12 Influential Women Designers in Fashion History

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Long before the origins of what would become Women’s History Month were put in motion in 1981, female designers and pioneers in fashion were carving out their own paths to empower women with clothes that instill confidence and to create jobs that sustain livelihoods.

While millions associate fashion purely with style, these troubadours used their designs to create a more individualistic route to self expression and to alter preconceptions of what a woman should be. Conformity was not what they were after. Interestingly though, these leaders often created garments with comfort in mind so as to allow the wearer present their truest sense.

More from WWD

How Changing Views About Marriage and Weddings Are Impacting the Bridal Industry

Dunkin' Donuts Serves up Apparel, April Fool's Day Name and Supposedly 5,000 Coffee Choices

WWD has delved into its archives to highlight how these female creatives still influence fashion today.

Madame Grès

It is not often that fashion acquires genius but, once in a while, it shows up.

Unadorned in her trademark beige turban and straightforward manner of dress, Madame Grès became elusive except to the commitment she held to the art form she adored — the couture.

Born Germaine Emilie Krebs, she took her first alias, Alix Barton, as a milliner. In 1936 she made her mark on couture under the name Alix, and by 1942, she dropped Barton and assumed the surname Grès from her only marriage in 1942.

Madame Grès, or simply Grès as she would be known, experimented with fabric and form to achieve perfection. A trained sculptor, her approach informed mathematical agility to designing with fabric. She was not known to use a pattern to create, nor toiles (muslins), and she minimized needle and thread use because, as she often stated, she had no other choice.

“From the beginning…I didn’t have the knowledge. I took the material and worked directly on it. I used the knowledge I had, which was sculpture,” the couturier told WWD in 1963.

Her famous Grecian-influenced column gowns of the 1930s, made of silk, rayon and later, polyester jersey, are the anthesis of her oeuvre. The dresses, sculpted and sewn on the body, selvedge to selvedge, no two alike using an average of 13 to 23 meters of uncut fabric, remained weightless. Grès’ continued to be influenced by multicultural costumes throughout her career.

With her house thriving in the 1950s and 1960s, she introduced her perfume Cabochard (which translates to “pigheaded”). Ironically, the successful scent’s name was deemed appropriate to Grès, considering her attitude to designing anything other than couture — she created her first ready-to-wear collection in 1981 — which ultimately restricted the house’s growth.

Grès’ approach to her art informed the singularity of her genius. But her death, like her life was shrouded in mystery. While it was reported to the fashion press falsely in 1994, her actual passing a year earlier was kept secret by her daughter. Appreciation for Grès’ work has allowed her most essential pieces to be preserved by time, allowing her commitment to the couture she loved and her legacy to stay alive.

Coco Chanel

Prior to her death in Paris at the age of 87 in 1971, Gabrielle Bonheur “Coco” Chanel had been working up until the last minute on her couture collection. Considered by many to have been the greatest fashion force who ever lived, she created a fashion spirit, as well as a look. Aside from influencing most of the best young designers of her time in Europe and the U.S., she has had a lingering impact on fashion today.

For 60 years, Chanel epitomized her signature style simply by wearing her creations. Liberating women from corsetry and other restrictive clothing, she borrowed somewhat from men’s wear looks and created a sporty casual chic post World War I. The Chanel suit, the little black dress, costume jewelry, trenchcoats, the quilted leather purse, turtlenecks, pants, peacoats and Chanel No.5 fragrance remain standbys today.

Chanel was once described by Pablo Picasso as having “more sense than any woman in Europe.” Her career began around 1912 (though she said it was 1914) with the opening of a small hat shop in Deauville. With her fiancé at war, she was looking for something to pass the time. After borrowing a sweater from a jockey at the races one day to fend off the chill, Chanel sparked a sweater trend with all “the smart Deauville ladies” within a week. Provocative and controversial, Chanel was criticized by many for her romantic ties to a German diplomat during WWII and the years that followed. The designer returned to Paris in 1954 and reopened her couture house. In the years that followed, Chanel, who had been born into poverty, built up the business and a following.

