The 27 Most Iconic Physiques in Hollywood History and How They Got So Ripped

In need of some fitness inspiration? Well, you're in luck: We reviewed the greatest bodies ever to grace the silver screen and picked 30 cinematic icons who have defined the male physical ideal. Have a look–and then act on their methods.

Chris Evans, Captain America: The First Avenger (2011)

Few superhero film body transformations are as striking as that of Steve Rogers, who goes from big-hearted wimp to broad-chested warrior after an injection of super-soldier serum. Unfortunately for Chris Evans, the actor who portrayed him, the process was much more painful in reality than a quick jab. He was drilled two hours a day for three months by Simon Waterson, who also trained Daniel Craig for Casino Royale, targeting two major muscle groups at a time before moving onto the core. At least he didn’t have to do any cardio.

Jason Momoa, Conan the Barbarian (2011)

This reboot was ambitious in several respects: the original had achieved Thulsa Doom-level cult status, while Arnie, who played Conan in the 1982 version, had won his seventh Mr Olympia competition not long before filming. But while the reboot failed to launch a franchise, it made Momoa one of his generation’s definitive man mountains, be it as Khal Drogo in Game of Thrones or as Aquaman in Justice League.

For the role, Momoa built muscle and savaged fat with trainer Eric Laciste’s high-volume half-hour sessions. He would perform seven reps of squats, shoulder presses, incline benches, cable crosses or pull-ups, rest for a few seconds, then repeat for a total of seven sets. Then he would do six sets, then five – and the same all over again with two more exercises. Barbaric.

Harrison Ford, Original Indiana Jones (1981-89)

Temple of Doom gave us one of cinema’s most enduring body images: Indy on the rope bridge, his sleeve ripped to expose his sinewy arm. Jones was supposed to be younger than he was in Raiders of the Lost Ark, so Ford hired trainer Jake Steinfeld. Before filming, he hit the weights; on shoot days, he rose at 5am for pull-ups, dips, press-ups and sit-ups. The scene in Raiders where Karen Allen’s Marion tends to his wounds surely inspired a legion of impressionable boys to whip themselves into shape.

Ryan Reynolds, Deadpool (2016)

Hitherto best known as college “party liaison” Van Wilder, Ryan Reynolds’ cubed abs in the 2004 vampire movie Blade: Trinity put him on the lifting fraternity’s radar – but

it wasn’t until his title role in Deadpool that he graduated from romcom cheesecake to wisecracking beefcake. And while the film doesn’t so much poke fun at the inescapable comic book adaptations as fillet them with twin katanas, Reynolds’s physique was

no joke – nor was it obscured by CGI, as in his 2011 career low, Green Lantern.

Trainer Don Saladino devised a program called “jump, throw, carry”, incorporating

a plyometric bound, med-ball slam and farmer’s walk; this was followed by one of the Big Four (a bench press, squat, deadlift or military press session) and isolation work. Deadpool’s beloved chimichangas were presumably off the menu.

Dolph Lundgren, Rocky IV (1985)

After winning a scholarship to study chemical engineering at MIT, the Swede was scouted to be a boxer in New York. He was talked out of going pro by, among others, his then girlfriend, Grace Jones, whom he had met while moonlighting as a security guard in Sydney. Instead, his agent sent him to audition for “some boxing movie." Unlike in Rocky IV’s iconic montage, Lundgren trained alongside Stallone six days a week for five months: an hour of weights (chest/back, shoulders/arms or legs) in the morning, then two hours of boxing in the afternoon. Even if you didn’t know he was a former European Kyokushin karate champion, you only had to look at Lundgren to know he’d win in a real fight, too.

Jake Gyllenhaal, Southpaw (2015)

hose first shots of Jake Gyllenhaal as Billy Hope – snarling, snaked with veins – hit the internet like a hook to the jaw. Having lost 14kg for Nightcrawler, he had five months to resemble a boxer not only in physique but also in technique. He achieved this by training twice a day – take a look at the training montage, soundtracked by Eminem. Gyllenhaal also flipped a 160kg tyre and beat it with a 10kg sledgehammer, ran eight miles and performed 2,000 sit-ups a day, and skipped “shitloads”.

