37 Years Later, We're Still Living the Nightmare of 'White Noise'

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through the links below."

They called the first nuclear bomb “Gadget,” and it detonated north of the beautiful dunes of White Sands National Monument at 5:30 a.m. on July 16, 1945, sending a cloud 38,000 feet into the air. A half-mile wide crater formed where the bomb exploded. The intense heat caused the sand beneath the bomb to turn into a new, glass-like material. An awesome sight. A terrible thing. The Trinity test was a success. The world’s most deadly killing device was born. Less than a month later, another bomb called “Little Boys” detonated over Hiroshima, Japan, destroying the city. Three days later, “Fat Man” obliterated Nagasaki. Nuclear war arrived, and we’ve never been able to shake it.

The feeling of unease that rippled through the culture after the atomic bomb was invented had an indelible influence on Don DeLillo, one of America’s great novelists of the 20th century. A writer who straddles Pynchonesque conspiracies with a good helping of existential dread and hope, he has a gift for dialogue reminiscent of an early Wes Anderson movie (or better yet, Anderson’s early movies have the rat-a-tat dialogue and set pieces of a DeLillo novel).

“I think my work is influenced by the fact that we're living in dangerous times,” DeLillo told The Chicago Tribune in 2012. "If I could put it in a sentence, in fact, my work is about just that: living in dangerous times.”

DeLillo certainly lived through dangerous times. Born in 1936 in the Bronx, he saw everything that came with being born three years before the start of World War II. Later, the assassination of President John F. Kennedy Jr. solidified that feeling of precarity. The events of that day left an indelible mark on the author. He was 27 years old at the time, eight years out from publishing his first novel, and 21 years from becoming a household name with the National Book Award-winning White Noise.

"I don't think my books could have been written in the world that existed before the Kennedy assassination. And I think that some of the darkness in my work is a direct result of the confusion and psychic chaos and the sense of randomness that ensued from that moment in Dallas,” DeLillo told The New York Times in 1991. “It's conceivable that this made me the writer I am—for better or for worse."

His writing, specifically Underworld and Libra, seems to grow from those moments. His work centers on American life after those events, bleeding into a refined postmodernism that rejects universal truth and instead examines our desire to consume.

Though the dangerous times have evolved from nuclear war to terrorism to right-wing extremists and mass shootings at schools, the dread of being washing away by the noise that surrounds us remains—the advertising, the radio waves, the blue and white lights, the hum of the refrigerator, and now the draw of the smartphone and the Internet. DeLillo’s stories have evolved with society, able to stand in at times when they could or should feel outdated, but none feel more poignant than White Noise, now adapted for Netflix by Noah Baumbach.

