85 years ago, FDR saved American writers. Could it ever happen again?

Kristen Hare is a reporter with a grim beat in the time of COVID. She tallies the carnage of newspaper layoffs for the Poynter Foundation. “Every day I add them,” she says, “and the next day it starts all over again.”

To which millions of Americans right now would be more than entitled to say: Boohoo. As did skeptical Americans during the Great Depression when, 85 years ago today, Franklin Roosevelt signed the Works Progress Administration into existence. But today, we look back on the WPA — and the Federal Writers Project, which FDR authorized 10 weeks later — as among the wisest things the United States ever did.

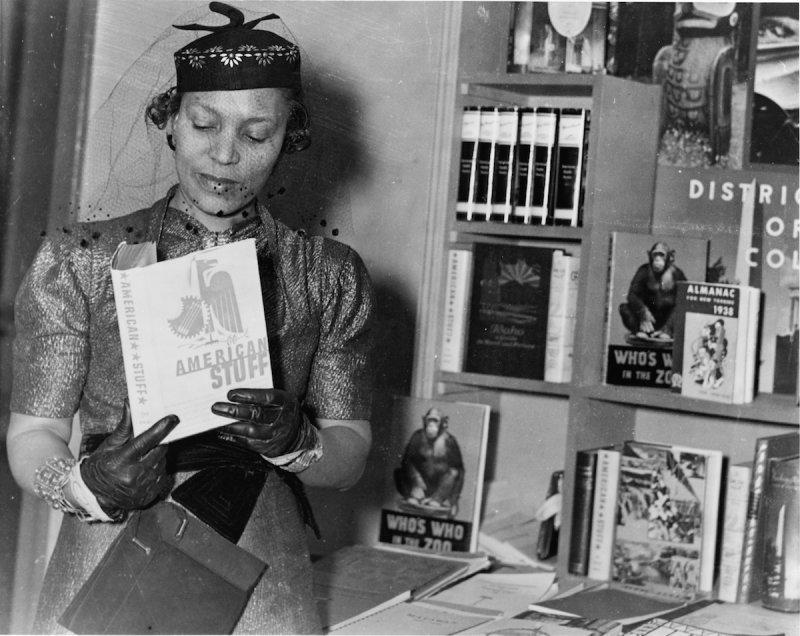

If the Writers Project had only ever kept young, broke writers like Zora Neale Hurston, Kenneth Rexroth and John Cheever off the dole, it would have been enough. Picture Saul Bellow, Studs Terkel, Nelson Algren and Richard Wright around the same Chicago office coffee urn, griping about going underappreciated. Years later they would be honored with a Nobel, a Pulitzer, a National Book Award and a U.S. postage stamp, respectively.

In addition to producing wonderfully written guidebooks to all 48 states, many American cities and more, along with invaluable oral histories, the project helped make writers out of people who otherwise might never have had the chance. Yet its riches don’t just belong to English majors or historians, or even all the shunpike travelers who, to this day, refuse to leave home without at least one state guide in the glove compartment. No, the Federal Writers Project’s greatest gift lay in introducing Americans to their multifarious, astonishing, broken country.

The program “made writers go out into the world,” says Dagoberto Gilb, the award-winning L.A.-born novelist. They learned “what unseen working people who might not read much think and say” — people who “told beautiful human stories to writers who recorded them. Like fables.”

Don’t take Gilb’s word for it. John Steinbeck called the American Guides “the most comprehensive account of the United States ever got together.” Thomas Pynchon — nobody’s idea of an easy grader — wrote that the guides “make instructive and pleasurable reading. In fact, there is some stuff in the [guide to the Berkshires] so good, so rich in detail and deep in feeling, that even I was ashamed to steal from it.”

There is one living writer whose evangelical belief in the lasting lessons of the FWP beggars even my own. Jason Boog, the L.A. correspondent for Publishers Weekly, will soon publish an eerily timely new book, “The Deep End: The Literary Scene in the Great Depression and Today.”

“The American Guides,” he says, “captured all sorts of cultural works that we could have forgotten: dance steps in Harlem, the early efforts of union organizers in Hollywood and the locations of Hooverville tent cities around Manhattan. As we go through our own crisis … I think a FWP in the 21st century could raise up the voices of people most directly affected by this disaster.”

As we approach Depression-era unemployment levels, could another Project come to pass? Gray Brechin, the UC Berkeley geographer who founded the Living New Deal project — an indispensable online map of every last WPA building, mural and bridge in America — isn‘t holding his breath:

“I don’t see anything like a renewed, let alone expanded FWP in the offing. That we had one once was a mark of both the ingenuity and compassion of the Roosevelt years.”

