The 2020 New Deal Means Building Internet Access for All Americans

One of the more troubling realities that the coronavirus crisis has laid bare is just how far the United States has fallen behind in the digital economy. The systemic lack of digital infrastructure and digital skills throughout the country has meant that the sick struggle to use telemedicine, the elderly struggle to get groceries delivered, and the employed struggle to perform their jobs remotely. Some rural and low-income school districts have simply closed rather than offer virtual instruction to the privileged few who can access the internet from their homes.

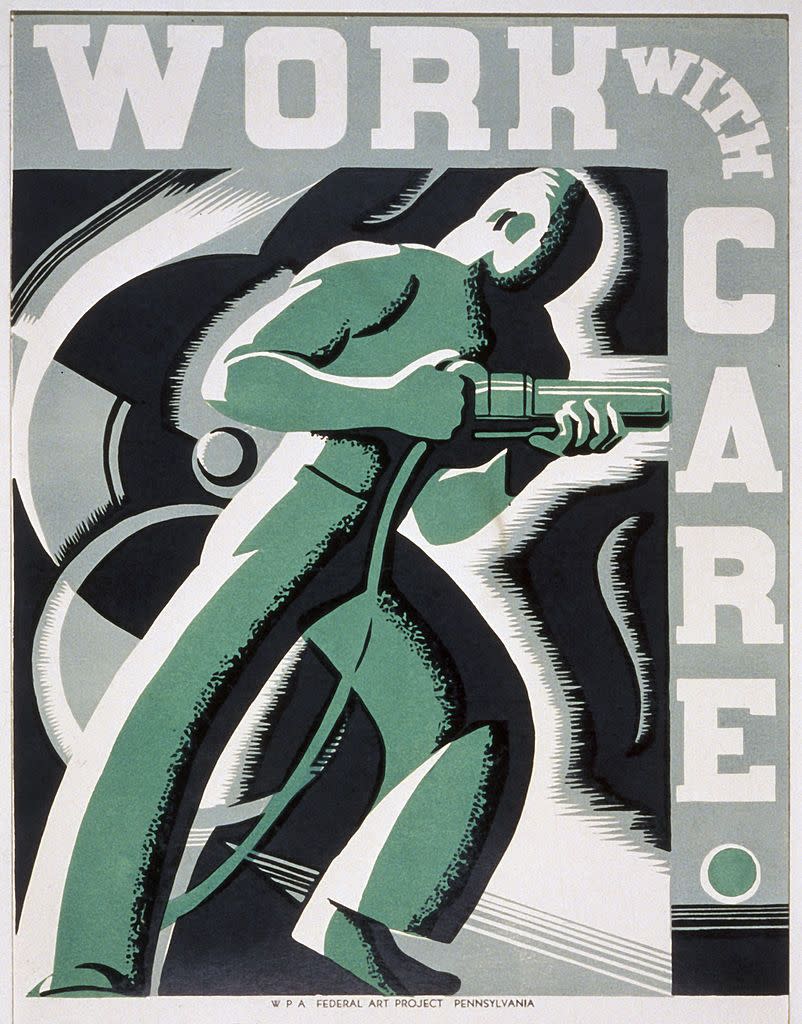

The last time that the country faced an economic crisis of this magnitude was the Great Depression. In 1935, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, fed up, decided that it was time for the government to intervene more directly in the market. To do so, he created the Works Progress Administration. The WPA’s aim was two-fold: to create work for the unemployed and to build the infrastructure that would power the economic fortunes of the country for coming decades. FDR’s ambition was grand: “The recovery we seek, the recovery we are winning, is more than economic,” he said. “In it are included justice and love and humility, not for ourselves as individuals alone, but for our nation.” In its nearly decade of existence, the WPA fulfilled these goals admirably, employing around 8.5 million people and building the highways, bridges, dams, and airports that underpinned the country’s economy for many years to come.

We need a similarly ambitious plan today, but one tailored to our own needs and times.

Today’s data economy is driven not by trains, planes and automobiles but by internet connections, digital skills, and technological prowess. We don’t need a Works Progress Administration. We need a Digital Progress Administration.

What might a Digital Progress Administration look like? Like the WPA, its goals would need to be two-fold: to put American workers back to work and to create the digital infrastructure that will power our economy in future years. It would focus on the high-priority projects that the country needs to compete in the virtual world.

A first priority for a DPA would be to develop the world’s fastest, most reliable and most widely available internet network. Telecommunications companies like AT&T, Verizon, and T-Mobile are already working on projects to create advanced so-called “5G” networks, but their efforts to date have been slow and limited. High frequency 5G networks, while incredibly fast, also require denser base station points than traditional cell phone networks and are, thus, labor intensive. A DPA could help administer and fund the roll-out of 5G networks across the country in a faster and more efficient manner—and ensure that all citizens, rich and poor, urban and rural, would have access to them.

Second, a DPA could focus on bringing the all-important computer chip industry back to the United States. In recent years, U.S. firms have lost ground to foreign firms, with Taiwanese and Chinese firms fabricating many of the chips that power today’s ubiquitous smartphones and computers. A DPA could help subsidize fabrication plants for semiconductor companies to employ more workers. The numbers would be large—Intel employs 20,000 workers at its Hillsboro, Oregon plant alone —and provide tremendously valuable skills to workers.

The DPA would create jobs in the growing industry of digitization and automation. More and more corporations are deploying machine learning and Big Data techniques in their businesses, and many of these projects require substantial numbers of people to operate properly. Mapping companies use humans to identify street lines and buildings in images. Medical companies use humans to analyze MRI scans. Facebook uses humans to moderate content. The applications are nearly limitless, and a DPA could help ensure that the industry receives the investment it needs.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, a DPA need not establish its priorities in isolation and on its own. Technology companies have knowledge about competitive pressures and market dynamics that government bodies could never attain, and thus a DPA could encourage companies to propose their own digital initiatives. These proposals would be analyzed under the same basic principles animating the body as a whole: first, projects should employ substantial numbers of workers; and second, projects should provide substantial long-term benefits for the country’s digital economy.

Not all of these efforts could start right away. A DPA might need to pay for workers to receive training before they have the digital skills needed to perform some jobs—while adhering to CDC recommendations on social distancing. Any program of the scope proposed here would be expensive and might raise concerns about data privacy and increasing government surveillance.

But if anything, these limitations—privacy concerns and high cost—show just how integral a Digital Progress Administration would be to the country’s prosperity. Many of the tasks—such as automation and digitization—could be performed safely at home. Others—such as internet infrastructure—would help enable the other tasks to be performed in the first place. Bringing chip fabrication and 5G equipment back to the United States could in fact improve data privacy and reduce national security concerns, given the increasing worries that these supply chains are vulnerable to Chinese cyberespionage. And, finally, training and education could go a long way towards ensuring that workers have the skills needed to thrive in the new digital economy.

We have spent billions of dollars helping people absorb the devastating blow of losing their livelihoods. Why not invest in putting them to work building the digital economy that this country desperately needs?

William Magnuson is an associate professor at Texas A&M Law School and the author of Blockchain Democracy: Technology, Law and the Rule of the Crowd.

You Might Also Like