Mark Wahlberg and Dwayne 'The Rock' Johnson, Pain & Gain (2013)

These two Men’s Health cover institutions could have made it onto this list for most of the films in their chest-and-back catalogue. But they have rarely been bigger or better than in this strange but true story of meathead bodybuilders who hatch–then bungle–a kidnap plot. The film is also a smart satire of the particularly American obsession with, er, bigger and better. Johnson followed a five-day body-part split, though his trainer Dave Rienzi asked him to reduce his workouts to one intense hour or less, as any more can be counterproductive.

Supervised by former American football trainer Brian Nguyen, Wahlberg’s bulk-up was more sports scientific, with posterior chain activation, kettlebell swings and goblet squats alongside the bench press.

Henry Cavill, Man of Steel (2013)

Though Henry Cavill refined his physique for Batman v Superman (2016) and Justice League (2017), nothing in either movie etched itself in the memory like those first shots of a shirtless, stacked Clark Kent. Cavill worked with Mark Twight and Michael Blevins of the uncompromising Gym Jones in Salt Lake City, which also chiseled the cast of 300

into Greek statues. He trained for two months alone before joining them for a grueling four months in Los Angeles. Sadistic workouts such as 100 front squats with the equivalent of his bodyweight in iron were conceived to bolster mental fortitude as much as physical appearance – Cavill’s steely determination is as visible as his muscles.

Michael B. Jordan, Black Panther (2018)

It’s a mark of the intimidating shape he’s in that when Jordan’s usurper Erik “Killmonger” Stevens disrobes to reveal his scarred torso ahead of combat with Chadwick Boseman’s King T’Challa – AKA Black Panther – you fear that nine lives might not be enough. Jordan was impressively fit in 2015’s Creed but, with trainer Corey Calliet, he went into beast mode for Black Panther, upping the weights until he was benching 50kg dumbbells. As Stevens, he is the muscular embodiment of 21st-century black power.

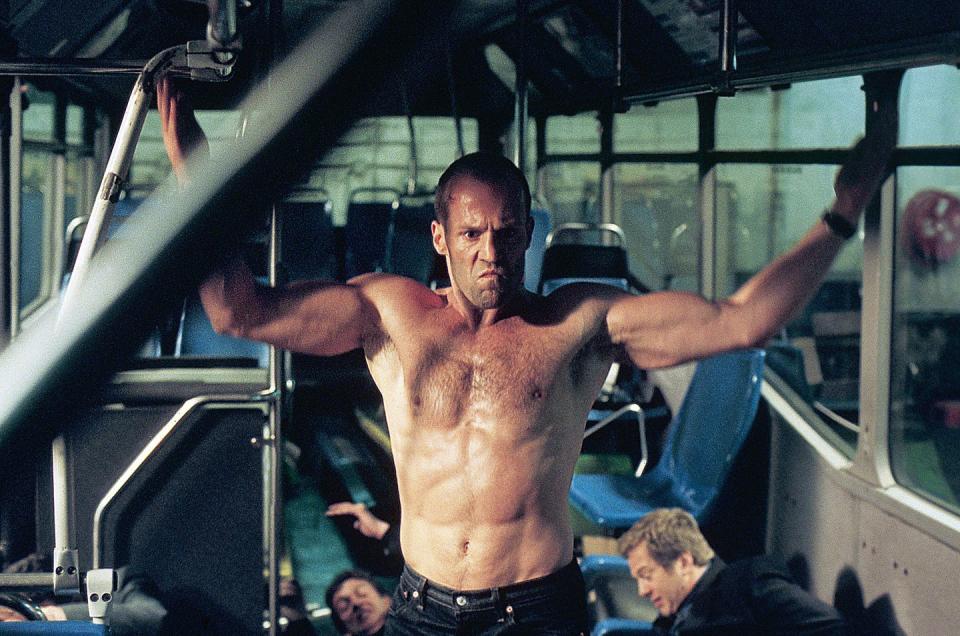

Jason Statham, The Transporter (2002)

