Annie Proulx Is Done Fighting Climate Change. Now, She's Adapting To It.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

While climate change mainstays like polar bears, glaciers, and wildfires tend to receive an abundance of media attention, there are surprisingly vital, occasionally vast corners of our planet that often go almost entirely overlooked: the peatlands. Celebrated author Annie Proulx has set out to correct this.

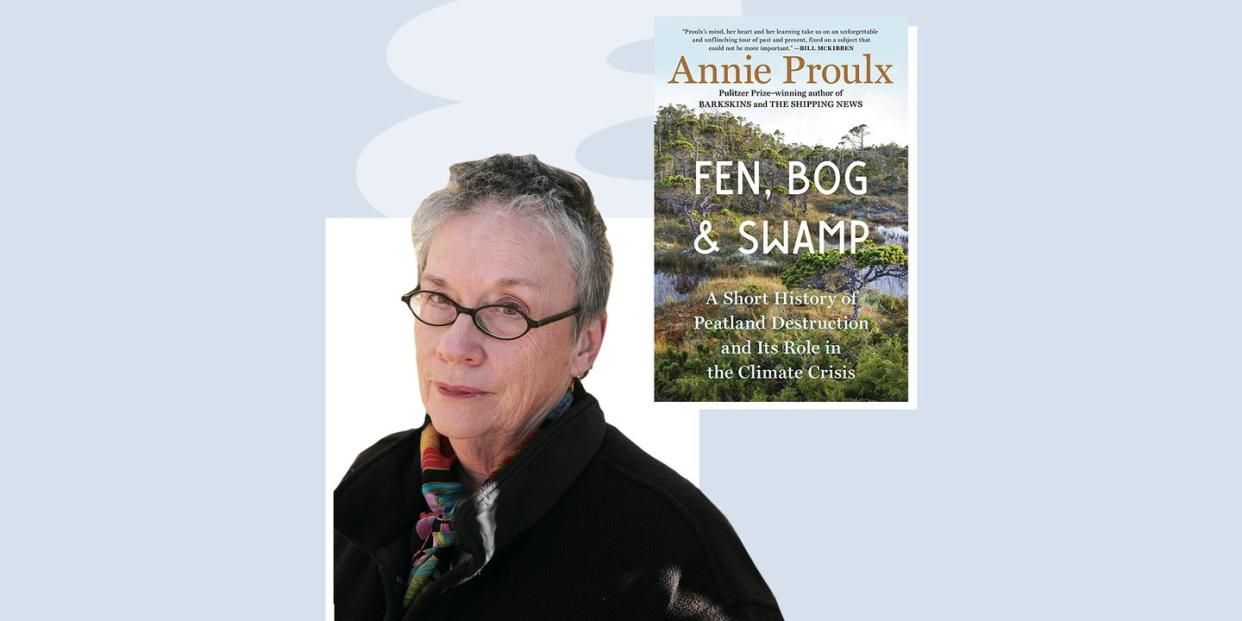

The writer of renowned rustic stories and novels such as Brokeback Mountain, Barkskins, and The Shipping News once remarked, “I’m at home in a rural situation and all of my writing has been about rural places.” Her latest release, Fen, Bog & Swamp: A Short History of Peatland Destruction and Its Role in Climate Change, certainly upholds her passion for the pastoral. Placing the spotlight on a diverse range of remote, rarely visited wetlands scattered around the globe, she makes the case that the protection of these places should be given greater consideration amid humanity’s uneven struggle against climate change. “Humans are exceedingly good at construction and destruction, but pitifully inadequate at restoring the natural world,” she writes in Fen, Bog & Swamp. “It’s just not our thing.”

In the book, Proulx reveals the extensive harm that civilization has inflicted upon wetlands, but also highlights those who are taking action to mitigate the damage. While pragmatic about the severity of the situation, as she explained to Esquire, Proulx also finds reasons for hope and even joy in the wide-ranging efforts to adapt in the face of an increasingly inhospitable climate. (This interview has been edited for length and clarity.)

Esquire: You’re primarily known as a novelist, and this is your first major work of nonfiction in a while. Why fens, bogs, and swamps? What about them caught your interest?

Annie Proulx: I have never liked the pigeonhole placement of writers. Once a romance writer, always a romance writer; once a short story writer, ever a short story writer. Publishers and readers tend to encourage such categorization. But one of the true pleasures of the occupation is that usually you can ignore the labels and write about what interests you.

In recent decades, I became increasingly aware that a great earth-changing event was underway with ramifications that were vague because it was all new to anyone alive today. Something massive was changing the entire world we knew and loved and depended on. It was even whispered that this might be the beginning of a mass extinction event that included more than birds or insects or plants—an extinction of humans that we ourselves had brought about. All the unknowns of a global climate shift surged over me. I knew very few of the details.