The allure of Chanel was chronicled in 1956, when WWD reported a sighting of her slipping unnoticed from her Ritz Hotel apartment to her couture house across the street. “She likes cigarettes, movies, solitude, sees few friends and as often as possible goes to Switzerland to get away from business,” the article noted. When the Duke of Westminster proposed marriage, Chanel famously turned him down, saying, “There are lot of duchesses, but only one Coco Chanel.”

As an arbiter of taste, Chanel inevitably dealt with her share of knockoffs and copies. She once spoke of Yves Saint Laurent’s “excellent taste. The more he copies me, the better taste he displays,” she said.

Several thousand people reportedly gathered outside of La Madeleine church during her funeral in 1971.

Bonnie Cashin

“Modern clothing is only valid if it works…and going into history for gimmicky ideas is not modern,” Bonnie Cashin told WWD in 1968.

Cashin distinguished herself by focusing on lifestyle dressing as opposed to market categories, as in dresses, suits and other sectors, as was the norm on Seventh Avenue. Born in Oakland, Calif., and raised in San Francisco and Los Angeles, Cashin excelled with pragmatism. Her design sensibility was hatched in childhood. Her mother ran a custom dress shop and Cashin started sketching as a toddler.

Before her high school graduation at the age of 16, Cashin designed costumes for a local dance troupe at Fanchon and Marco. Grasping the importance of functionality in design was one of Cashin’s strong suits. After relocating to Manhattan to study dance and take courses at the Art Students’ League, she went on to design costumes for the Roxy Theater in the ’30s. After seeing Cashin’s design on stage, Carmel Snow, editor in chief of the American edition of Harper’s Bazaar from 1934 to 1958, recommended her to Adler & Adler, which she joined full-time in 1938.

Not a fan of the Seventh Avenue mind-set of categories, Cashin later hit Hollywood as a costume designer at Twentieth Century Fox. After designing costumes for 60 films, she returned to New York, launched a collection with Adler & Adler, winning a Coty award and a Neiman Marcus award that year. In 1951, she started her own design studio. In the 30-plus years that followed, Cashin created ponchos, leather piped tweed suits, geometric-printed cashmere sweaters and more. Oversized interior pockets, sewn-in bags and equine clasps were a few of her signatures. In 1964, Coach tapped Cashin to design women’s accessories — something she had first incorporated into her designs in the ’30s. The American sportswear pioneer continued to run her design studio until the mid-’80s.

Cashin, who died in 2000, having largely kept her distance from the grips of fashion’s conventions, has largely not been credited for her manifold forward-thinking contributions to the industry, which continue to impact fashion today.

“I didn’t want to be boxed in by any one company or any one design problem,” she once said. “I wanted to design everything that a woman put on her body. I felt that designing for the entire body was like an artist such composition.”

Claire McCardell

Millions of people around the world can be found at any given moment wearing ballet flats, sportswear with oversize pockets, strapless swimwear, zippered dresses, mix-and-match separates, feminine denim and versions of the monastic dress. Knowingly or not, they have the late fashion designer Claire McCardell to thank. Such wardrobe staples have been sported by generations of people, and are the rare fashion styles that stand the test of time.

Perhaps more than any other American designer, McCardell freed women from the constraints of appropriate attire. Emblematic of her exemplary “American look,” her creations can be found in the Smithsonian Institution and the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute. McCardell first won the prestigious Coty award, a precursor to the Council of Fashion Designers of America’s much coveted awards, in 1943 and then again in 1956. That ascent was notable for a designer, who had started her career by painting rosebuds on lampshades.

McCardell is credited with championing American sportswear, but she never shouted out her contributions. Upon her death of colon cancer at the age of 52 in 1958, WWD reiterated how she never had made any “I-was-first-with-it claims about fashion,” and had contended that too many elements enter into it, which “made the originations highly debatable.”