If Lock, Stock (1998) and Snatch (2000) showcased the patter that Jason Statham picked up as a street trader, The Transporter was the perfect vehicle for the gravity-defying athleticism he developed as a diver for the British national team. As he demonstrates when he uses his top to tie up goons before kicking his way across an oil-slicked garage floor, it’s not just about the polished chassis but what’s under the hood. Through sequels, similar franchises (The Mechanic) and an ever-evolving program of martial arts, gymnastic skills and Olympic lifts, he continues to turn back his mileage clock.

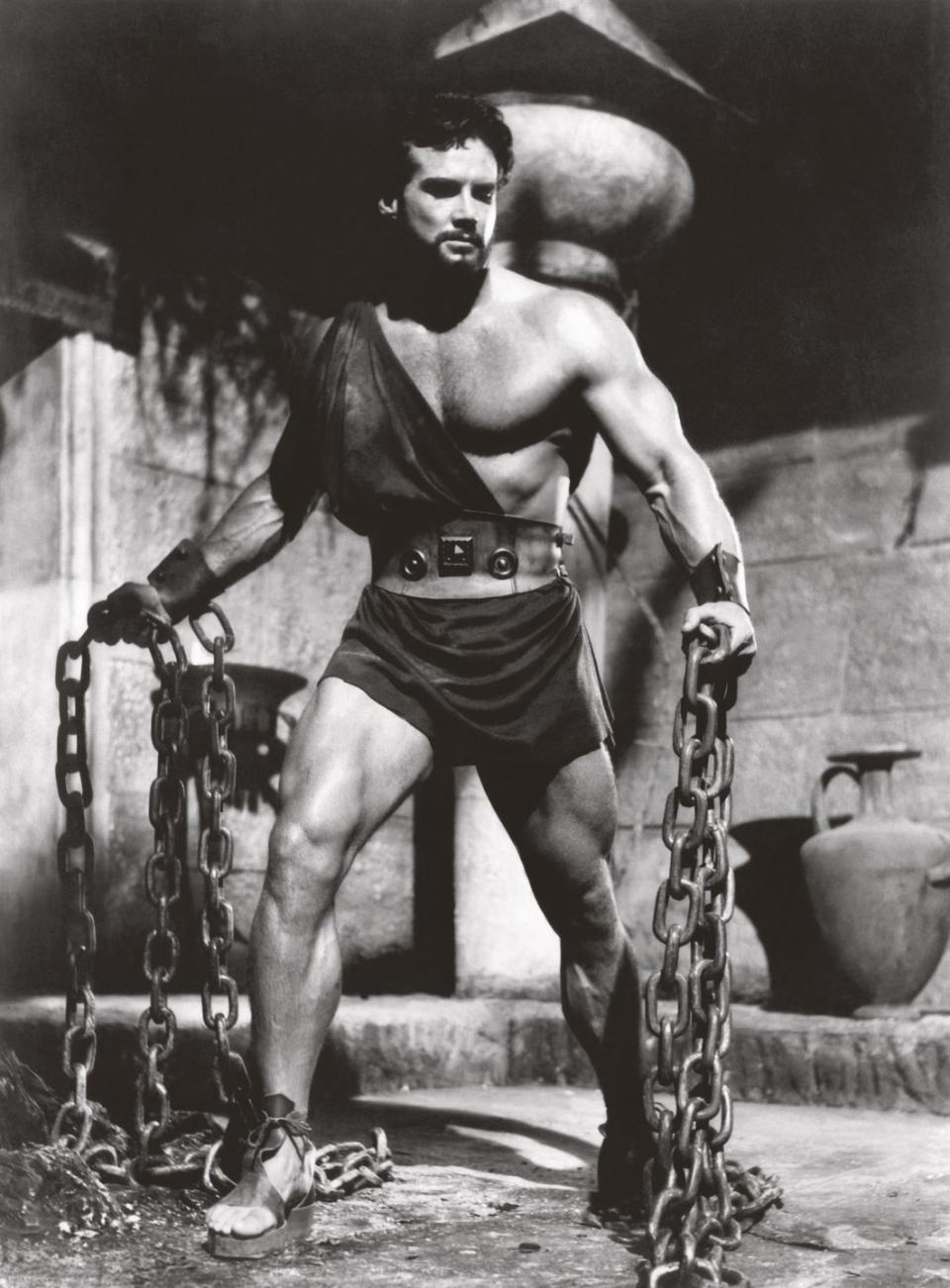

Steve Reeves, Hercules (1958)

The first bodybuilder to become a household name, Reeves was an inspiration to

Arnold Schwarzenegger and Sylvester Stallone, who watched Hercules “15 or 16 times” as a 12-year-old. The 1950 Mr Universe experimented with then novel methods such as supersetting and performing leg exercises last, so fatigue wouldn’t inhibit his upper-body work. He criticized modern bodybuilders’ steroid use: “If a man doesn’t have enough male hormones in his system to create a nice, hard, muscular body, he should take up ping-pong.”

Chris Hemsworth, Thor Ragnarok (2017) and Avengers: Infinity War (2018)

