A history of selling out the Kurds, people with 'no friends but the mountains'

As the skies over northeastern Syria blackened with smoke this week, as Turkish warplanes swooped down and gunfire and shelling resumed in what had briefly been an oasis of relative peace in the region, the world recognized what 36 million Kurds already knew: They had been betrayed, not for the first time, by their putative allies. In this case, the United States.

It has been a constant theme in the history of the Kurds, an ethnic group indigenous to parts of Iran, Iraq, Syria and Turkey. The quest for their own country where they could freely speak their own language, a right denied them for most of the 20th century, has come to define the Kurds, along with the broken promises of world powers that are happy to enlist the tough mountain people to fight their battles, but in the end find a reason to cut a deal with the national governments that have standing armies — and oil.

It was a decision by President Trump on Sunday, after he spoke with Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan but without consulting either the Pentagon or the State Department, that paved the way for the latest betrayal. In withdrawing a token force of American troops from an area of northeastern Syria, Trump opened the door for Erdogan’s “Operation Peace Spring” to create a 300-mile “safe zone” — safe for Turkey, that is — along the Syrian border and rid it of what Erdogan described as a Kurdish “terror army.”

That army was the U.S.-backed and Kurdish-led militia known as the Syrian Democratic Forces, which had borne the brunt of the war to destroy the Islamic State group’s caliphate, a prime goal of American policy and an achievement Trump frequently claims as a personal victory. Critics, including many Republicans, denounced the move as both a moral and political debacle, a betrayal of allies who had fought alongside American troops, a humanitarian disaster in the making, and an opening for ISIS to regroup in the growing power vacuum.

A resolution in the United Nations Security Council condemning the Turkish invasion, supported by most European nations, was opposed by the United States — and Russia.

As Timothy Noah wrote in 2003 for Slate, after Kurdish fighters helped the U.S. topple Saddam Hussein in the expectation of finally winning an independent Kurdistan, “For Kurds, getting screwed is a tradition.”

The history of betrayal, and of enmity with Turkey, begins a century ago with Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, who created the modern Turkish state out of the ruins of the Ottoman Empire. For millennia, Kurds — traditionally farmers and herders skilled in carpet weaving, copper working and fighting on horseback (like the Kurdish warrior hero Saladin) — lived in the contiguous mountain regions of what today are Turkey, Iraq, Syria and Iran. Estimated to be some 36 million strong, most of whom are Sunni Muslim, they’re united by their Kurdish language — similar to Farsi in Iran — and a hope for their own country, an idea first officially dangled in the country-building era following World War I.

While the Allies’ 1920 Treaty of Sèvres threw in mention of a land for the Kurds, the charismatic Turkish field marshal, Atatürk, whom Kurds initially supported, had very different ideas when he took power in the new Republic of Turkey in 1923.

Refusing to acknowledge “Kurdistan” or any of the myriad ethnic groups and languages across his land, Atatürk instead imposed Turkification across the new republic. All inhabitants had to change their names, modernize their dress — he outlawed wearing of the turban and the fez — and learn a new language, this one written in Latinized letters. Religion was deemphasized, education was mandatory, soon women could vote.

Only one language could be spoken in public, one culture preserved, and that was Turkish, his version of it. Those who didn’t embrace his vision encountered his army.

Through the 1920s and 1930s, Atatürk’s forces slaughtered hundreds of thousands of those who rebelled against his plans, including Armenians and Kurds — whom Atatürk called “Mountain Turks,” having banned the word “Kurd” from the new Turkish vocabulary. During those same postwar decades, Kurds rebelled in Iraq, where the British had promised them their own land in the province of Mosul, and where their efforts were likewise violently suppressed.

But after decades of violent uprisings, the Kurds’ quest for their own land finally materialized after World War II, a war that Turkey (and the Kurds) largely steered clear of, which Trump noted in observing that the Kurds didn’t fight alongside America in Normandy.

On Jan. 22, 1946, with backing from the Soviet Union, the Kurdish Republic of Mahabad was created in a finger of land in northwestern Iran that the Red Army had occupied. Kurdish printing presses were set up and schools opened, teaching classes in Kurdish, the first seeds planted in Kurdish soil. By the end of the year, however, the Soviets had pulled out and the Iranian shah had reclaimed Mahabad, promising more autonomy but instead executing its leaders and ending its independence.

During the 1980s, the dream reemerged. A young Turkish Kurd, Abdullah Öcalan, rallied thousands of Kurds to fight for an independent Kurdistan carved out of part of Turkey. The guerrilla Kurdistan Workers’ Party, or PKK, declared war on the Turkish government and began attacking military installations and government facilities. That guerrilla war continues to this day, despite occasional cease-fires, thus far claiming 40,000 lives on both sides. New PKK offshoots, such as the Kurdistan Freedom Hawks, or TAK, target civilian facilities as well, such as Istanbul’s football stadium, lending plausibility to Erdogan’s denunciation of a Kurdish “terror army.”