But consider her signature look. Created in 1938, “the Monastic” dress, had large patch pockets, loose sleeves and a roomy fit from being cut straight from the shoulder to the hem and gathered at the waist with a belt or sash. Three years later she whipped up five pieces that could make nine outfits. The wraparound popover dress, which was created in 1942, was even more versatile, as it could be worn as a party dress, a housedress, a swimsuit cover-up or a robe. Her tie-together “diaper” bathing suit anticipated the daring beachwear styles of the 1980s. Spaghetti straps on evening gowns, the modern dirndl, peddle pushers, and the “popover dress” were a few of her other greatest hits. She also popularized leotards and tweed evening coats. In a 1955 magazine article written by Betty Friedan, McCardell said, “You have to design for the lives American women lead today.”

McCardell was only 16 when she enrolled in home economics at Hood College. She later transferred to the New York School of Fine and Applied Art and studied abroad for a year at Place des Vosges in Paris, where she got a closer look at the constructionism of Madeleine Vionnet. But McCardell forged her own path, and was disinterested in any European copies. Hired by Robert Turk as an assistant designer in 1930, when he drowned in 1932, she was asked to finish the Townley Frocks collection. During a trip to Paris for inspiration, she took to the streets and art galleries for inspiration to create clothing for working women of all classes.

After a stint at Hattie Carnegie, McCardell returned to Townley Frocks and debuted a signature label — one of the first American designers to do so — in 1940. Eighty-four years later, McCardell’s forward-thinking still influences major American fashion designers including Tory Burch, who wrote the foreword for the reissued version of McCardell’s book, “What Shall I Wear? The What, Where, When and How Much of Fashion.” Burch has said of McCardell, “Everything she did had such an impact on so many that it’s hard to even quantify what her lasting impact is because it’s been everywhere.”

More than 300 people turned up at McCardell’s funeral at St. James Church in 1958. McCardell’s estate was valued at just more than $20,000 after her death. Her label can no longer be found on any apparel, but she continues to inspire. Burch told WWD in 2022, “Here’s someone who transformed the way that women dressed. Beyond our industry, I don’t feel that she gets the credit that she deserves for really changing the way women dress, embracing women’s empowerment and having women feel freer to express themselves in the way that they dressed in the ’40s.”

Anne Klein

Anne Klein, born Hannah Golofski, is synonymous with American sportswear. The company she created in 1968, Anne Klein & Co. in 1968, grew out of a concept. Chic, comfortable, uncomplicated fashion that fits well and is wearable from season to season. “No fads,” the designer once declared to WWD.

Klein started working on Seventh Avenue at age 15 as a freelance sketcher. The young woman who daringly dropped out of school to pursue a fashion career formed her first successful company, Junior Sophisticates, with husband Ben Klein in 1948. By 1968, she was on her own. And by the mid-1970s, she changed the concept of American sportswear into what is known today as designer rtw.

So many pieces of clothing in today’s wardrobe could, in some way, be attributed to Anne Klein. She believed in easing women into new silhouettes by introducing them in her collections at the right time. Some of those staples include the button front A-line dress, the leather midi skirt, the long sweater vest cardigan, pants that fit perfectly. These and many more were a part of what WWD called Anne’s “separate into togetherness” concept. While women had long been buying sets, Klein introduced coordinated separates that would allow women to mix and match their wardrobe, a concept that was met with great success throughout department stores.

Klein never shadowed her contemporaries. She was the only woman from the American fashion industry invited to participate in the Battle of Versailles extravaganza. And with confidence, in 1968, she introduced the concept of group design when she opened Anne Klein Studios. The studio mentored and helped catapult the careers of many Seventh Avenue designers. Klein died from cancer in 1974, but her legacy lived on through designers like Donna Karan, who, similar to Klein, built women’s wardrobes while building her career.

Liz Claiborne

Some had felt Liz Claiborne was past her prime when she opened her namesake brand at the age of 47, but, she had a vision. Claiborne’s groundbreaking success was inevitably connected to how she wanted to live in her own clothing.