A god among supermen, Chris Hemsworth’s Thor is so heavenly-bodied that he makes Chris Pratt’s Star-Lord feel unworthy. Hemsworth – a rare actor who is as big off screen as he looks on it – and trainer Luke Zocchi mixed bodybuilding with functional exercises such as battle ropes and bear crawls to mould a more defined physique than in previous Thor films. The thunder deity’s triceps are like horseshoes smithed in the forges of Nidavellir, which Thor reignites by bicep-curling open the doors while being blasted by the core of a dying star. This may not make any sense unless you’ve seen Infinity War, but suffice to say that it’s the ultimate expression of “sun’s out, guns out”.

Tom Hardy, Warrior (2011)

For someone neither big (he is under 5ft 10in) nor hard (by his own admission), Tom Hardy does a convincing impression of big, hard men: notably the unhinged career convict in the 2008 drama Bronson and the unintelligible supervillain Bane in 2012’s The Dark Knight Rises.

Charging through hapless opponents like a young Tyson, his MMA fighter Tommy Conlon is in a lower weight category but meaner and leaner, Hardy having shed 15% of his body fat while adding 20kg of muscle. His trainer Patrick “Pnut” Monroe, a 15-stone former US marine, employed a technique called “signaling”: spreading exercise in bursts throughout the day in order to encourage the body to adapt. Although if you’re doing two hours each of boxing, kickboxing, choreography and lifting, as Hardy was, that’s hardly necessary.