The natural suspects to pull off a new Writers Project would be the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities. In March they received $75 million apiece under the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security Act. (For five years, I led literary initiatives for the NEA out of what’s now a 7th-floor suite in the Trump Hotel.)

Reached at her office, NEA Chair Mary Anne Carter sounds as busy as a battlefield surgeon. “Helping arts and literary organizations at this time really means helping them survive,” she says. “We hear talk of a Phase 4 bill and the Congress has asked us various questions, but any new programs ... would have to be written into the legislation.”

One of Carter’s predecessors, Dana Gioia, points to a vastly different environment. “When [the FWP] began 85 years ago, the literary world was entirely for profit — newspapers, magazines, and publishers — and the number of writers was smaller,” he says. “There are hundreds of thousands of writers [today], probably more than auto workers.”

If it were up to him, Gioia “would recommend that the NEA expand programs such as the Big Read to hundreds of cities across the U.S. to keep readers, libraries and bookstores engaged. They are the necessary infrastructure for literature.”

My old NEA colleague Jon Peede is now chair of the NEH. He says scholars and cultural centers are already documenting the pandemic, “but I don’t expect the U.S. government to formally organize these efforts, which have sprung up spontaneously. Our federal cultural agencies should seek ways to make catalytic investments in these efforts.”

Should any trade publisher ever want to help revive the Project, their first call should be to Matt Weiland. Vice president and senior editor of W.W. Norton, the only major employee-owned imprint in Manhattan, Weiland independently published “A New Deal for New York” in the wake of the 9/11 attacks. He also co-edited “State by State: A Panoramic Portrait of America,” a collection of essays by Gilb, Susan Orlean and 48 others consciously modeled on the WPA Guides.

“I would relish a revitalized Federal Writers Project, of any scale, for our time,” says Weiland. “Vast portions of our country remain shockingly underdescribed, and vast numbers of its citizen-writers remain underemployed. What better time, what fitter moment to engage loads of them in meaningful work and create a detailed and lasting portrait of America in (let us hope) the wake of the pandemic.”

David A. Taylor, who co-wrote “Soul of a People: Writing America’s Story,” a moving documentary on the FWP, envisions a more modern version taking hold.

“I don't see writers making guide books but a range of narrative products documenting this moment — podcasts, photo essays, oral histories,” says Taylor. “We could try different models like start-ups with an eye for what might come out of this crisis. … But it would likely have more private and philanthropic partners.”

I reached out to all the partners Taylor spitballed — the Gates Foundation, 826 National, ProPublica, the American Journalism Project and others. Only Steven Waldman sounded jazzed right away. He is president and co-founder of Report for America, a national program that places reporters into local newsrooms, with help from places like Facebook, Google and the Annenberg Foundation.

Just this year in California, Report for America subsidized the creation of about 20 journalism jobs from the Long Beach Post to Spectrum News 1. Waldman’s idea for a new FWP was the most concrete I’d heard yet: Start with existing programs like AmeriCorps, “itself inspired by a bit of CCC [California Conservation Corps] and WPA with a touch of Peace Corps thrown in.” The 27-year-old program could scale up Waldman’s efforts — 225 reporters placed in the field this year — all the way up to 5,000.

Waldman had bogarted my crack pipe! So I took a deep breath and fired off an email to William Randolph Hearst III, the publisher of Alta magazine (to which I’ve contributed) and chairman of the board of his namesake media giant. His publisher grandfather hated the WPA even more than he hated “Citizen Kane,” Orson Welles’ pitiless fictionalization, but Will Hearst is different. He’s exactly the guy you hope you’d be if you were an heir to one of the largest media empires in the world.

"I am a huge believer in the Federal Writers Project,” Hearst wrote back. “And it’s on my bucket list to collect the WPA State Guides … I would be pleased to help.”

It was good to hear, but there's help and there's help. Nobody, not even a major philanthropist, would attempt such an outlandish venture without partners. But could a few individual and corporate foundations, coupled with some “catalytic investment” from a federal agency and a few thousand reporters, somehow cobble together a new kind of Writers Project?

To put it gently, 2020 is not 1935. The notion that a consortium of individuals can coordinate on anything like the level that a strong, organized federal government seems difficult to imagine. The sense of shared national endeavor that midwifed the Writers Project feels like a relic from another millennium. In a country and a time as divided as this one, the Writers Project threatens to sound like a bedtime story — just another of Dagoberto Gilb’s “beautiful fables.”

But please, please, won’t somebody tell it again?

Kipen is a former director of national reading initiatives for the NEA. He’s written introductions for reissues of four WPA Guides and founded the lending library and podcast Libros Schmibros.