Anne “Liz” Claiborne was instantly recognizable with her oversized red glasses and short hair. Born in Brussels to American parents who came from a prominent Louisiana family, she began her career working as a design assistant and model. Her vision for easing the stress of dressing for working women came from her own experience. As a working mother, she knew that time was fleeting and that fussing over a wardrobe you couldn’t afford was pointless. So she, along with her husband Art Ortenberg, Leonard Boxer and Jerome Chazen, founded her namesake Liz Claiborne Inc. in 1976. While her partners focused on sales and operations, Claiborne focused on design.

By following her own sensibility for great design, color and bypassing the latest trends, Claiborne attracted a consumer, like herself, who also wanted to fill the void in their work wardrobes. She built a brand that leaned into comfort, with a focus on quality, stylish clothes at a value, and adding a commitment to interacting with the consumer drove the brand’s success. One of her first supporters was Saks Fifth Avenue.

This concept worked and Liz Claiborne went from one to more than 10 successful brands. By 1981 the company went public. By 1989 Claiborne and her partners turned the better-priced sportswear market into a multibillion-dollar industry. But the behemoth was larger than she could control creatively, and over time it lost the distinction it had become known for. Claiborne and her husband retired from Seventh Avenue to focus on philanthropic efforts and travel, leaving behind just under two decades of producing and acquiring a portfolio of 40 labels including Dana Buchman, Ellen Tracy, Juicy Couture and Kate Spade, among others. The award-winning designer, and first female CEO and chairwoman of a fortune 500 company, died from cancer in 2007 at the age of 78.