Among the evidence given for climate change was the measured certainty that CO2 was warming the earth, and that one of our protections was the earth’s absorbent sponge of wetlands, especially the peat-making wetlands. I started to read and learn something about those wetlands. My first effort was an essay, “Discursive Thoughts on Wetlands,” which I showed to my agent. She suggested enlarging the essay into a book. By then I understood that the peat-making wetlands were successional and that each stage had a distinct character. I settled on the related fens, bogs, and swamps as an interesting subject. Because I am not a scientist, my examination was historical and anecdotal. The little book that came from my digging around is only a bare sketch of humanity’s relations with the wetlands of earth.

ESQ: Early in the book, you cite a time before “poisonously intoxicant politics.” What change have you seen in this regard over the course of your life?

AP: In my childhood and young adult days, the two parties seemed not all that unlike each other. My parents were mild Republicans and politics was never a common subject in our household. Politicians of every type gave off a certain disagreeable odor, though WWII seemed to have made a kind of solidarity—Democrats and Republicans could sit at the same dinner table without snide remarks or attacks on each other. Each declared a belief in “democracy” and each admired Norman Rockwell’s Saturday Evening Post covers.

But when in the time of Al Gore many people began to notice and talk about disappeared forests, lake and river pollution, ripping away the mountain tops to get at the coal inside, building polluting factories on the banks of some of the country’s most scenic rivers, the outrageous idea of environmental protection emerged. The ideas had been around for some years, mostly praised by “nature lover” nuts. Almost immediately, caring for and restoring damaged parts of the natural world was seen by business-minded Republicans as a dangerous folly that would destroy jobs and hurt the chances of individuals and companies to make money. There was the strange belief that nature could always repair itself infinitely, no matter what was done to it. Rather swiftly, the Republican Right mixed the idea of the perceived environmental threat to business into its politics. This brew was served as a carelessly poured bottle of red wine at a white-tablecloth dinner. Everything got stained. And “democracy” began to be shown up as a kind of weak lemonade.

ESQ: Why have “bog corpses,” which you explore in the book, attracted such fascination?

AP: Bog bodies, mummies, the corpse in the library—endless detective stories and murder mysteries all show that we have a kind of morbid fascination in unknown corpses. With ancient bodies, we want to know not only what brought these people to their ends, but who they were and how they lived their lives. We don’t know, we can’t know, but we want to know what happened. Perhaps the “why” is our in-built hunger for stories, or perhaps it is related to the slowdown of traffic passing by a vehicle accident—a kind of learning about danger that will make us wary of suffering the same event ourselves.

ESQ: You mention the conclusions drawn by researchers that were later found to be inaccurate (in regard to bog drownings as punishment for homosexuality, for example). Are there any commonly accepted climate change conclusions that you think are erroneous?

AP: Perhaps you are suggesting I say something about climate change denial and deniers? Indeed, there are people—many people—who refuse to (or can’t) believe that a true massive change in climate is happening, who reject the evidence of increasing heat, melting glaciers, rising sea level, torrential rains, and powerful long-lasting drought, all pointing at species extinctions in the future. I think it's human to deny that these events are meaningful and even deadly serious. It's certainly a comfort to think that such disturbances are temporary and that in a few days or months or next year, everything will be back to normal—but time will take the last grin, because slowly our idea of “normal” will change to fit the reality, however fierce it may be.

Denial of climate change may actually be proof that a great change is occurring. We feel uneasy; we sense that something is wrong. But we tell ourselves that our earth is immutable, that it cannot be changing in these dramatic and dangerous ways. There is also some belief that technology can somehow turn the warming trend around, shelter us from the sun. The dangers of hurling particles into the sky or minerals or chemicals into the ocean are obvious: once you do such a thing, you are stuck with the results. Many see the results are likely to be dire.

ESQ: When discussing the draining of wetlands, you make several tongue-in-cheek references to the resulting “most productive soil in the world.” I think you’d agree that our society tends to have a rather toxic concept of “productive.” Where do you think this mania for productivity comes from?

AP: This summer I went to a sale of history books, photographs, and pamphlets. I found an 1825 self-published book: Annals of Portsmouth, by Nathaniel Adams. Adams was the first president of the Portsmouth Athenaeum and the founder of the New Hampshire Historical Society. Adams began his book with these opening sentences: “The discovery of America excited in the minds of the Europeans an insatiable desire of obtaining riches. It opened to them new sources of wealth, and induced many persons to leave their native shore and cross the wide extended ocean in pursuit of gain.”

There you have it: the very first words in the book written almost 200 years ago tell of our insatiable desire for riches and the pursuit of gain that would come from the fantastic natural resources of this country. Nothing about freedom or democracy—just the bare obvious truth. “Productivity” seems to me the current word for getting what you can from what is available. We have exhausted many of the country’s natural resources and now still must get something out of what is left of soil, timber, water, minerals, labor. Greater “productivity” seems a way to get the last drips of value, just as one might squeeze the remaining drops of juice from a lemon wedge onto our baked halibut. It is an urge built into our national character—take what you can and leave the rest unless greater productivity will bring in a bit more profit.

ESQ: What do you see as the standout climate change catastrophes of the past century? What about the standout achievements in regard to fighting it?