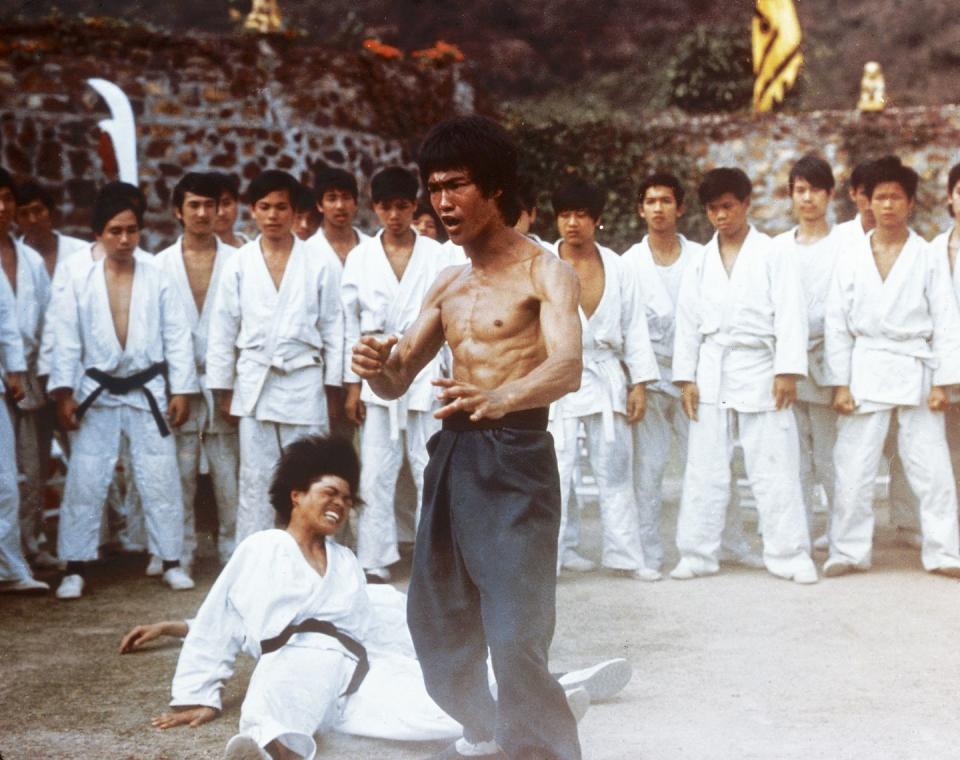

Bruce Lee, Enter The Dragon (1973)

Posthumously released, Bruce Lee’s final completed film made a greater impact than his legendary one-inch punch. Still the highest-grossing straight martial arts movie of all time after adjusting for inflation, Enter the Dragon snap-kicked open the doors of Hollywood studios that had hitherto portrayed Asian men as more Charlie Chan than Jackie (whose neck Lee snaps in villain Han’s underground lair).

You can draw a direct line from the proliferation of dojos across the US that followed the film to the popularity of MMA today. “Father of bodybuilding” Joe Weider called Lee’s physique the most defined he had ever seen. Years before Pumping Iron, the aspirationally six-packed star lifted functionally, ran meditatively and skipped religiously. He also invented an abs exercise: the “dragon flag”.

Hugh Jackman, The Wolverine (2013)

Known as “Huge Jacked Man” in the MH offices, the actor and member of the 1,000lb deadlift club raised his own bar with The Wolverine, in which he was more ripped than a pair of Logan’s gloves. The X factor was brought by trainer David Kingsbury, who took him out of his 8-12-rep comfort zone. Jackman started his sessions with heavy compound lifts, laying down a strong foundation and increasing his capacity for bodybuilding-style sets later on. Keeping his body fat down while bulking up, he hit his personal best – at the age of 44.

Christian Bale, American Psycho (2000)

Bale has become synonymous with physical transformations, dropping more than 25kg for The Machinist, then bulking up so much for Batman Begins that he was asked to lose 10kg. But Christian Bale’s best work is in American Psycho, ironically interpreted as an etiquette manual by many bankers. The actor was so determined to land the role that he reportedly trained three hours a day, six days a week, for the nine months it took Leonardo DiCaprio, whom the studio wanted, to depart the project. The precise nature of his workouts is unknown, but the smart guess is that he went method: crunches with an ice pack on his face and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre on TV.

Marlon Brando, A Street Car Named Desire (1951)

Taking on the role of cruel but charismatic Stanley Kowalski today must be a thankless task, as Brando will forever own it. When he first played the part on Broadway, before starring in the film version, women threw their hotel room keys at him. Gore Vidal wrote that the “earthquake” of Brando’s Kowalski in his torn, sweaty T-shirt caused a seismic shift in American sexuality: “Before him, no male was considered erotic… A man was essentially a suit, he wasn’t a body.”

Brando used his to entice and intimidate – but his performance owed a lot to the gym. It was based on boxer Rocky Graziano, whom he had sneakily observed there. By way of gratitude, the actor gave his unsuspecting muse two tickets to the show.

Daniel Craig, Casino Royale (2006)

When Craig’s 007 emerged from the water with his gym-buffed pecs in Casino Royale, he heralded a sea change in masculine ideals. The now iconic scene evoked Ursula Andress’s entrance in Dr No, but with Bond and not his “girl” as our focus. Craig claimed the moment was accidental: shallow water had forced him to stand. His blue trunks later sold for £44,450 at a charity auction.