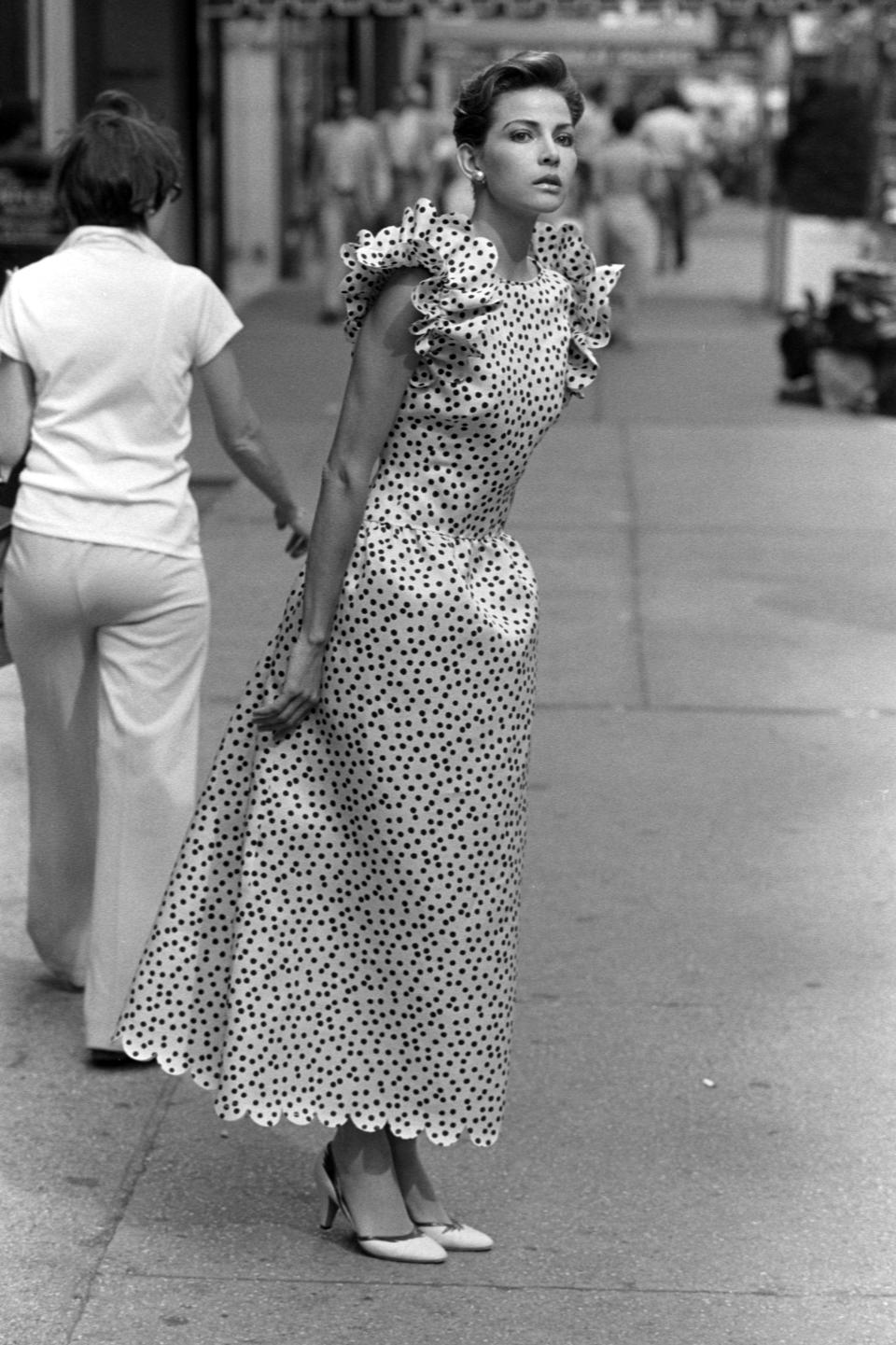

Carolina Herrera

Born in Caracas, Venezuela, Carolina Herrera launched her first signature collection in a show at the Metropolitan Club in 1981 with the encouragement of former Vogue editor in chief Diana Vreeland. Early on, one Saks Fifth Avenue executive said her designs “suit a certain customer, and the kind of thing she does is practically a lost art, at least in America.”

Media magnate Armando de Armas had offered to invest in Herrera’s business before the official debut and stayed on board until the company was sold to Puig in 2012. A pragmatist through and through, Herrera’s success has hinged on a diverse portfolio and a certain élan. As a mother of four daughters, her fashion insights are intergenerational. Evolving from early flamboyance to a more measured take on decorative chic, Herrera personifies the elegance her label offers to shoppers. “Fashion must be for today,” she told WWD several years ago.

In 2018, Herrera stepped away from her namesake company and was succeeded by Wes Gordon, who continues as the house’s creative director. The Barcelona-based Puig launched Herrera’s first fragrance in 1988 and bought the company outright in 2012. In addition to the signature collection, there is the CH brand with broad global distribution, including freestanding stores. Bridal and fragrance remain key components for the brand, which celebrates its 40th anniversary this year.

Donna Karan

Describing the upsides of her profession, Donna Karan once said, “The great thing about being a woman designer is you can be selfish.”

Born Donna Ivy Faske and raised in Queens, N.Y., the designer’s relatability and easy rapport with consumers have been constants throughout her career. After attending Parsons School of Design, Karan started her career at Anne Klein, where she worked her way up to codesigner with Louis Dell’Olio. In 1984, she ventured out on her own seeking to create a collection of modern clothes for modern people. With a jersey bodysuit serving as a core item, Karan created “seven easy pieces” that were meant to be interchangeable. Donna Karan International was created with her late husband Stephen Weiss and Takiyho Inc. “A woman needs it all, so I figured why not do it all?” Karan told WWD in 1986.

By the time she stepped down as chief designer of DKI in 2015, Karan had built a fashion empire from the ground up. DKI went public on the New York Stock Exchange in 1996. Along the way, Karan forged into contemporary sportswear in 1989 with the DKNY label. She later added jeans, underwear and kids’ clothing under that label, as well as a myriad of other products she designed. Karan also masterminded the Urban Zen lifestyle label.

