American Workers Have Seen the Matrix

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Remember all those breathless death knells for the office from back in March '20? “We’ll never go back to the office again,” they said. “Working from home is the future,” they said.

Boy did that not happen. Nearly two years later, expectations and reality have yet to catch up with one another. In workplaces around the nation, employers and employees are renegotiating where and when work gets done; some employers are dragging their workers kicking and screaming back to the office, while others have rushed headfirst into the work-from-home revolution, only to build shabby wings on the way down. Meanwhile, we’re living through a paradigm-shifting moment in American labor history: a childcare crisis, rampant inequality, and a toxic culture of hyper-individualist workaholism, among other factors, have left the labor force both disenchanted with work and sickly in thrall to it. The way forward remains a work in progress, but a dam has broken open.

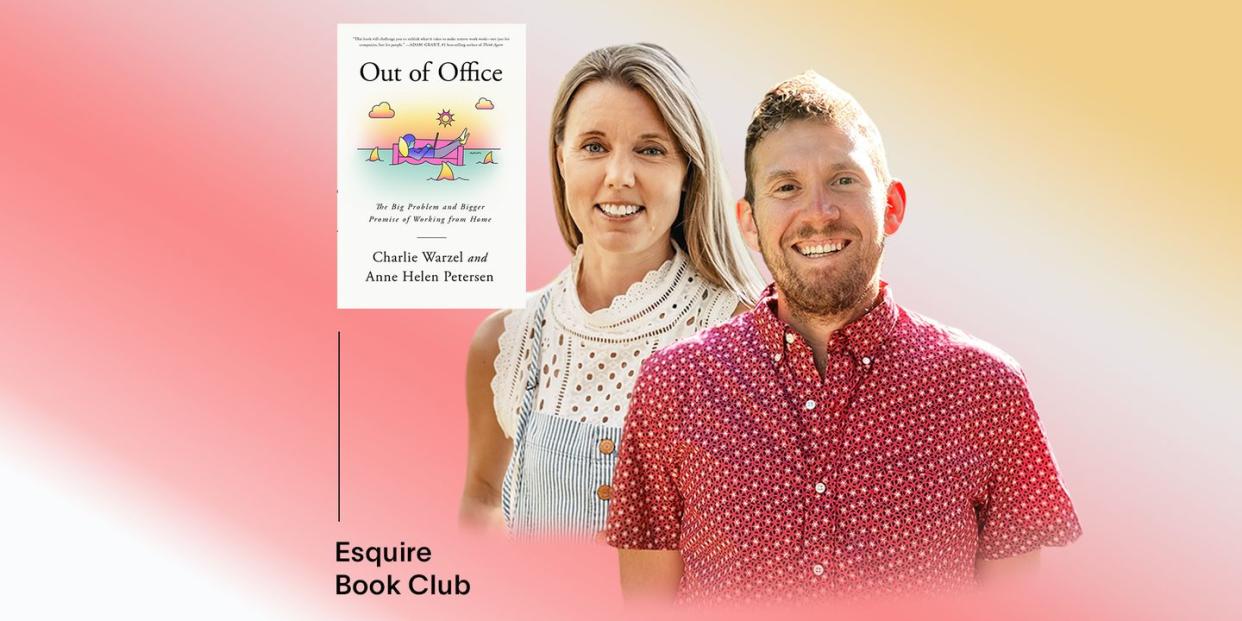

In their new book, Out of Office: The Big Problems and Bigger Promise of Working From Home, journalists Anne Helen Petersen and Charlie Warzel grapple with this cultural awakening. Petersen and Warzel dig deep into the future of work—and the importance of redefining not just where, but how and why we do it. They arrive at an elegant solution, obvious in its simplicity and maddening in its seeming impossibility: “less work, over fewer hours, which makes people happier, more creative, more invested in the work they do and the people they do it for.’’

But is that future really impossible? How do we get from the present’s broken promise to a more equitable future? These are the million-dollar questions in Out of Office. “There’s no easy fix,” Petersen and Warzel remind us, “just the hard, continuous work of stripping out what’s broken and designing the future based on the present.” Petersen and Warzel spoke with Esquire by Zoom to discuss the false promises of corporate life, the urgency of change, and what work could look like if we dare to dream bigger. This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Esquire: Reading the book, I got to thinking about the term “work-life balance”—a term that seems so antithetical to your argument. It frames work and life as forces in opposition, or work as a thing wholly separate from life. Where do you think our language around work, or our ideas around work, are the most ossified? What from our parlance of work would you like to see struck from the lexicon?

