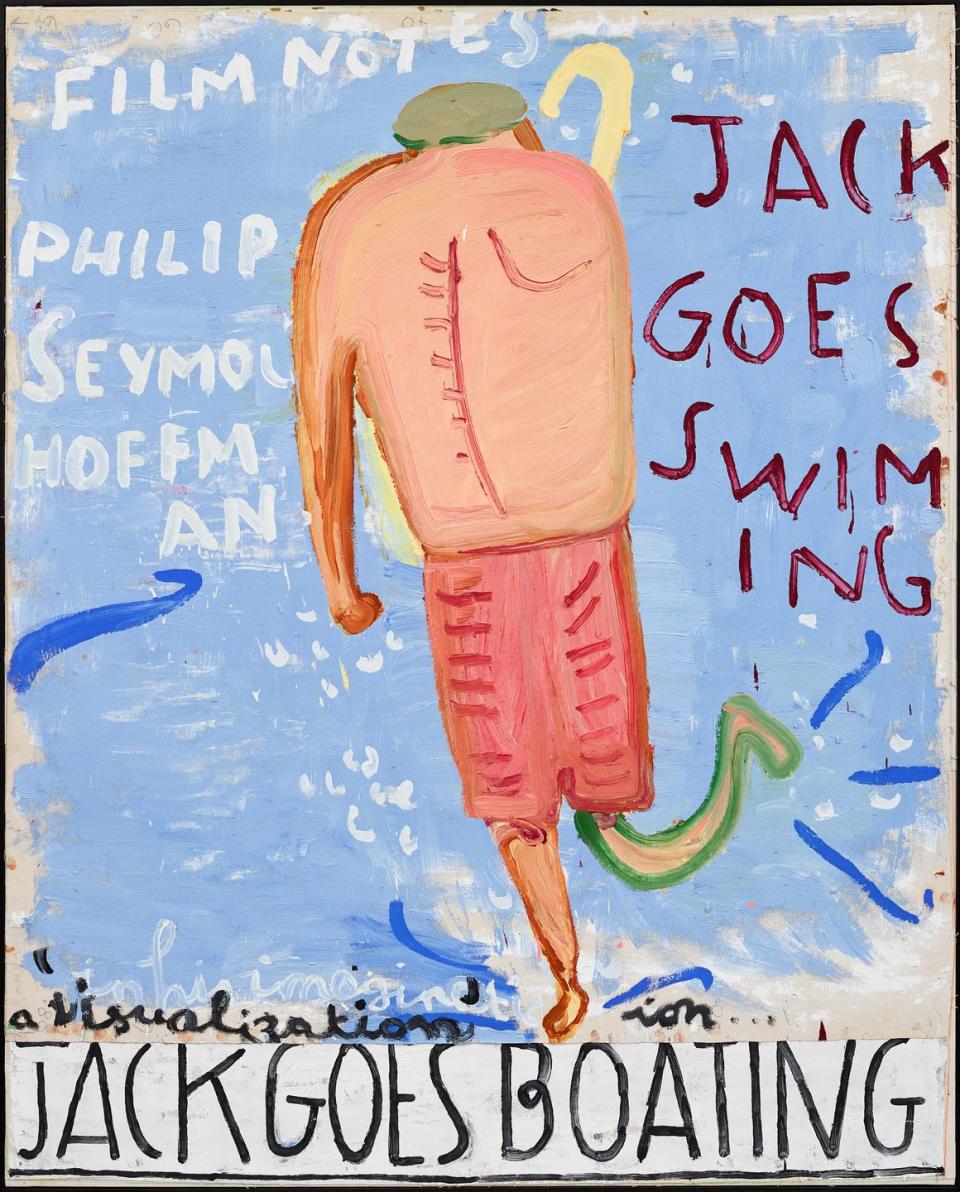

To extend the studio-as-dig metaphor, Wylie’s process involves brushing off objects previously overlooked in fine art. “It’s what’s around at the moment as you see it. If there’s something that’s visually exciting, I like to record it,” she says of her subjects, which range from Nicole Kidman in Cannes to a homemade omelet. Blocky text regularly anchors her pieces, serving as a blunt précis.

Her work is often compared to that of Philip Guston and Jean-Michel Basquiat. “It’s irritating, yes,” she says with a purr of impatience. “I understand Guston, but I’m also a fan of ancient mural painting.” Wylie bristles when adjectives such as childlike are used to describe her work. “It’s rather sloppy to say,” she notes shortly. “Nobody says that about Picasso.”

Critical terminology aside, Wylie’s long-awaited recognition seems not to elicit much agitation from the artist. “I’m used to people not paying the slightest attention to what I paint,” she says. “Then suddenly they do. I’m the same and the paintings are the same. But people now look at them.”

You Might Also Like