An anxious calm in Barcelona, as Catalonia prepares to vote on its future

BARCELONA — In the annals of bizarre political races, the 2017 parliamentary elections in Catalonia, Spain’s feisty northeastern province, may top even the 2016 U.S. presidential campaign in absurdity. At least Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump didn’t have to flee the country, and, despite frequent chants at rallies, neither was locked up in prison.

The regional elections to be held Thursday were called by the national government in Madrid, which eight weeks ago disbanded the regional government and fired its officials after provincial President Carles Puigdemont unilaterally declared independence for the free and sovereign republic of Catalonia. In tomorrow’s vote, the underlying issue is again independence from Spain, or, rather, the stance taken on that contentious matter by the seven competing parties, three of which support making the break.

Heading the separatist Together for Catalonia party, the deposed Puigdemont — who insists he is still president — is campaigning from Belgium, where he and four Cabinet members fled hours after declaring Catalan independence. Fifty thousand supporters traveled to Brussels to cheer him on last week, though any potential victory for Puigdemont is clouded by the likelihood that he faces arrest should he return to his putative capital of Barcelona.

Meanwhile, his ousted vice president, Oriol Junqueras, leader of the pro-independence party the Republican Left, is making his electoral bid from behind bars in Madrid; fearing that he might skip town like Puigdemont, judges remanded him to prison to await trial for rebellion, sedition and misuse of public funds, charges that could bring a sentence upward of 30 years. (Six other politicians from Puigdemont’s government were released from prison earlier this month, while Junqueras, the former secretary of the interior, and leaders of two separatist civil groups were denied bail.)

“I’m in prison because I don’t hide,” Junqueras said in a radio interview last weekend, taking a swipe at his former boss, whose party Junqueras declined to run with as a united bloc. Puigdemont countered that he was in self-imposed exile in Brussels for exactly the same reason, but Junqueras’s plight has gained him more street cred, to judge by the polls, which forecast the Republican Left winning around 22 percent of the vote to Together for Catalonia’s 17 percent.

According to most voter surveys, however, a “constitutionalist,” antisecession party leads: Ahead by a hair, the right-leaning Citizens Party is fronted by outspoken parliamentarian Inés Arrimadas, whose likeness is the most plastered (and, arguably, most defaced) across Barcelona. Clearer about what she doesn’t want — independence from Spain — than what she actually hopes to accomplish, Arrimadas, like many party officials, was not born in Catalonia, but in the southern region of Cádiz, prompting one separatist politician to suggest that she go back home; Catalan newspaper El Nacional branded her entire party as “anti-Catalan.”

A vote-weighting system that favors the countryside — which is more independence-oriented than regional capital Barcelona — could mean that even if Citizens and other “unionist” parties gain more votes, that won’t translate to more seats. Which means that the national government’s gamble that a re-rolling of the electoral dice would lead to a Catalan parliament where separatists don’t hold a majority may backfire — and Madrid may be back to square one in dealing with a restive region, where nearly half the residents want to bolt, and nearly half want to stay rooted in Spain.

“This election won’t resolve anything,” says Barcelona-based English teacher Roxanne Rowles. “Whether the independentistas win or lose, the issue will be stirred up again.”

That is exactly what separatists like Katherine McLaughlin, who owns a cheese store in Barcelona’s Gothic Quarter, are hoping. “As President Puigdemont put it, ‘Independence — yes or yes.’” She says the issue isn’t whether to secede, but when.

The secession drive is fueling expectations that voters will turn out in record numbers exceeding 80 percent. In apparent anticipation, the mood has cooled in Barcelona: Except for vandalism at antisecession party headquarters and dramatic displays of ripping up political posters, the provincial capital lately has felt like it’s in the eye of the storm. Since a November candlelight march to show support for imprisoned separatists, demonstrations have been few. But a quiet melancholy has descended on this usually festive city on the Mediterranean, a favorite destination of American tourists, more than a few of whom have put down roots.

The events of October, however, are far from forgotten. Ignoring warnings from Spanish Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy and the national courts that a vote on Catalan independence would be unconstitutional unless the whole country was voting, Puigdemont pushed a promised referendum on independence. Separatists hid ballot boxes and ballots to keep police from confiscating them. Held on a rainy Sunday, the illegal referendum was boycotted by most of the electorate, marred by voter fraud, and vividly remembered for dramatic scenes of police violence.

The results of the flawed vote were sketchy — Puigdemont’s government maintained that 43 percent of eligible Catalans had voted, returning a yes vote on independence by a margin of 90 percent — but the sight of police beating old ladies brought new supporters to the separatist cause, among them videographer Guillem Valle, 33, who is voting for the first time Thursday.

