A thousand kids and counselors went to summer camp in Maine. Only 3 got the coronavirus.

WASHINGTON — Out of 1,022 people who either attended or worked at several overnight summer camps in Maine that implemented measures to prevent the spread of the coronavirus, only three tested positive for it, a new study says. And those three cases did not result in secondary infections because proper measures were taken.

The encouraging news emerged from a new study the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention made public on Wednesday. It comes on the heels of another CDC study, released last week, that showed that after childcare centers in Rhode Island opened in June, there were few infections and almost no secondary transmission throughout the surrounding community.

Together, the two studies seem to offer promise. “These camps did it right. They followed the basic public health measures,” said Dr. Ashish Jha, a Harvard epidemiologist.

Those measures included “face coverings, enhanced hygiene measures, enhanced cleaning and disinfecting, maximal outdoor programming, and early and rapid identification of infection and isolation,” according to the new study’s lead author, Dr. Laura Blaisdell, a pediatrician at the Maine Medical Center who serves as a medical adviser to the American Camp Association.

CDC Director Robert Redfield celebrated the results. “Using a combination of proven public health strategies to slow the spread of COVID-19,” he said in a statement, “campers and staff were able to enjoy a traditional summer pastime amid a global pandemic.”

Jha contrasted the Maine approach with that of a Georgia camp that was more lax — it did not require masks or adequately ventilate buildings — and consequently became the site of a coronavirus outbreak earlier this summer. That experience called into question the much-longed-for resumption of other everyday activities, including schooling.

The Maine study was especially encouraging for colleges, Jha explained, since in both camps and colleges, young people live and play in close quarters. “The biggest thing here is they were aggressive on entry screening,” he said. “It’s really smart, and it works.”

The new CDC study followed attendees at summer camps in Maine between June and August. “Approximately 1 week after camp arrival, all 1,006 attendees without a previous diagnosis of COVID-19 were tested, and three asymptomatic cases were identified,” the study says. “Following isolation of these persons and quarantine of their contacts, no secondary transmission of SARS-CoV-2 occurred.” (SARS-CoV-2 is the official international designation for the pathogen.)

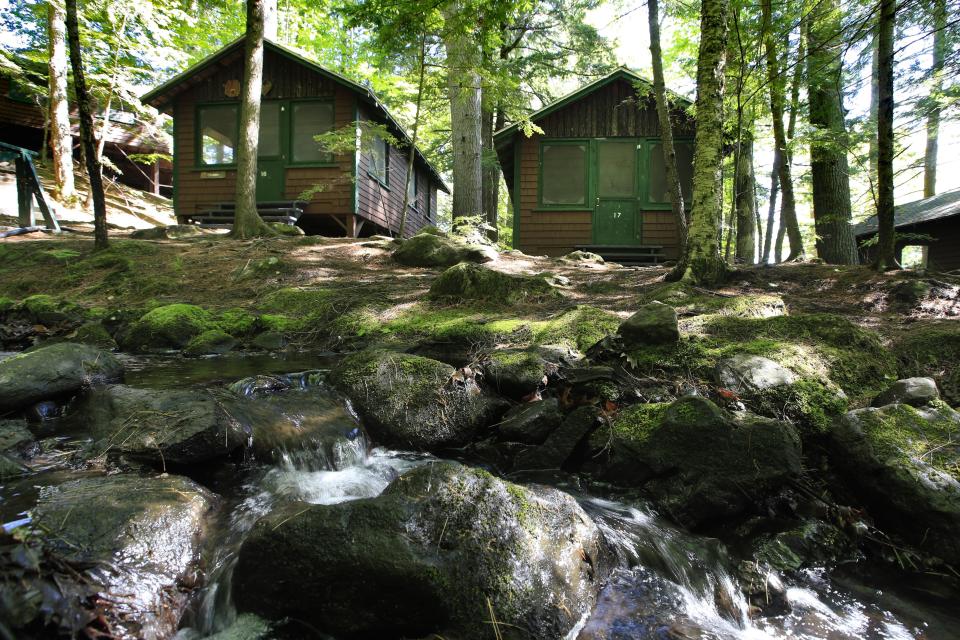

The camps took the kinds of measures that would be difficult to undertake in a large city, or even a suburb. “Camps and schools are not the same,” said Blaisdell, who has been volunteering in a medical capacity at her sons’ camp for 20 years. At the same time, the camps hosted attendees from 41 states and six countries, as well as one U.S. territory.

Some came from coronavirus hot spots, including Texas and Florida. A college could encounter a similarly challenging demographic distribution from its incoming students.

Attendees and their families were advised to drive to camp. Once they arrived, campers were asked to stay within their new cohorts for two weeks and not mix with other children. They were routinely monitored for symptoms, with daily temperature checks, and diagnostic tests administered between every four and nine days.

“No attendees declined testing,” the CDC study says, a subtle reminder that public health measures mean little if people refuse to adhere to them. The results came back two or three days later. Across the country, people continue to report waiting as long as two weeks to learn the results of their coronavirus tests.

Two adults and one child eventually tested positive, despite showing no symptoms.

A new CDC guidance says that people who do not show coronavirus symptoms do not always need diagnostic tests. But people without symptoms can still spread the disease. Dr. Eric Feigl-Ding, an epidemiologist, said the Maine approach showed what a “wrong-headed move” the CDC was making by dropping the guidance to test asymptomatic people.

If the camps had not done such testing, they would not have found the three people infected with the virus. Those people could then have spread the disease to other campers.

Blaisdell described to Yahoo News what happened once those positive tests were returned: The three sickened individuals were isolated, while their respective cohorts were moved into what she described as a “shadow camp,” apart from other attendees. They were still able to take part in camp activities, but without potentially becoming transmitters of the virus. They were also regularly tested.

The strategy proved successful. “No cohort members received a positive test result, and all were released from quarantine on day 8 after the asymptomatic camper’s positive test result,” the CDC study reported. “No secondary transmission was identified.”

Blaisdell said that keeping children in small, well-defined groups was critical to the camps’ success. “Cohorting allowed us to decrease spread by kids in small, stable relationships.”

The study she and four other authors from outside Maine published Wednesday through the CDC describes how “stable, small, segregated cohorts allowed camps to isolate and quarantine a wide age range of younger attendees with potential COVID-19 symptoms and exposures while continuing camp operations in other cohorts.”

Classrooms are natural cohorts. So are some college arrangements, such as Greek-letter organizations and special-affiliation houses. At the same time, both schools and colleges are bound to be subject to much more movement throughout the surrounding community than an isolated camp in rural Maine.

“Nobody can promise a COVID-free environment,” Blaisdell told Yahoo News, but by enforcing a “culture of compliance,” the camps were able to have a relatively normal summer.

“We did do singing around the campfire,” she said, adding a caveat that can be attached to virtually any human activity in 2020: “It looked different this year.”

_____

Read more from Yahoo News:

You don't need the U.S. Postal Service to deliver your mail-in ballot

'I trusted them.' Some 'Build the Wall' donors feel cheated by Bannon. Some don't care.

Exclusive: DHS warns of fake election websites potentially tied to criminals, foreign actors

Oleandrin, touted as COVID-19 cure, has no scientific support