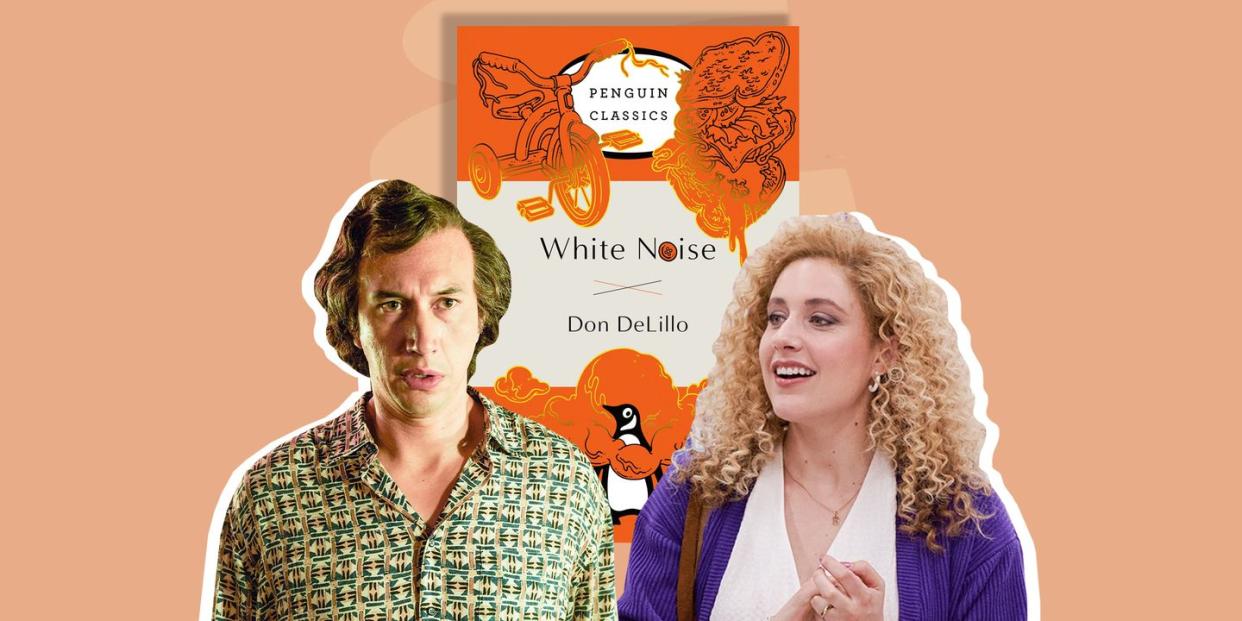

White Noise

amazon.com

$15.99

amazon.comIt’s been 37 years since Don DeLillo wrote White Noise, the seminal postmodern novel about a Hitler professor, his family, an airborne toxic event, and how people deal (or don’t deal) with death. The novel, like all DeLillo novels, loads each sentence and word with meaning. It feels, at times, like a jazz record, free-flowing from one conversation to the next, with off-beats tossed in, but each twist and turn never meandering far from the story. The author told the Chicago Tribune that he writes each paragraph on a separate piece of paper, giving each one its own life and weight. So why does a 37-year-old book feel so relevant today? And why is it the right time to finally attempt a screen adaptation? Like so much of DeLillo’s work, the book is a product of its time, but it also tries to distance itself from that moment by encapsulating more than a moment. The sounds that surround us may be white noise—all the marketing, all the technology humming—but it’s also something more. It’s the sound of death.

In the 1980s, DeLillo could never have dreamed where the world would end up, but his universal truths still hold. As we’re bombarded with emails, texts, and social media posts, the book is as relevant, if not more, than it ever was. All of us search for meaning as we experience daily FOMO on our phones, wishing for another life, one promised to us by advertising agencies and politicians. For that, the book is a perfect satire of the world we still live in.

White Noise centers on Jack Gladney, who is also the narrator, and his family. Gladney is a professor at a small Midwestern liberal arts college where the faculty wear robes around campus. He originated the field of Hitler studies, and even though he will host a Hitler conference, he can’t speak German. The simmering studies of the college allow Gladney the time to interact with his colleague Murray, who teaches a class on the cinema of car crashes and develops a field of study on Elvis that's not so dissimilar from Gladney’s Hitler work. (One must imagine that Murray can’t dance like Elvis.) The pair often run into each other at the grocery store, where Murray is always purchasing items from the generic brand aisle, which comes off in DeLillo’s rendering of the world as soulless and lacking any color or advertisement. Murray is the true sounding board for Gladney as he tries to unravel the mysteries of his life and his family—namely, his and his wife’s fears of dying.

Gladney’s family life is the focus of the book. He lives with third wife Babette and their brood of four kids from their previous marriages. The children largely manage themselves, except for the youngest, Wilder, a two-year-old. The Gladneys move from room to room, talking incessantly, watching television, and all obsessing over something. Babette teaches posture to local elders and reads the tabloids to a blind man, but it’s a bottle of a secret medicine labeled Dylar that sets the book in motion. (Well, alongside the chemical spill at the train yard that forces everyone in their ideal town to flee their homes so as not to be exposed to a large, dense toxic cloud.) Gladney is exposed to the cloud and the readings aren’t good, even if he doesn’t know what they mean: he’s going to die. Before, the couple’s conversations about death feel innocuous. They love one another and don’t want it to end, but they realize that it will, and try to make their mortality feel less important.

“The question comes up from time to time, like where are the car keys,” DeLillo writes. “It ends a sentence, prolongs a glance between us. I wonder if the thought itself is part of the nature of physical love, a reverse Darwinism that awards sadness and fear to the survivor. Or is it some inert element in the air we breathe, a rare thing like neon, with a melting point, and atomic weight?”

There’s no fear of impending doom early in the novel. When a smoke alarm goes off, no one budges; they just finish their lunch. Even when a toxic chemical is found at the children’s school, supposedly killing a “masked and Mylex-suited” man, no one seems to mind. They’re all wrapped up in life, in watching television throughout the day, and at least once together as a family. It takes bullhorns and warnings for the family to leave their home as the toxic cloud rises. This can’t happen to us.