Anne Helen Peterson: The first one, for me, is boundaries. Like "flexibility," "boundaries" is a word that’s used so much as to become meaningless. When you talk about having any boundaries, or a company claims to be good at maintaining boundaries, it often means there are no boundaries. What they’re actually promoting is a total subsummation of life by work.

Charlie Warzel: For me, it’s the idea of companies as families. Families are dysfunctional, but you tolerate that dysfunction because there's a blood relation. The family language is a company asking you to make extreme sacrifices on their behalf with no reciprocation. The company at any point can say, "We're really sorry, but we just didn't hit our targets. We have to downsize. It's not personal." Well, family is personal. Really, it’s a one-sided family dynamic where workers historically get burned.

Another scrap of language that needs to go is this idea of, "Are we returning to work? Or are we completely working remotely?” That’s a false binary. The actual future will be everyone finding their equilibrium, as both companies and individuals figure out what works for them. This idea that we’re all going to snap our fingers and no one's ever going to enter an office again, or that we're all going to snap our fingers and every single person will be back in the office—it’s just not speaking to the reality of the situation.

ESQ: You surveyed over 700 workers for this book. What jumped out at you from that data? What were the through-lines?

AHP: One of the main questions that we asked in that survey was, "How long would it take you to actually do your job every week if you were working efficiently on the tasks you need to finish every single week?” The answer was comparatively little. We’re talking 20 to 30 hours. It was very clear that given the right conditions to focus, there wasn't actually that much work to be done. All the rest of it is this elaborate performance of office language. I thought that was really illuminating.

ESQ: I’m reminded of what you write in the book about “metawork”— the noise that exists during work, like Slack pings, pointless emails, and overlong meetings. Perhaps if we cut down on metawork, we could be in and out in 20 hours.

AHP: There’s something to be said for having conversations about work with coworkers. We're not saying we should get rid of all meetings, but the core amount of work oftentimes gets slowed down by these distractions. Here’s a really interesting example: an advertising agency found that their workers were more distracted than ever when working from home, because the creatives’ time for deep concentration was inundated with alerts from the salespeople. Their solution was to block off three to four hours for the creatives to dig into deep work. It’s not like the salespeople couldn’t work during that time, but they couldn’t get in contact with the creatives. It segmented off an uninterrupted parcel of time where people could dig into that deeper creative flow.

CW: Sometimes, we get stuck on this idea that it’s just distractions. If someone could sit down and bang their head against the wall uninterrupted, something could get done. But what the remote experience shows is that many of the ways we used to work are actually antithetical to the way the brain works. Why are some people having such productive moments when their kids go to sleep? Sure, it’s that there are no email alerts, but it’s also that in the space between picking the kids up from school and putting them to bed, you've got this six-hour break from work. But that whole time, your brain is working. It’s still processing and thinking; then when you sit down, you’re ready to go. If we think of the work day as a technology in its own right, it's a distracting technology, because it doesn't give your brain any time to rest.

ESQ: This reminds me of something you write in the book: “Working from home is a discrete, defined skill.” We think of professional skills as related to the work we do, whether it’s crunching numbers or making slide-decks, not related to the methodology of our work. How can we develop and improve our working from home skill?

AHP: Even just the acknowledgement that this is the future is a really huge thing. Some workers had that moment over the course of these past two years spent working from home. Whether it was May 2020, when people were like, "This isn't going to go away anytime soon,” or even last winter, when their backs started hurting and they thought, "I’ve got to get a more permanent solution." Right now, people are reaching a moment where they wonder, "How can I make better habits so that I don't feel like I'm working all the time?” It takes time to make those habits feel like a compulsory part of your day. That includes getting outside, or taking an actual lunch break away from your computer—there are all sorts of things you can do to make remote work feel more survivable, more dynamic, or maybe even more like something better than the office.

The other thing is that we're still hampered by the pandemic. People don't necessarily feel comfortable going to a co-working space, or to the library, or a coffee shop. Moving forward, these places will make working from home feel more dynamic. Part of it is that you need to figure out your own on- and off-ramps from work—those buffer spaces that we used to have in the form of a commute. What is that going to look like for you? The second thing is understanding that there's going to be a lot more possibilities, moving forward. They're not here yet, but they're going to be here.

ESQ: You touched in this in your newsletter when you wrote about working remotely from a kitchen table with friends. That seems like such a radical change—the notion that we can work remotely in a social way, rather than sitting alone in our home office spaces.

AHP: Working in that way can alleviate the loneliness that oftentimes stems from work. How great it is to work with people in different industries? You have skills to give one another, and you have a safe space to let off steam. It's cross-pollination.