The designer did face a firestorm of criticism in 2017 when she stated, when asked about Harvey Weinstein, then accused and since convicted of sex crimes, “How do we display ourselves, how do we present ourselves as women, what are we asking? Are we asking for it, you know, by presenting all the sensuality and all the sexuality?” Shortly after she apologized for her remarks in several interviews, one notably in WWD with then executive editor Bridget Foley.

Karan has been vocal about needing to shift delivery cycles to offer in-season shopping as a way to avoid markdowns and a glut of merchandise. She has also championed sustainability and supported artisans in Haiti and other locales.

Vera Wang

In her 31st year in business, Vera Wang is still challenging herself as a creator. “It’s my own personal learning procedure, and it’s my own growth, not only as a designer, but as a human being,” the designer once explained. “It gives me a reason to learn more, to study more.”

An accomplished competitive figure skater, Wang uses similar exactitude in her fashion designs. As an undergrad, she worked as a salesgirl at the Rive Gauche boutique on Madison Avenue as a summer job. A Sarah Lawrence grad, Wang first dove into fashion full-time at Vogue on the editorial side. Her 16-year run at Condé Nast included assisting Polly Mellen, former stylist and fashion editor with stints at Harper’s Bazaar and Vogue, with sittings. During one, famed photographer recommended that Wang be made an editor, and as a result, that happened. After three-year stint as an accessories designer at Ralph Lauren, she ventured out to start her own company.

Just shy of age 40 and in search of a wedding dress, Wang saw nothing she could relate to. Her friend Calvin Klein, once asked, “You’re going to design bridal dresses? Let me know when you get over that.”

But it’s something Wang never got over and she has folded in extra layers for that business through a deal with David’s Bridal. Her celebrity brides have included Kim Kardashian (for nuptials with Kris Humphries), Victoria Beckham and Chelsea Clinton. Recognized as she is for experimental workmanship and high-minded construction in her top-tier designs, Wang also designs for the masses, as evidenced by a long-standing deal with Kohl’s. The designer doesn’t take that lightly. “It means a great deal to me because I don’t know why women all over America shouldn’t get great clothes for their money,” she once told WWD.

Wang’s vast product range spans rtw, jewelry, home decor items, mattresses, cosmetics, fragrances, bridesmaid dresses, Wedgwood china, picture frames and more. All in all, the designer takes her work seriously, “I love clothing. I’m a collector and a curator. I have great respect for the craft,” she has said.

Diane von Furstenberg

Once upon a time could have been the opener of (Princess) Diane von Furstenberg’s story, but a fiercely independent spirit and passion for women and the actual lives they live paved a different path. And it seems time has stood still for her famous wrap dress.

The Belgian-American designer, born Diane Simone Michelle Halfin to a Romanian father and Greek-born, Jewish mother — a Holocaust survivor — in 1946, met and married Prince Egon von Furstenberg by 1969 and dropped her title as she set out to make a name for herself. DVF, as she is known, is one of the only living designers recognized by their initials only.

It was not difficult for her to enter the world of fashion. Her access was complementary to her social ties and title by marriage, but it was her drive to be independent in the latter that paved the road to her many accomplishments.

In 1969, a young and pregnant newlywed, von Furstenberg made her way to New York and into the fashion club just as many other designers did — dragging a suitcase full of her ideas around to buyers and magazines. A meeting with Vreeland, then editor of Vogue — who liked her new approach to dressing women — would get her name on the fashion calendar. The wrap dress she has become famous for made its debut in 1974. Its success led to a cosmetics line and other licensing opportunities. By 1976, DVF and her wrap dress landed on the cover of Newsweek magazine, and the rest would be fashion history.

The robe-style silhouette which complimented the free-spirited zeitgeist of the time has since been inducted into The Metropolitan Museum of Art Costume Collection and The Smithsonian. Her single vision for changing the way women live has continued in her commitment to community and women’s rights across the globe.