Only Heinrich, Jack’s son, is worried. He bunkers in the attic and follows the chatter, watching the billowing cloud at the train station grow. The Gladneys hastily pack and head out, driving past furniture stores and gas stations, where they need to stop. The parents turn the radio down for fear that their children will start to show the rumored symptoms of toxic chemicals.

Gladney starts to wonder about death in a more concrete way. Eventually, he uncovers the truth about Dylar and what it did or does for Babette. The pills ease her fear of death, but also make her forget things. The habit stole part of her memory, and when she stops taking Dylar, she begins to stare aimlessly out the window and never changes out of her sweatsuit. But for Jack, the idea of forgetting about death becomes an obsession. He needs it. He will do anything to obtain it.

White Noise lives in a place that is all too familiar today. If the televisions were replaced with smartphones and the tabloids with QAnon or 4Chan message boards, then the novel would read as contemporary. There are the conspiracy theories running riot underneath the text. There are the simulated doomsday scenarios in which Jack’s daughter participates. There’s the unknown cloud of a dangerous vapor whispering in their ears, its impact on the human body unknown.

Baumbach told The New York Times Magazine that he picked the book up in 2019. He’d read it in high school, but for some reason, he decided to reread it as he promoted his previous Netflix movie, Marriage Story, going from awards show to awards show. Then COVID came knocking, and quickly everyone was thrown into the feeling that at any moment, it could be them. Death could arrive while we walked down the aisles of the grocery store, afraid to go near anyone, following the arrows on the floor, staying in our lanes, wiping the bags down, stripping off our clothes and showering as soon as we got home.

What did we do? We found solace in technology and our everyday needs. We bought Pelotons, gaming systems, backyard movie set-ups, new computers. We baked bread and had Zoom parties. We bonded over a nostalgic documentary about Michael Jordan, who also happens to be the greatest symbol of the power of advertising ever to walk this earth, produced by Michael Jordan.

And as quickly as it began, it ended. We moved back to life. The “new-normal” arrived. For most of us, we understood the risks of going out and getting sick. We knew what it meant. We accepted it. (Others kept reading the equivalent of the tabloids.) For some, the fear of “what if” still won’t quit. For all of us, the fear simmers somewhere underneath. We saw our own mortality.

In White Noise, the fear of death sends Jack spiraling. He can’t escape it. He needs the medicine. He needs the little white pills. When they go missing, Babette falls apart in a different way—she retreats inside herself, giving up. Jack goes on fighting. He chases down leads and finds some Dylar, but he makes a near-fatal mistake and lands himself in a hospital full of nuns in a nearby town’s old German neighborhood. They speak German, and of course, he can’t understand them. He questions a nun about her beliefs. Does she believe in Heaven? No. She’s a nurse and her job is to take care of the sick. “It is for others. Not for us,” she says. Everyone else needs them to believe.

“All the others,” the nun says. “The others who spend their lives believing that we still believe. It is our task in the world to believe things no one else takes seriously. To abandon such beliefs completely, the human race would die. This is why we are here. A tiny minority. To embody old things, old beliefs. The devil, the angels, heaven, hell. If we did not pretend to believe these things, the world would collapse.”

What comes to pass for Jack is that the world won’t end. Death is inevitable. For us, that’s true, too. I stay awake at night thinking about death. I’ve hated birthdays for as long as I can remember because it means the people I love are getting a year closer to death. But I also find comfort in moments. Life is filled with them. Life isn’t worth living without death on the other end. Its fleeting nature is what makes it meaningful.

Early in the book, Jack tells Babette, “Maybe there is not death as we know it. Just documents changing hands.” Maybe death really is that simple. Maybe there’s nothing to fear in the long run because there is no escaping it. Maybe it is just that simple: Documents changing hands. We feel nothing after that. Instead, the people we leave behind have our life to pick up and put away. All the paperwork when someone dies is its own kind of misery. But even before we die, our life is a pile of documents. We have our photos, emails, and texts. It’s all stored in the cloud that lives and breathes above us, chasing us even as we try to escape. Eventually we give in and forget it’s there until we’re reminded it lingers when we’re told there will be an update. Our own personal art projects. And what is art but something to reflect back to us the beauty, pain, or absurdity of the world around us? What is it other than white noise in a crowded world?

You Might Also Like