CW: There’s something radical about working with your friends at the kitchen table. Offices tend to be bullies in the sense that they can intimidate you. The prestige of your employer, having your boss lurking over your shoulder—that can make the highs seem really high, but the lows are really low and scary. There's something about the kitchen table with your friends that removes some of the anxiety from work—the domineering corporate nature of it. When you're in the office or when you're totally alone, a setback can feel precarious or spirit-crushing. But when you’re with a supportive group of people who form the other part of your life, you remember, "This only matters so much, because I have these people too." I think that's really crucial, because it’s one way workers claw back small pieces of power.

ESQ: You write about how work has become the organizing principle of American life, and how, “for so many so-called knowledge workers, [work has] become an identity above all else, slowly eroding the other parts that make a rich, well-rounded human existence.” If we achieve a future where work is decentralized, what will fill the void?

AHP: I think a lot of people who aren't full-time workers have struggled with this question for a long time. If someone is disabled and they can't be in the workforce, how do you answer that question? How do you ask other people about themselves? I've learned a lot from having conversations with people in those positions. Basic switches in conversation, like “what do you do for fun” rather than “what do you do,” are fundamental to rethinking this. So, how do we start to change? Some of it is that rhetorical shift, making that change of how we conceive of other people and their value. But the other thing, going back to Charlie's previous answer, is building up things in our life that aren't work. We have these infrastructures that aren't work, but it’s a difficult thing to detangle; it’s a chicken and egg problem. Some people say, " I can't volunteer regularly because I work all the time." Because you can't volunteer regularly, you don't have any infrastructure of care and community work. Or, someone will say, "I'm scared of working from home all the time, because then I won't have my work friends, and I don't have any other friends outside of work." Part of the reason you don't have any friends outside of work is because you work all the time. How do we end this reliance on work as the structure of our daily lives?

As for us, we’ve never been able to make a weekly volunteer commitment, because we used to travel all the time for work. Rightly, volunteer organizations like the food bank want someone who can be there every week. Just for an hour, but you need to make the commitment. It’s going to be hard to say, “This is on our schedule every Thursday. This is what we’re doing." But if my job told me I needed to be in a meeting every Thursday at a certain time, I wouldn’t question it. You just have to say, "This is going to be the part of my week where I do this thing."

CW: When you spend more time away from the job, you generally meet people who work in completely different jobs. You start seeing those people as equals, individuals, neighbors. It changes the way you see the world. I think it really helps decenter your own idea of yourself as some high-minded knowledge worker. You start to see everyone as a person of value. That changes the way we can advocate for each other. When we see everyone as another worker, it promotes worker solidarity. Right now, everything feels so precarious in our jobs. We're just fighting to get through the days; in this hyper-individualist mindset, we don’t have time to protect other people. Small changes, like volunteering at the food bank or the community garden, foster advocacy.

ESQ: In the chapter about office technologies, a source at Twitter says, “We don't want to be remote first or office first. We want to level the field. And that means we have to stop doing some things in the office that we do well, like the current way we do food service. We’re trying to disincentivize some parts of that experience that lull you into the office; we’re trying to take away some of that ease.” Their model seems at once radical and terribly obvious. What do you make of it?

CW: What they’re doing might fail, but I appreciate the intentionality. I love the fact that they're trying things. I have a lot of issues with tech companies in general, but in this case, I think that they're doing the right thing. They're saying, "We might have messed this up, but we'll fix it."

AHP: Companies like Microsoft and Amazon have been listening to feedback from workers. Microsoft is a very traditional “butts in seats” company, and now, they’re becoming a hybrid workplace. Sometimes I hesitate to point to tech companies in terms of what the future is going to be, because they mess it up a lot. They also promote a real addiction to work and obsession with work. Their campuses and how they promote a total envelopment of your life by work are problems. But at the same time, what happens at tech companies trickles down.

CW: There’s a classic example of Google creating a different way of management. They had this idea about psychological safety—feeling safe to express certain ideas. You can think it's BS or you can love it, but it became a business school case study. Then all sorts of fusty old companies adopted it. That’s what's going to happen here. Businesses can fight the remote future tooth and nail and demand butts in seats; maybe that works in the short term, but eventually, you’re going to pay a bunch of overpriced McKinsey consultants to come in and tell you exactly what a lot of these other companies are doing right now. You’re going to be five to seven years behind, and it's going to cost you hundreds of thousands of dollars in consulting fees. Make your choice.

ESQ: This is all great for Twitter and the companies who go on to emulate them, but as you point out, “The true benefits of remote work will only arrive if we codify them as with real policy—the sort that makes them tenable beyond the world of knowledge work.” What polices would you like to see enacted to make these reforms accessible for all?