Tracy Reese

Knowing how and when to pivot is an asset to longevity in the fashion industry, and designer Tracy Reese understands this, having endured many shifts in fashion’s fickle economy with a combination of family support, perseverance and passion.

The Detroit native and Parson’s alum established herself in fashion while still a student. From designing with Martine Sitbon, she started her own business in 1987, a moderately successful contemporary sportswear collection described by the designer in an interview with WWD at the time as “not basic, not classic either, but hopefully essentials.”

Reese became the essential go-to for many women when she used her eye for combining color and print with sustainable production to establish her eponymous line in 1997. The expansion came quickly, and her lower-priced Plenty label followed. More growth came in 2002 with resort, swimwear and home fashions collection — opportunities in licensing, brick-and-mortar and e-commerce led to global expansion and incorporation.

Like many American designers, Reese’s opportunity to dress former first lady Michelle Obama, the first Black woman in the White House, was a plus. Still, with a recession softening the business, she reconsidered what the brand she founded needed to be.

By 2018, Reese saw the expansion of “volume production” and change on the horizon. Her decision to pivot was poignant. She paused her business to reconsider the long-term vision for herself and her brand. In 2019, Reese moved her operation back to the manufacturing hub of her native Detroit, and “Hope for Flowers” was born. The collection is part of the slow fashion movement and embodies Reese’s signature style. But most importantly, Reese continues to stay ahead of the conversation. Her choice to become a part of Detroit’s manufacturing resurgence with ISAIC Factory is a partnership that incorporates positive social changes in a sustainable community-supported environment.

