This Woman Survived One Of The Deadliest Snake Attacks

This article is part of HuffPost’s Project Zero campaign, a yearlong series on neglected tropical diseases and efforts to fight them.

CHERANGAN, KENYA ― Walking home from a party in the evening light, Cheposait Adomo was unaware of the 6.5-foot black mamba snake in her path until it had coiled around her ankles and sunk in its teeth.

As Adomo screamed and pulled at the slithering knot that punctured her three times, she was unaware of the two other brown-colored mambas slithering over to provide backup.

“I felt the bites and then a burning sensation,” Adomo, a mother of five, said of the attack, which happened late last year near her hilly village of Cherangan, in Kenya’s West Pokot County, close to the Ugandan border.

In this poor and remote area, a three-hour drive along rocky switchbacks to the nearest city, most people run for their lives at the sight of what Adomo described as “very fierce snakes” that deliver deadly bites.

“We’ve heard anecdotal reports about black mamba bites causing respiratory death within 40 minutes,” said Dr. Robert Harrison, head of the Alistair Reid Venom Research Unit at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine.

“In a sub-Saharan African remote village context, that is often too quick between bite and death to get to hospital,” he added.

Adomo was saved from the other two mambas by a machete-wielding man who raced over and “cut them to pieces,” she said. But the three bites on her ankle were spreading a fiery sensation up her leg, and she started losing her vision.

“I fell down and people ran over to beat the snake around my legs so it would untie itself,” recalled Adomo, who thinks she’s around 40 years old.

As she started passing out, people gathered around her tried to stop the poison from circulating by using a traditional medicinal technique. They tied pieces of cloth around her wrists, ankles and knees and made cuts in her skin to insert small, porous stones. Then they loaded her onto a neighbor’s motorbike, hoping they’d see her again, and sent her down the long road on a 45-minute ride to the nearest hospital.

Luckily, staff there had the anti-venom Adomo needed and saved her life.

While it’s tough to get a firm number of snakebites, it’s estimated that a million people in Africa are bitten a year ― yet only a fraction of those are thought to seek treatment at clinics. Globally, an estimated 5 million people are bitten by snakes per year, causing 100,000 deaths. Another 400,000 are left permanently disabled or disfigured. In sub-Saharan Africa, snakebites kill around 30,000 people annually and lead to an estimated 8,000 amputations.

Doctors are trying to stamp out traditional treatments, like the one Adomo received in her village, because the practices can increase fatality rates for some snakebites and in all cases delay life-saving medical treatment. Given the right anti-venom, only between one and two percent of snakebite victims will die. Usually, these deaths happen when a person doesn’t get medical care in time, said Julien Potet, policy adviser on neglected tropical diseases for the French charity Doctors Without Borders.

Despite snakebites’ high rates of death and disability, experts say that in Africa it has been largely ignored by both the public and private sector. The hardest-hit victims are rural farmers, the “poorest of the poor,” says Potet. For many snakebite patients, a life-saving anti-venom costs more than their annual wage. But such high quality medicine is increasingly hard to find in rural Africa, and local clinics struggle to access it or even properly store it.

Put all this together, and it’s easy to see why so many people shy away from medical care.

“As long as the treatments will cost $50 to $100 per patient, the majority of victims will struggle” to pay, or even think about visiting the clinic, said Potet.

A current shortage of anti-venoms to treat African snakebites means that being bitten now is even deadlier than it was decades ago.

Until the early 1990s, “about 200,000 vials were used in Africa, and now it’s probably less than 30,000 or 40,000,” said Dr. Jean-Phillippe Chippaux, who has been studying snakes for over 40 years.

Because the average snakebite victim needs two doses, for 300,000 annual patients, “we probably need 600,000 vials in Africa each year,” he said.

A VICIOUS CIRCLE

A few years ago, the French drug company Sanofi Pasteur stopped making FAV-Afrique, one of the most effective anti-venoms for 10 types of African snakes. This was useful for cases where patients don’t know which snake bit them. But the treatment cost patients between $280 and $560, and Sanofi claimed it could no longer compete with the newer, cheaper and, in many cases, lower quality anti-venoms from Asia.

The company sold its last batch of FAV-Afrique in 2014, and the remaining supplies expired in 2016, leading to what Doctors Without Borders called a “snakebite crisis.”

Love HuffPost? Become a founding member of HuffPost Plus today.

But the problem is bigger than one drug. Sub-Saharan African governments and overseas aid donors have been mostly unwilling or unable to invest in the research and development of quality anti-venom at the local level.

In Kenya’s Kilifi County, where many snakebites occur, Royjan Taylor, who manages the Bio-Ken medical research snake farm in the coastal resort town Watamu, has witnessed the demise of pricey yet effective anti-venoms.

“A big problem has been that anti-venoms from places like India have been dumped into the African market,” he said.

“There are so many hospitals that have used these, which I can tell you are totally and absolutely useless.”

THE PRICE OF POOR ANTI-VENOMS

In countries like Ghana and Chad, the introduction of new anti-venoms led to mortality rates from snakebites rising from around two percent to between 12 and 15 percent. Given similar mortality rates for untreated snakebites, “that’s equivalent to not giving any anti-venom at all,” said Harrison, the venom researcher from the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine.

Over the past four years, Harrison and his colleagues have been searching for a safe new anti-venom to neutralize many different snakebites in Africa. They’ve done this by milking the venom of over 800 toxic snakes taken from Africa to Liverpool labs.

Their work also involves testing anti-venoms sold in Kenya that have never even been tested on animals. By identifying the substandard anti-venoms, “we can avoid so many unnecessary deaths,” Harrison said.

