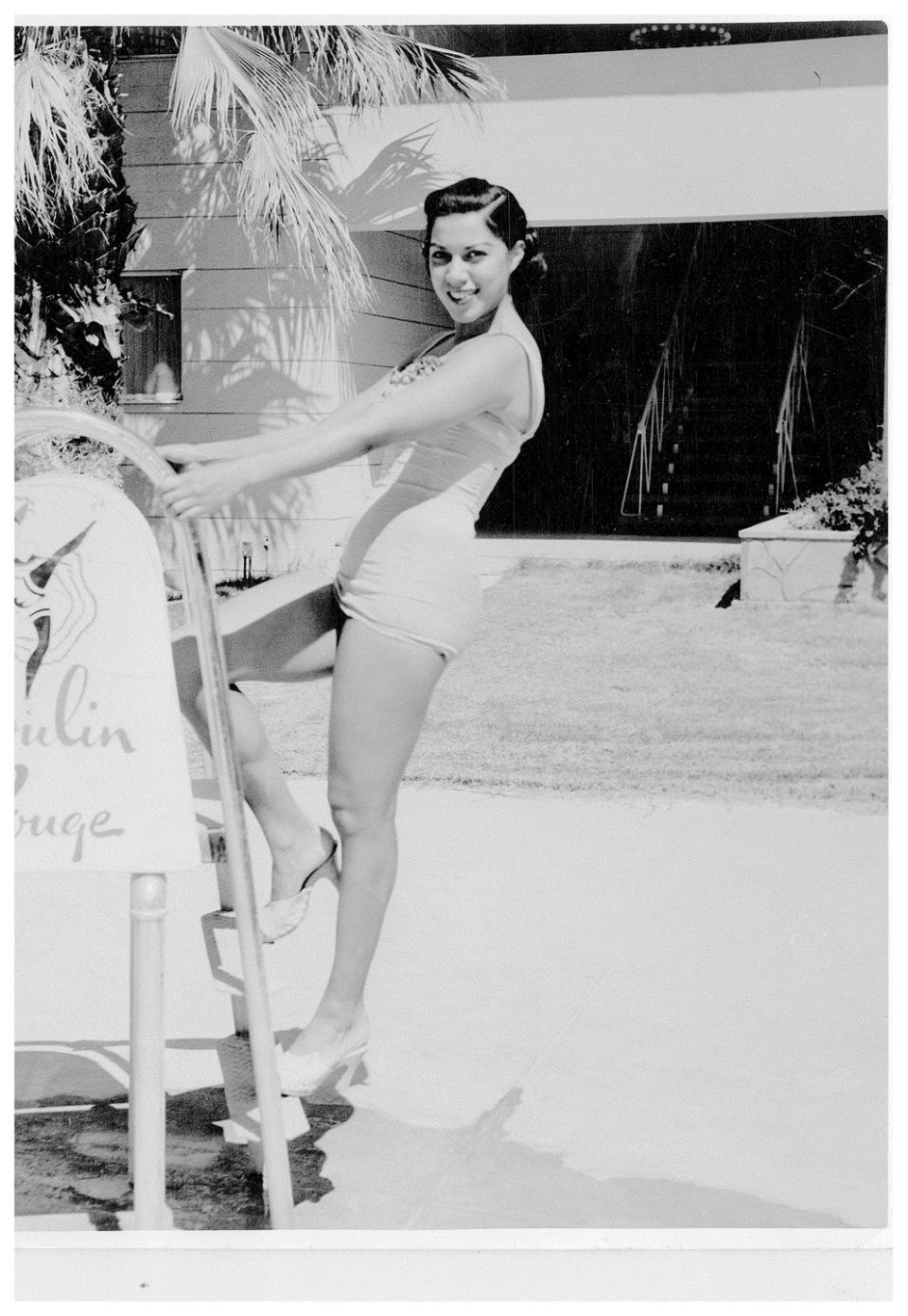

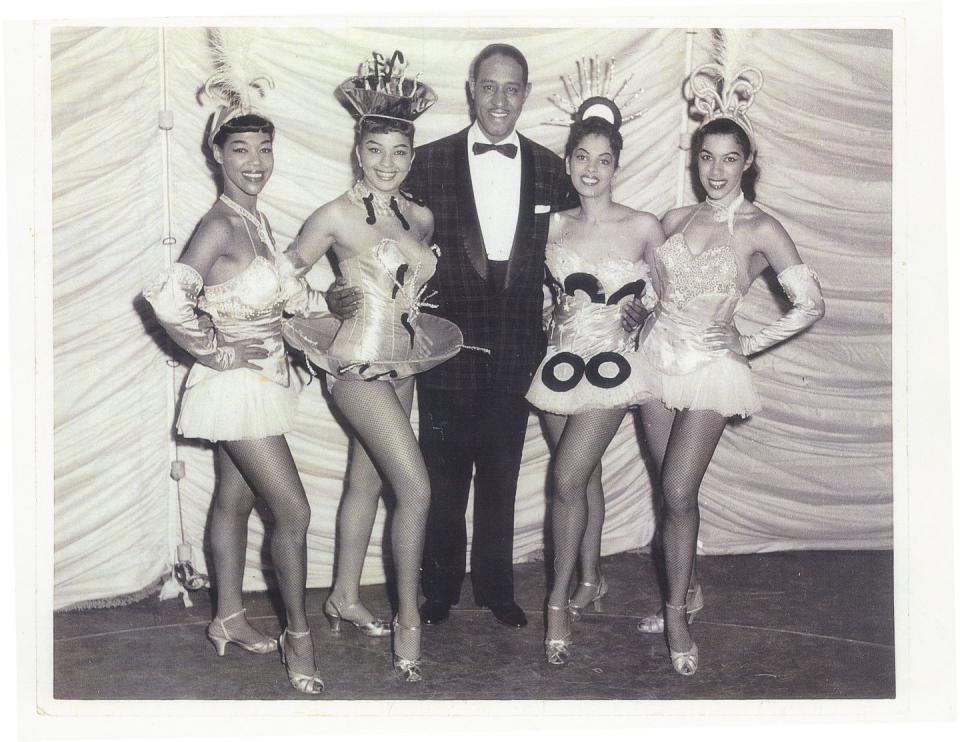

Anna Bailey Made History as the First Black Vegas Showgirl

“Hearst Magazines and Verizon Media may earn commission or revenue on some items through the links below.”

Interview by Rachel Williams/

Photograph by Da’Shaunae Marisa

In the early 1960s Anna Bailey became the first Black woman to work as a dancer on the Las Vegas Strip, at the Flamingo hotel and casino. She and her husband went on to open successful clubs.

Rachel Williams: You were performing at the Apollo at a very young age. Did you have any influences, or people teaching around you, who made an impact on you?

Anna Bailey: I hate to name-drop, but Pearl Bailey was a great influence. Even though my last name is Bailey, we’re not related, but she would call my husband “Cuz” and me “Cuz.” And she always told me to go to Las Vegas, because that’s where you need to go if you’re going to stay in the business. Her brother, Bill Bailey, always would tell me if I was dancing before the music, if I was dancing too fast, or if I wasn’t dancing on time.

RW: How did you rise so quickly in your business?

AB: I think I was just at the right place at the right time, and I never really had any kind of problems. You know, if I was booked, I would just go and I was always on time, and worked my hardest, so people were always glad to hire me. And I stayed busy until 1955. That’s why I was booked in Las Vegas at the Moulin Rouge, and then I was really blessed to integrate some of the shows at the Dunes and the Flamingo Hotel. So, I never really had any problems. I went from one job to the next job. Sometimes I wouldn’t even answer my phone because I might want to stay home a little bit.

RW: What inspired you, exactly, to move to Las Vegas?

AB: Well, we were in Buffalo, New York, and we were with the Clarence Robinson Show, and Pearl, like I said, had always told us about going there, and then when he come in and said we were booked in Las Vegas, we were just thrilled. And they flew us out, and we got off the plane, the photographers were there, and then we went to the strip, and we thought that’s where the Moulin Rouge was, and then when it turned left and went under the bypass and the railroad tracks, we said, “Uh-oh”—we were just really kind of nervous. But then, when we saw the Moulin Rouge, it was just beautiful. The best lighting. The best room showers in the dressing room. It was lovely. And I just can’t understand today why it closed to standing room only.