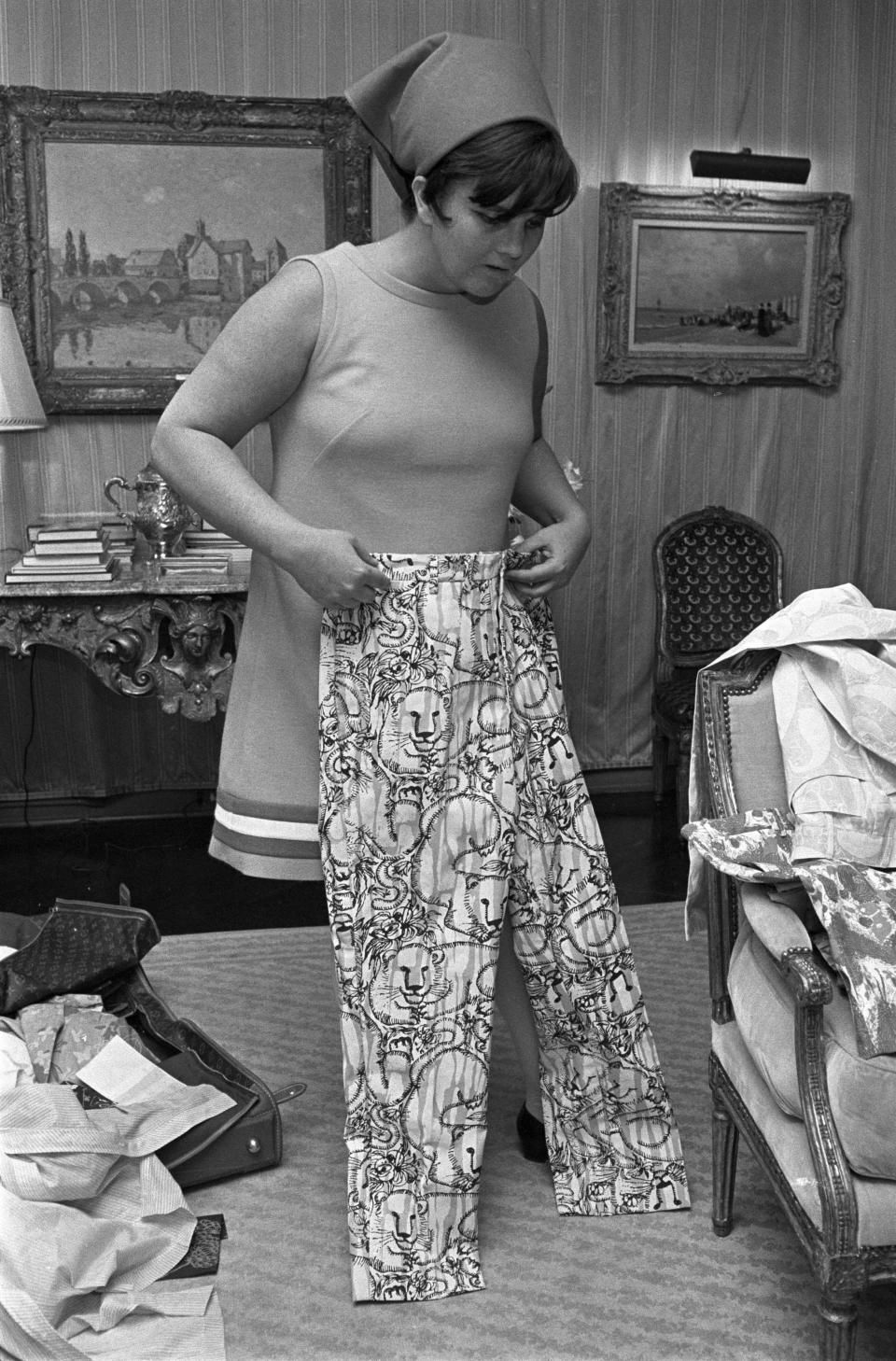

Lilly Pulitzer

Creating an iconic fashion brand can take years. Not so for Lilly Pulitzer, whose goal was not to start a fashion business. Tiring of the barefoot lifestyle and the endless parties of Palm Beach, Fla., she sought help and a doctor advised that she needed a sense of purpose. In 1959, the New York transplant and socialite opened a juice bar using the citrus from her husband Peter’s grove. As the business boomed, her juice-stained clothes led her to consulting with a dressmaker to create an easy, colorful printed shift dress to hide that occupational hazard. The resort colony’s newcomers raved about the vibrant dresses. In 1962, “the Lilly” was the dress to be seen in, thanks to Pulitzer’s former classmate, First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy, who wore a Lilly shift on a cover of Life magazine that year. “It took off like zingo,” the designer once explained.

Shifting from the citrus business to the clothing business, Pulitzer kick-started American resortwear and would come to define chic preppy style. A 1962 WWD interview with Pulitzer noted that the then-fledgling label never repeated its splashy, whimsical prints and described the line as “just right for sand, patio and at-home…a perfect combination for Florida’s playland.” The label quickly expanded beyond dresses. Pulitzer told WWD in 1968 that her signature pants were “cut with sympathy” to compliment herself and her consumer. Accessories, childrenswear and menswear were added to round out the Lilly Pulitzer concept.

Pushing sales of $343.5 million today, the label sells activewear, swimwear, home decor, gifts, sportswear and more. More than 65 years after the first store debuted in Palm Beach, the brand is available online and in more than 100 locations, including signature stores. But the business hit its share of choppy waters along the way. Although some of the initial success came from major department store distribution, the zeal of the Palm Beach lifestyle began to fade in 1969 and the colorful, fun aesthetic that made Lilly Pulitzer a preppy favorite was no longer trending in fashion. Attempts to sway with fashion’s ever-evolving tide changed the brands ethos and removed it from fashion’s purview. In 1984, Pulitzer, who had divorced her first husband and wed Enrique Rousseau years before, filed for bankruptcy. In 1993, the line was brought back by Sugartown Worldwide and then sold to Oxford Industries. Pulitzer acted as a creative consultant until her death in 2013. More than a decade later, the founder’s vivacious style is keeping the fun in fashion.

Launch Gallery: 10 Inspiring Women Designers in Fashion History

Best of WWD