AHP: The childcare crisis is a huge part of this. We’ve taken a giant step back in terms of gender equity in the workplace. There are so many women who have permanently left the workforce, and the way to get them back is to provide reliable childcare. We can't have an ad hoc solution to that; it’s not enough. It has to be federal funding that makes childcare accessible and affordable for everyone. We also have to turn childcare jobs into good jobs—sustainable jobs that aren't paying below the poverty line. Some people think of this as a completely separate issue than working from home, but they overlap. Privileged people are finding solutions to this. They pay more; they figure it out. But so many people are struggling. We have to come up with a robust solution in order to actually move forward with any equity in the workplace. Otherwise, we're going to have a workforce that looks like 1960.

CW: What I’ve realized in reporting this book is that any major societal problem is connected to 500 others. We see that with the issue of work. If people feel they can lose their job at any moment, that instills a mentality where it doesn't matter how many perks or benefits employees have; people are going to feel the need to grind themselves into a pulp for their jobs, because they're terrified. That has to change. The levers there are policy-based and structural. We can spend all day saying, "This is how you should conceive of your job and decenter work from your life.” But the reality is, if we don't give people a safety net, it's going to be incredibly hard for them to adopt that mentality.

ESQ: You can set all these boundaries for yourself, but when someone is willing to sublimate themselves more than you, your boundaries inevitably collapse. If the policy isn’t there, we’re all just racing one another to the bottom.

AHP: Totally. The hard thing within an ingrained ideology of individualism is that it’s so difficult to dismantle. But there’s historical proof that we’ve oscillated between these poles of individualism and collectivism. One of the experts we cite in the book thinks we’re ready to seesaw again.

CW: It’s already happening, both in the knowledge work sector and the service sector. Look at the way Gen Z considers careerism to be a raw deal. All of that is moving toward something, which could very well be a more collectivist mindset. But you can only do so much. You can only quit your job to send a message to your bosses for so long; then you need a job. So what do we do in this moment? That’s why we felt a sense of emergency about writing this book. A window is opening, but we don’t know how long it will remain open.

AHP: But I do think the window's lasted longer than we anticipated, simply because the pandemic has continued to extend. You remember, in the summer post-vaccine, there was this sense that things would return to normal soon. Then Delta changed everything, and who knows what’s going to happen now, I think it's just further proof that we need to continue pushing on these ideas.

CW: Something has broken open. For decades, people said, "Hey, can I pick Friday and work from home?" Or, “I have a sick mother. I need to fly to where she is and work from home." Corporations would say, "If you do this, everything will fall apart. Your work will be bad, and we will suffer. The office is what’s holding together the productive fabric of America." Then we were forced to work remotely. Obviously it was a bad situation, but people were productive. Things didn't change all that much. All these people have woken up and realized, "If that was bullshit, what else is bullshit?" What else have we been told that’s just totally wrong, or just self-interest framed as business acumen? That's the thing that's broken in a lot of workers’ minds. They think, "I don't trust you at all, based on how you made me live my life, and what I had to sacrifice for you." That’s profound. That will last, even if we're all back in the office, chained to our desks. That’s going to last.

ESQ: Has reporting this book and spending so much time with these ideas changed the way you approach work?

AHP: In a lot of ways, this book is a spiritual follow-up to Can’t Even. They interlock in terms of trying to figure out why work is broken and how to fix that. I've become even more keyed into seeking ways to distance myself from work. How can I force myself to leave the laptop? One of those off-ramps, for me, is gardening. The other is hanging out with my friends’ kids. During the pandemic, after we finished writing the book, we actually made a move to a tiny island of 900 people off the coast of Washington. We moved here because we’ve developed community here over the course of the pandemic. We wanted to practice what we preach in the final chapter about community, which is what we’re trying to do now.

CW: At one point in my life, I left what was essentially my dream job. I feel like I've reoriented all of my priorities, but it’s an ongoing struggle. That's one thing I want to make clear: we don't have it all figured out. I think about it very similarly to therapy or exercise. You don’t wake up after two days of therapy and say, “I’m done.” You don’t finish six weeks of workouts and say, "That's it. No need to work out again. I did it." It's a constant process of maintenance. It’s about developing patterns and slowly changing your relationship to something—how you see it, how you treat it, how you prioritize it. That maintenance never gets easier when you’ve spent your entire life thinking one way about work, and how work is tied to your self-worth and value. I struggle every day with this. The only thing I can do is be intentional.

Yesterday I had a lot of work to do, and we also had to go out and run errands. 2016 Charlie would have canceled all those things, done the work, and felt subsumed by it. But I didn't do that—I chose to run the errands. Certain things didn’t get done, and I had to apologize for that, but I have to be a person. If I destroy those barriers I've set for myself, then I'm just going to revert back to the old way, and the old way wasn't good.

You Might Also Like