AP: This is something of a trick question, as it is not new and terrible catastrophes that can be laid at the door of climate change; it is a progressive and uneven increase in the severity, length, and frequency of age-old disasters such as flooding, heat waves, droughts, forest fires, water loss, intensifying acidification of the oceans, glacier melt, and much more. At what point does the rising heat of summer start to kill off humans and wildlife in notable numbers? Is a new period of migration opening as those humans and animals, unable to adapt to the changes, seek better places to survive? How long before there are no safe places? We are told that climate change is beginning to speed up past its predicted rate—everything is happening sooner, more intensely. I personally think the key words might be “adapting to it,” not “fighting it.”

To choose just one catastrophic event aided and abetted by climate change, I would follow the reports on increasing numbers and ferocity of wildfires. Here’s a good site for scientific information on the great conflagrations. Climate change is warming the earth. We are seeing more intense and longer heat waves. A long dry period dries out the land, withers plants and trees, and increases the fuel load. Regions traditionally cold and wet featuring snowpack, glaciers, and permafrost are melting much faster than expected. The seasons themselves are shifting—it is called “season creep." As evergreen forests dry out and weaken, hordes of pine beetles move in and finish them off. This was something I saw first-hand in the lodgepole forests of the Rockies when I lived in Wyoming in the 1990s and early aughts. The very idea of fire burning in the moist and steamy Amazon forests could not be imagined when I was a child. Now it is a reality. Fires burn in the Amazon, in the Pantanal, in Siberia, in a hundred thousand places that once were damp and rainy. One of the most worrisome problems is the drying-up of water reservoirs, rivers, and streams. We may rightly worry about the world’s water supply.

ESQ: At some point, you refer to yourself as a cynic, and there is sometimes a pessimistic tone to the book. Is there any reason for optimism?

AP: I am not a cynic. I referred to myself as one only in the matter of Obrador’s orders to destroy mangrove forests for the sake of the Pemex oil refinery after signing the Paris Accord. He is the cynic who wishes to have his cake while eating it.

I disagree that Fen, Bog & Swamp is a pessimistic book. Throughout there are many examples of restoration projects both local and large. I stress the joyful possibilities of getting involved in a wetland restoration. We have only to talk with someone who worked on the extraordinary restoration of the Elwha River in Washington to have our hearts lift. Every time I hear of hopeful new plans to save wetlands, I experience a surge of delight. Notable is an undertaking to restore the salt marshes in San Francisco Bay and in New York, the Jamaica Bay marshlands.

From all the wetland revivals, a new questioning attitude toward natural catastrophes seems to be emerging that asks: in the long run, can flooding be looked at as nature’s restoration of habitats and environments? To date, we have only looked at what damage is done to human activities and uses, but flooding does more than destroy houses and roads. We need to learn how the greater wild system works and cooperate with it as much as we can. How much did the 2020 pandemic “anthropause,” when the world and oceans were quieter with less human bustle, affect the natural world?

I think the human yearning to repair and protect is greater than its urge to smash and run. The natural world gives us much more than goods and profits; it has always been a source of emotional and spiritual uplift. It does something beneficial to the ways we think and live. Those narrow-purposed humans who can only take and take as their two-legged right are not going to make it. We need to get involved with saving natural places if we want to save ourselves.

ESQ: Most people who are aware of and concerned about climate change feel powerless in the face of it. Do you have any guidance for people looking to contribute to the fight?

AP: Probably the most important thing every American could do is to get rid of or reduce the size of their grass lawns. These boring and sterile plots need constant care and nurture very few other life forms. They involve home machinery for mowing, rolling, and such. They are responsible for the loss of bumblebees, butterflies, frogs, birds, and so forth. I am well aware that many Americans would rather choke to death than lose their lawns, but for the die-hard lawn lover it is possible to cut down the acreage of the greensward and put in a few beds of pollinator plants and shrubs—introduce some life to the wasteland. Reducing the neighbor noise of mowers and blowers is another benefit. I am trying to reshape the large lawn of my current house: adding a wildflower meadow in the sunny part, encouraging moss and native fens in the shady edges. I am learning a lot.

Obviously, I do not agree that most people feel powerless to be part of adapting (you say “fighting”) to climate change. As far as wetlands go, anyone can pretty easily find a way if they take the trouble to look. Almost every state has a list of its wetlands and their locations.

ESQ: How can a writer like me make a difference in the face of climate change?

AP: You as a writer can make a huge difference. For instance, you could adopt a nearby wetland and learn everything about it and write about what you discover—varieties and behavior of dragonflies, snapping turtles, rare swamp plants rapidly disappearing, water snakes, mosses and blueberry bushes, people who visit your wetland and why they do that. You can be part of a conservation group that wants to rejuvenate an oily wasteland of rusted drums, car parts, bags of garbage. You can be someone who plants sedges and reeds. The more you learn, the more you see a way to be part of it. I am sure you can think of many more ways than I can of how you can be part of repairing what has been damaged. And as months turn into years, you will be happier for your involvement. No lie.

You Might Also Like