The actor wanted his Bond to look lethal. Trainer Simon Waterson gave him a license

to kill with a combination of powerlifting and compound exercises that elevated his heart rate to build muscle while maintaining leanness.

Brad Pitt, Fight Club (1999)

“Self-improvement,” declares Brad Pitt’s Tyler Durden, “is masturbation.” Despite the unambiguous message of the psychopathic Durden – the alter-ego of Edward Norton’s unnamed narrator – the black-eyed comedy popularized the term “six-pack”, as well as “inguinal crease”. (The result of awe-struck viewers searching: “What is that diagonal line that runs from Brad Pitt’s hip to his crotch?”)

Click-bait articles purport to contain Pitt’s “actual Fight Club workout”, but he has yet to share his method (he was seen on set using hand weights). Charlie Hunnam’s quip that Pitt “ruined it for everyone” doesn’t just apply to his fellow actors.

The Cast of 300 (2006)

This swords-and-six-packs epic has entered the fitspiration pantheon, and the way that

the Spartan warriors were battle-hardened has been mythologized. Mark Twight and his Gym Jones team subjected cast, crew and even director Zack Snyder to constantly shifting functional fitness tests and calorie restrictions. Four months of Hades culminated in a 300-rep examination: 25 pull-ups, 50 deadlifts with 135lb, 50 press-ups, 50 box jumps, 50 floor-wipers with 135lb, 50 kettlebell cleans and presses with 35lb, and another 25 pull-ups. Star Gerard Butler described Twight’s modus operandi as “difficult in the kind of way where you wish you had never been born – and even more than that, wished he had never been born”.

Sylvester Stallone, Rambo III (1998)

Sylvester Stallone was absurdly chiseled in Rocky III. Preparing for the role, he spent all day running, sparring, lifting, skipping and swimming, cutting his body fat to 2.8% at a lean 73kg. The International Federation of Bodybuilders named him the “Body of the Eighties”. For the third Rambo, however, Stallone pumped himself up into a man-sized action figure who could almost single-handedly take on the Soviet army, by performing pull-downs with 125kg at 82kg bodyweight.

The movie had such impact that the US policy of violent, unilateral interventions in countries such as Nicaragua was dubbed “the Rambo Doctrine”, and there was concern that the film might even undermine improving relations with Russia.

Arnold Schwarzenegger, Pumping Iron (1977)

Naturally, Arnold Schwarzenegger is numero uno – but for a documentary? Not quite, since much of Pumping Iron was, shall we say, exaggerated. The sixth consecutive Mr Olympia victory, the training methods still traded on by muscle mags four decades later – all of that is true. “But there were certain things that are not true,” Arnie admitted in an interview marking 25 years since the film’s release. “That’s why we never called it a documentary. We called it a ‘docudrama’... because certain things were created in order to make it more interesting.”

In reality, Arnie had already hung up his posing pouch before the 1975 contest to pursue acting. He was persuaded to come out of his brief retirement by George Butler, who with Charles Gaines had written a Pumping Iron book that featured Arnie and wanted to turn it into a film. To create drama, Schwarzenegger invented the character of a relentless terminator: “I said to myself, ‘How can I sell the idea that I’m a machine that has no emotions?’” His story about missing his father’s funeral because it clashed with his contest prep was borrowed from another bodybuilder; his claim that the pump was like “coming” was deliberately sensational to generate press. (“It’s not, trust me,” he said.)

At the time, bodybuilding was “the least glamorous sport in the world”, according to co-director Butler: a niche subculture confined to the kind of dark Brooklyn dungeon where challenger Lou Ferrigno (who became TV’s Incredible Hulk) grunts and grimaces. The contrast with glowing Arnie sculpting himself in California’s Gold’s Gym and sunning himself on nearby Venice Beach was purposely made stark by the film-makers. As Butler said, “We defined bodybuilding to a world that knew nothing about bodybuilding.” Their movie brought it into the light.