In the Iran-Iraq War, Iran, hoping to weaken its enemy, supported Kurds fighting Saddam Hussein. Iraq expelled thousands of Kurds to Iran, but Iran sent them back in 1984. Four years later, Iranian forces helped Kurds capture the northern Iraqi city of Halabja. Saddam responded with a chemical attack — the event President George H.W. Bush referred to when he denounced Hussein’s “gassing of his own people.”

In 1991, when Bush urged the Kurds in northern Iraq and the Shiites in the south “to take matters into their own hands, to force Saddam Hussein, the dictator, to step aside,” they listened and mounted a short-lived rebellion that Saddam put down through airpower, defying the no-fly zones the U.S. had proclaimed.

When the second President Bush announced in 2003 that the U.S. was returning to take down Saddam, the Kurds in the north again answered the call to help — and again were disappointed when the U.N. resolution establishing a post-Saddam Iraq ignored their request for an independent Kurdistan.

The new Iraqi constitution, however, gave Kurds limited power and autonomy as part of the Kurdish Regional Government, and a makeshift Kurdistan began functioning in the north, based in oil-rich Kirkuk. In 2014 the Kurds battled ISIS for control of the city, and joined the U.S. in the five-year fight against the caliphate.

Kurds made strides in Turkey as well: The Peoples’ Democratic Party, a pro-Kurd political party, became the country’s third-most popular party and took seats in Parliament.

In 2017 Kurds in Iraq voted to secede, a movement quashed by the central government in Baghdad.

However, as hopes dimmed in Iraq, they brightened in Syria. A great swath of northeastern Syria, known as Rojava — “the land where the sun sets” — was turning out to be a democratic experiment in war-torn Syria. Home to millions of Kurds, the autonomous region, which abuts the Turkish border, was beginning to function as a de facto Kurdistan. Life was relatively peaceful under the watch of the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces, under the implicit protection of American troops.

That changed on Sunday, when after a chat with Erdogan, Trump agreed to turn his back on his Kurdish allies. And while Sen. Lindsey Graham implored the nation to “pray for our Kurdish allies who have been shamelessly abandoned by the Trump administration” and the president absurdly complained that the Kurds hadn’t helped America in World War II, the Kurds were once again looking for refuge, invoking their well-worn adage: “We have no friends but the mountains.”

_____

Download the Yahoo News app to customize your experience.

Read more from Yahoo News:

Greta Thunberg: Powerful men ‘want to silence’ young climate activists

Driven from Central America by gangs and finding refuge in Kentucky: One woman’s story

‘I talk about power because you’re not supposed to’: Why Stacey Abrams still wants to be president

Nation’s intelligence officers are resigned to serving a president who doesn’t trust them

Before Black Lives Matter: Exhibition pays tribute to an earlier NYPD killing of unarmed black man

360: U.S. pulls support for Syrian Kurds: What happens next?

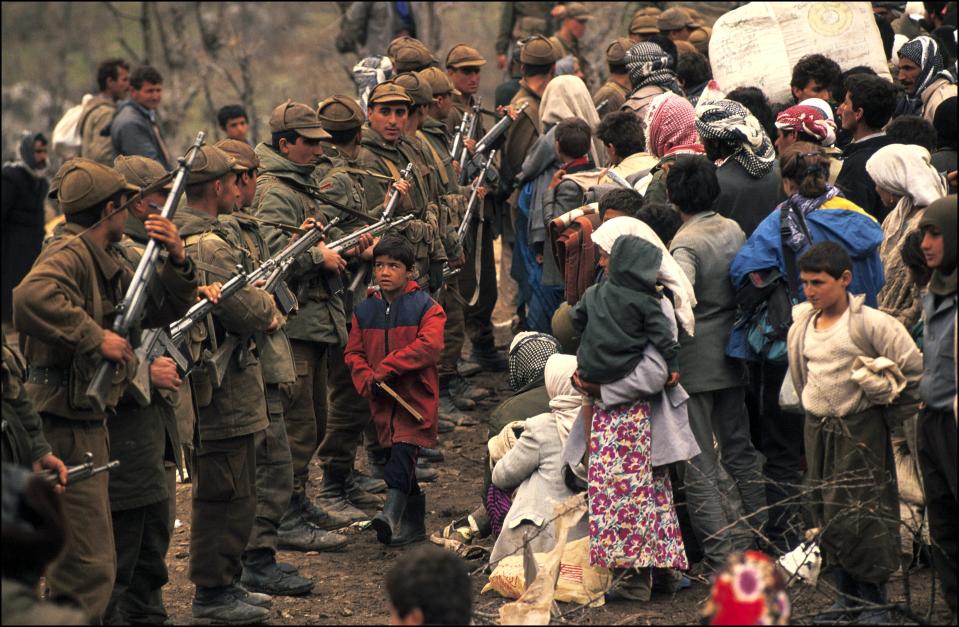

PHOTOS: Turkey presses Syrian assault as thousands flee the fighting