But I think that the Mafia, that was definitely there then, and I think they had something to do with us closing kind of early. We were the only ones that did a 2:30 show, because they just did an 8 and 12 and we did a 2:30, and the strip was empty, and they just couldn’t have that. So, in six months, we were closed.

Kimberly [Anna’s daughter]: The Moulin Rouge was white-owned by these two guys, and Clarence Robinson told them that he wanted them to be a part of the show. This was the first integrated hotel in the country, the Moulin Rouge. And so, he told my mother and my father, in New York, that he wanted them to be a part of the show. They were just hired to come and be a part of the show.

RW: What was life like for African Americans in Las Vegas at the time?

AB: Oh, girl. That’s a good question. Very hostile. But they could tell by the way we walked, the way we carried ourselves, the way we were dressed when we would go downtown, that we didn’t have any problems. We had little problems with the dress shops and things like that—naturally shops and theaters were segregated there. Like Woolworth, places like that, eating at the counter. The environment was very hostile, but there were very nice people too. There’s good and bad, no matter where you go.

RW: Did you face any specific hardships being in the entertainment business in Las Vegas, as a Black couple at the time?

AB: Yes. We did go to the Sands hotel one time, and we were really looking pretty good. We were young and really dressed, and the security guard took it on himself to stop us at the door. And this is really the truth: Frank Sinatra did come and get us, and took us over to Sammy Davis’s table, and he was just beating on the table because he was just so embarrassed for us. But we were young, and we wasn’t embarrassed at all. We just laughed it off—we were just so happy to be with Sammy.

Kimberly: My father talked in his book, Looking Up! Finding My Voice in Las Vegas, about how he and Nat King Cole once tried to go into a club on the strip, at one of the hotels, and they denied them entry. And my father said, “Well, this is Nat King Cole,” and the doorman said, “I don't care if he’s Black Jesus. He’s not coming in here.”

RW: After you left the Moulin Rouge, you went to start auditioning to be a dancer?

AB: Oh, no. I’d been dancing for a while. I’d been to Europe and everything. So, I went into the Dunes, and then, after that, I integrated the show with Pearl Bailey at the Flamingo hotel, and worked about five years there.

RW: So, being a showgirl is all about glamor and beauty, but Black women, especially at that time, were sometimes seen as less attractive, because they didn’t fit society’s typical beauty standards. Did that affect you at all?

AB: No, because we would wake up and make up. Put on those eyelashes and just go for it, and the designer clothes from that time. I don’t bother with it too much now, but during that time, we were really high-fashion ourselves.

RW: Were your experiences working these clubs different from those of the other women?

AB: Yes, let me tell you something that I was really so happy about: Some of the white ladies that were in the show, they had to mix afterward. They’d have to go to the casino, and act like they were playing the games at the gaming tables. But me being of color, I didn’t have to do that, because they were segregated. So that was a blessing for me. Every time after the show, I’d say, “Bye-bye, I’m going,” and they would be so envious of me leaving. That’s one thing I really remember that I didn’t have to deal with, and that’s at the Flamingo and the Dunes and the Rouge.

RW: With all your experience, what are you most grateful for?

AB: Oh, I’m just grateful to be alive. All my friends—I look at my little scrapbook and I look at my telephone numbers—they all kind of left me. All the dancers. We were like family. If you’re in a show for three months or a year, you’re family, so I’m grateful for that experience that I had, and the lifestyle that I have. We’re not rich or anything, but I’m happy to be in California now, and I can go back between La Jolla and Las Vegas. And then I can still talk to you and put one foot in front of the other—I’m grateful for that. God is good.

RW: How has the art form of performance in dance shaped your reality?