“I used to see parallels between Catalan nationalism and the Nazis that I didn’t like. But after the referendum, I started seeing behavior of the Spanish state that I didn’t like,” he says. “The shadow of the Civil War hangs over this.”

Yet, if the referendum caused some to switch to independentistas, others switched to the unionist cause, unsettled by Puigdemont’s wishful dreaming and lack of planning. During the confusing days of October, “for a while, nobody was sure if Catalonia could continue using the euro or would issue a currency of its own,” recalls Charles Fisher, a Californian who retired to Catalonia 13 years ago. That insecurity is toxic for business, he notes: Banks began moving their legal headquarters, followed by some 3,000 other businesses — several hundred of which moved out of the province.

Then tourism began nosediving: Hotel reservations plummeted 11 percent in October and are down 15 percent for the holiday season, resulting in an estimated loss of 450 million euros — some $530 million — in the fourth quarter.

“My sales are way, way down,” says Alexis Fasoli, who makes upscale leather goods in his atelier in the Born District, estimating his business has dropped by 30 percent since October. “I think we’ll be seeing a lot of small- and medium-sized stores close by March.”

And uncertainty has clouded locals’ spending habits, says pet store owner Chelo Díaz Jiménez, whose sales have fallen dramatically and who is hearing the same from business owners all over town. She’ll be voting in Thursday’s election, but is still uncertain whom she will vote for.

“I’m Catalan — I’ve lived here my whole life,” she says. “But as a small business owner, I’m not sure how independence would benefit me. Nobody’s explaining that.”

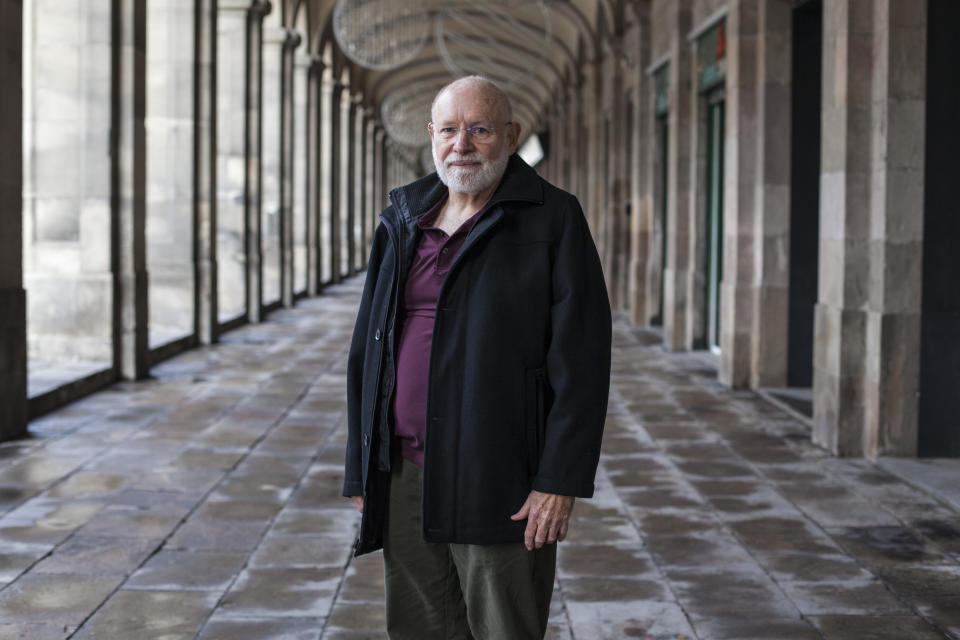

To Barcelona photographer Daniel Bartolomé Bermúdez, who comes from northern Spain and is not a separatist, this is all part of his country’s evolving democracy, which was only attained, after decades of dictatorship, in 1978.

“Catalonia and Spain don’t have a long democratic tradition,” he notes. And like videographer Valle, on the other side of the spectrum, he believes that at some point Spain will have to grant Catalonia a binding vote on independence. “The only way to find out what Catalans want is to ask them in a referendum, but the Spanish government doesn’t want to do that.”

Like many across Barcelona, he predicts that tomorrow’s elections, the fourth called in seven years, will result in a hung parliament, with no party in the majority, and no effective coalition able to form. “We’ll probably have another election in a few months,” he says.

Melissa Rossi, a writer based in Barcelona, is the author of the geopolitical series What Every American Should Know (Plume/Penguin).