“If all countries in sub-Saharan Africa where snakebite is important would do the same, we could make sure that the ineffective anti-venoms were forbidden for human use,” he added.

In Kenya, victims dying from ineffective anti-venoms ― leaving families with huge hospital bills ― discourage people from treatment in medical wards rather than by the cheaper and closer traditional doctors.

“They have lost confidence in seeking western medicine in a hospital,” said Taylor, the Bio-Ken snake farm manager.

“Every couple of months a person has died from snakebite because they didn’t get treatment in time,” he added.

Through fundraising, Bio-Ken buys between 50 to 100 vials of anti-venom per year to treat poor victims for free. But the need is much greater, “about 20,000 vials for Kenya alone, at an absolute minimum,” said Taylor, who sees how death and disability from snakebite renders people living in poor rural communities destitute.

HOPE ON THE HORIZON

The World Health Organization is currently assessing anti-venom products aimed at the African market to weed out the duds. It is also considering putting snakebites back on its list of neglected tropical diseases.

Researchers say that snakebite is a much more immediate and deadly condition than many of the 18 conditions listed, which tend to affect the world’s poorest but lack funding and attention, and is more ignored.

It may come as a surprise that, in an age where advances in genetic cloning seem hum-drum, little has changed in developing anti-venoms since their discovery in 1894.

“It’s ridiculous. I can’t believe we’re spending money on Dolly the sheep and not this,” said Taylor.

Success in the snakebite world is small but significant.

Doctors Without Borders is researching anti-venoms in the Central African Republic and has seen large upswings in treatment there, as well as in Ethiopia and South Sudan. The African Society of Venimology, founded in 2012, is lobbying internationally and training medics locally, soon by video tutorial to increase its reach. In Burkina Faso, government subsidies for anti-venom have brought costs to patients down from $140 to $4.

In Kenya, the team from the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine is introducing snakebite motorcycle ambulances, to help especially patients bitten by mambas and certain cobras that can quickly stop breathing.

Adomo remembers little of the motorbike ― owned by a neighbor― that whisked her to the hospital.

“I lost my vision and memory and didn’t know what was happening until I was in the hospital,” she recalled.

“She was going into shock, she thought she would die,” said Dr. Michael Makari, who runs the hospital in Kacheliba where Adomo received care.

Today, people in her village light torches and fires at night and don’t walk in the dark to avoid the snakes. But having been so close to death, Adomo still shivers at the thought of these creatures.

“Now, I really fear snakes, and even seeing the tracks they’ve made in the sand,” she said.

This series is supported, in part, by funding from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. All content is editorially independent, with no influence or input from the foundation.

If you’d like to contribute a post to the series, send an email to ProjectZero@huffingtonpost.com. And follow the conversation on social media by using the hashtag #ProjectZero.

More stories like this:

He Treated The Very First Ebola Cases 40 Years Ago. Then He Watched The World Forget.

Rabies Kills 189 People Every Day. Here’s Why You Never Hear About It.

When Bullets Fly, These Medics Grab Their Packs And Treat Patients On The Run

This Man Went Abroad And Brought Back A Disease Doctors Had Never Seen

A Parasite Attacked This Dad’s Brain And Destroyed His Family

Also on HuffPost

Lymphatic Filariasis

Onchocerciasis

Chagas

Dengue

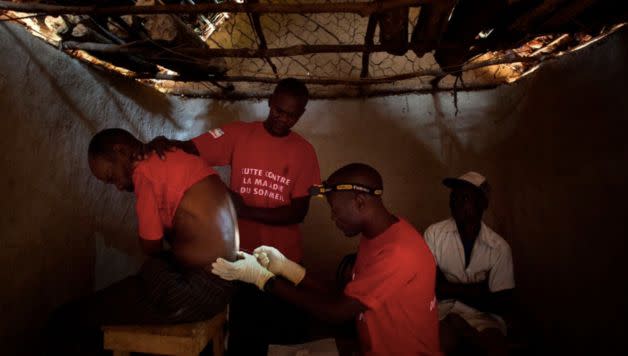

Human African Trypanosomiasis

Leishmaniasis

Trachoma

Rabies

Leprosy

Schistosomiasis

![Schistosomiasis is a chronic disease that causes gradual damage to internal organs. Symptoms include <a href="http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs115/en/" target="_blank">blood in urine</a>, and in severe cases, kidney or liver failure, and even bladder cancer. Around 20,000 people die from it each year. Transmitted by parasites in infested water, the disease largely affects poor, rural communities in Africa that lack access to safe drinking water and sanitation. “[People] get it as kids bathing in water,” Sandrine Martin, a staff member for the nonprofit <a href="http://www.malariaconsortium.org/pages/who_we_are.htm" target="_blank" data-saferedirecturl="https://www.google.com/url?hl=en&q=http://www.malariaconsortium.org/pages/who_we_are.htm&source=gmail&ust=1480609103751000&usg=AFQjCNG03VPF1XL5zli4__XAjDWpDmBOvw">Malaria Consortium</a> in Mozambique, told HuffPost. “But the symptoms, like blood in the urine, only develop later ― and then people tend to hide it because it’s in the genital area.”](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/9f9As.sw0iNn_ENR93iBhA--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MA--/https://img.huffingtonpost.com/asset/5845a09e1700002500e7dd42.jpg)

Chikungunya

Echinoccosis

Foodborne Trematodiases

Buruli Ulcer

Yaws

Soil-Transmitted Helminth

Taeniasis

Guinea Worm

This article originally appeared on HuffPost.