AB: Well, it gave us a sense of confidence that we can walk into a place anywhere, with our chin up, shoulders back, stomach in, and walk with a little attitude. Show business was good training for me, to learn how to just meet and greet people of all levels. It was like a school, and the people that you meet all over the world, and that’s when you’re on tour, you’re everywhere. You’re down South—that’s another story—and you’re going coast to coast, and you’re going to Europe, you’re going to South Africa.

Kimberly: She remembers knocking on doors in the South to have a place to stay when they were on the road to see if they could sleep there, because the hotels wouldn’t allow African Americans to sleep in the hotels.

AB: And I think back on those days, how, the nerve we have to knock on someone’s door and ask if we can stay? But they had billboards that told everybody that we were coming to town, so, they were aware that we were there, and then we paid them. But to bring strange people in your house like that, and we had the nerve to go and sleep in someone’s home.

That was in the Shuffle Along show. I don’t know if you heard of Shuffle Along. You’re too young for that. That’s way back, you know.

RW: I’m only a measly 22.

AB: Oh, you’re a baby. Oh, golly.

Kimberly: You could be my daughter.

AB: You could be my granddaughter.

RW: What I’m hearing is that although you were able to live out your passion, dance, travel, and do it all over again if you could, there was still a level of adversity that you faced. I believe adversity is directly related to change. What are some of the adversities that made you who you are?

AB: I went to a theater one time, and the Blacks had to go upstairs, and for some reason, I don’t know what got into me, maybe I was young, I went downstairs and sat there. I couldn’t enjoy the movie because I was waiting for somebody to touch me on my shoulder. That’s the stuff you have to go through, and that’s the part I didn’t like too much. That’s why I just enjoyed, so much, growing up in Brooklyn, because I didn’t feel that, really, until I went to the South or when I went west. I didn’t feel it in New York.

And when there was an audition, you’d just go. The only thing I didn’t make—I was passed by Radio City Music Hall, but I was a little ahead of my time.

Kimberly: You wanted to be a Rockette.

AB: I wanted to be a Rockette. I did. I wanted to be one so bad. But like I said, I worked on Broadway a lot. I worked on Broadway, more than I did anywhere else.

Kimberly: She can still break out in a time step.

RW: And I believe it, too. What message would you send to young Black performers today?

AB: I would say to do the best you can when you go out on that stage. Be ready. Have your routine together. And work your hardest. You get a good job, keep it. Just work hard and save your money.

Kimberly: Emphasis on save your money. My mother hasn’t told you, but many of the businesses, really all the businesses my dad opened, my dad was so busy doing so many other things, but she’s a businesswoman. She’s the one who did all the accounting. She counted the money every day. I grew up behind a bar, and I’m just saying, she was an A1 entrepreneur, every check. I just remember her counting all of that money, but everyone, even though it was situated in the historic Black Las Vegas of the west side in Las Vegas, everyone treated her, even to this day, like royalty, because of the way she carried herself. And she would go into that bar, and they might be alcoholics, or people acting crazy, but they would straighten up when she would come in.

RW: Now that you have gotten the chance to do everything you could imagine you wanted to do, what do you enjoy doing now?

AB: Well, now, I still like to travel. I’m glad the pandemic is over, because I’d like to go to Argentina. I’d like to go to Havana. I want to go to Cuba.

Kimberly: And she wants to meet Oprah Winfrey. That’s always been in her wish list.

AB: It was, but I don’t think I’ll be able to talk to her. I’d be so nervous. But she’s made me so relaxed. I’m proud of what she did with her life.

About the Journalist and Photographer

Turn Inspiration to Action

Consider donating to the National Association of Black Journalists. You can direct your dollars to scholarships and fellowships that support the educational and professional development of aspiring young journalists.

Support The National Caucus & Center on Black Aging. Dedicated to improving the quality of life of older African Americans, NCCBA's educational programs arm them with the tools they need to advocate for themselves.

This story was created as part of Lift Every Voice, in partnership with Lexus. Lift Every Voice records the wisdom and life experiences of the oldest generation of Black Americans by connecting them with a new generation of Black journalists. The oral history series is running across Hearst magazine, newspaper, and television websites around Juneteenth 2021. Go to oprahdaily.com/lifteveryvoice for the complete portfolio.

You Might Also Like