With magnetism so strong that he almost didn’t need to lift the weights, Arnie’s Pumping Iron persona gave bodybuilding mass appeal. Hundreds of gyms sprang up across the US. Butler estimated that just 25,000 Americans lifted weights before the film’s release; a 1982 poll put the number at 34 million. Having previously struggled to find acting roles because of his size and accent (his voice was dubbed over in 1970’s Hercules in New York), Schwarzenegger broke Hollywood’s leading man mould and recast it in his own image. As many of the entries on this list demonstrate, that mould is still in use. Bodybuilding is mainstream.

Though he has always been a campaigner for an active lifestyle, Arnie has not been an entirely benign influence. Natural Born Heroes author Christopher McDougall believes his fame contributed to an epidemic of muscle dysmorphia and static, aesthetic-fixated exercise that we’re still recovering from. Then there’s Schwarzenegger’s – at the time legal – steroid use, which gave a false impression of what was attainable. But, as we’ve come to realise, (clean) resistance training confers health benefits on men of all shapes and sizes. Without Arnie in Pumping Iron, would any of us even lift?

Jean Claude Van Damme, Bloodsport (1988)

Unlike some of his action hero peers, the functional Muscles from Brussels – a karate black belt and ballet student, as well as Mr Belgium – could move with a fluid grace, which is why he was initially cast as the agile alien opposite Arnie in Predator. Bloodsport, a fight film about an illegal martial arts tournament, made JCVD a star. It also inspired both the sport of MMA and the Mortal Kombat video games: the character Johnny Cage is based on him, right down to his splits. Van Damme was into flexibility before it was cool – or he parodied it in those Volvo ads.

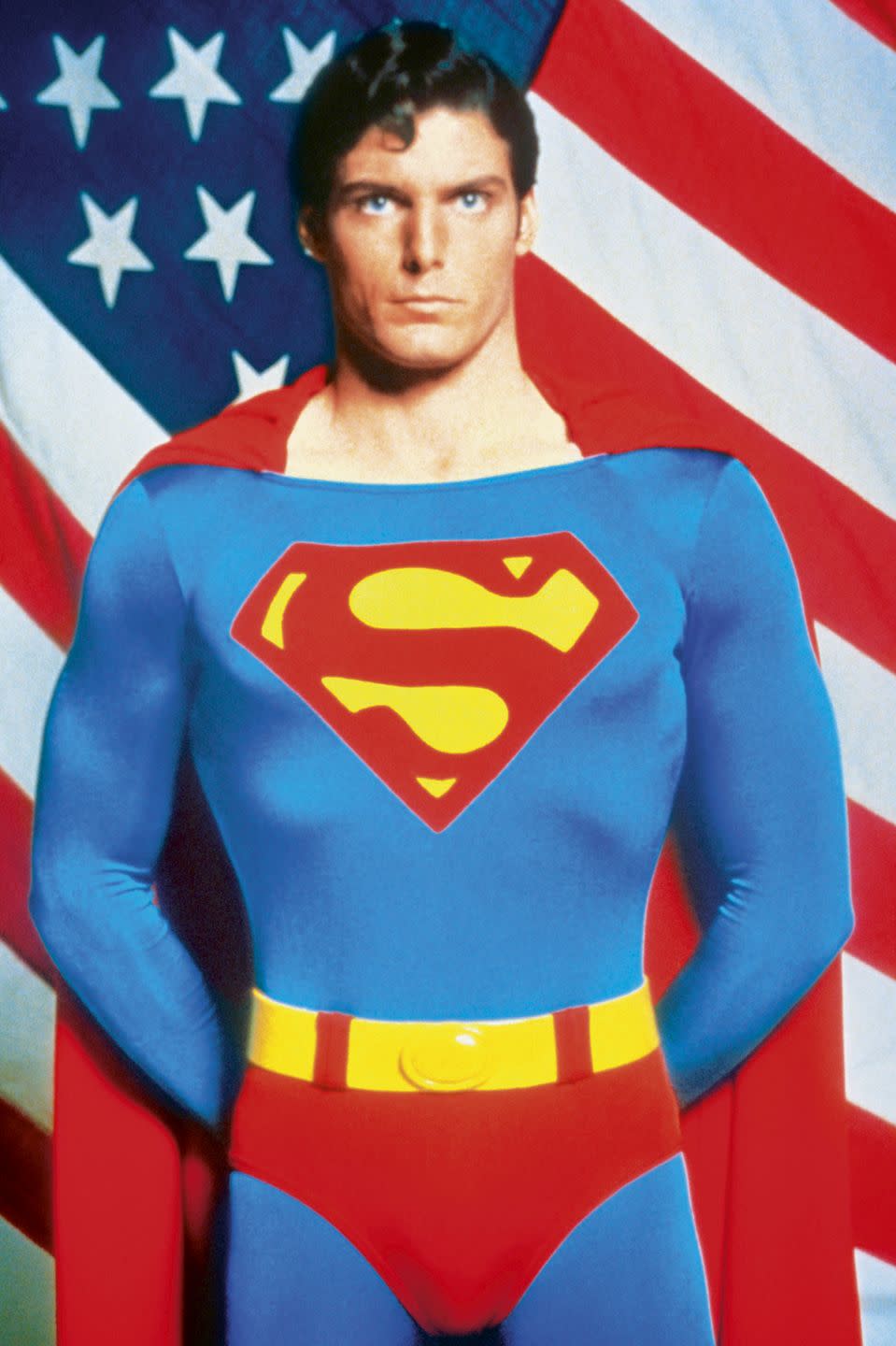

Christopher Reeve, Superman (1978)

At 6ft 4in and 80kg, Reeve was initially dismissed as “too skinny” to play the Man of Steel. A padded suit was offered, but Reeve wanted to supply his own muscle. So, bodybuilder and actor David Prowse (who played Darth Vader) was brought in to work Reeve into shape. After six weeks of training and eating four meals a day, he had bulked up to almost 100kg. In unflattering Lycra that even Henry Cavill was at first apprehensive about donning, Reeve made you believe that a man could fly.

Sean Connery, Dr No (1962)

He may not have shaken or stirred many supplements by today’s standards, but Connery was a bodybuilder in his early years who took part in 1950s Mr Universe competitions. Reluctant to stop playing football, however, he retained an athletic physique that left him unable to measure up to the (possibly artificially) supersized Americans. So he tried his hand at another profession: acting.

A notorious snob, the 007 creator Ian Fleming initially disparaged the Scot as an “overgrown stuntman”. But film producer Cubby Broccoli’s wife, Dana, saw something that the author didn’t: “He moves like a panther,” she said. Indeed, his mobility was ahead of its time, as this picture proves. More than any other film character, James Bond has become a template for men – and Connery set the mould.

Ryan Gosling, Drive (2011)

Ryan Gosling doesn’t expose his “photoshopped” abs in this film – as he does in Crazy, Stupid, Love – but like the threat of violence, the presence of his physique is ever felt. When he carries his neighbor Carey Mulligan’s son to the synths of College’s “A Real Hero”, his back muscles visible through the cotton, something primitive stirs in men and women alike. His character is a strong, silent archetype, ready to do whatever it takes to protect those he loves, even if it ultimately drives them away. It’s no wonder Gosling was hailed as “the new Brando”.

Will Smith, Ali (2011)

Will Smith had already gone from The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air to popcorn-movie king, but this Muhammad Ali biopic established him as a heavyweight in both senses. For the ordinarily gangly actor, bulking up from 84kg to 100kg was “50 times harder”

than losing weight for 2007’s I Am Legend. Under the tutelage of Darrell Foster, who coached Sugar Ray Leonard, Smith trained six hours a day, five days a week, boxing, running and lifting. Within a year, he more than doubled his bench press from 80kg to 170kg. In a front double biceps pose, Smith says, “Ain’t this just the perfect specimen of a man?”

You Might Also Like