Trump Wouldn’t Be The First Republican To Cry 'Voter Fraud' To Contest A Loss

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

President Donald Trump’s plan for election night and the immediate aftermath is clear: If he loses, or looks headed for a loss, he will lie and claim he was cheated. He will look to reverse the results with lawsuits, by pressuring state level-Republicans or through any other method he and his allies can think of.

Trump has seeded this plan all year with his torrent of lies about absentee and mail-in voting and his hyperventilating inventions about widespread voter fraud. But like most of the worst excesses of the Trump era, the seemingly outlandish plot to steal the election on phony claims of voter fraud predates the president himself. The Republican Party has been pushing misinformation about voter fraud for decades as it also works to limit access to the polls. Some GOP lawmakers have even used these claims to try to remain in office in spite of losses. Trump’s just being more transparent about it.

Since 2000, Republican politicians, lawyers, nonprofits and partisan media outlets have fomented false accusations of voter fraud in order to promote policies meant to make it harder to vote for Democratic Party-leaning constituencies, like racial minorities and college students. When Republicans won control of states in the past two decades, they quickly moved to impose new voting restrictions, close polling locations and remove voters from the rolls. All of this was based on disproven claims of mass voter fraud. And when they lost elections, like in the 2008 presidential race, they blamed that on unfounded voter fraud conspiracies.

As 2016′s Election Day neared, Trump pointedly refused to commit himself to accepting the results. After he won, he still made baseless claims of voter fraud. To this day he still lies and claims he won the popular vote, “if you deduct the millions of people who voted illegally.”

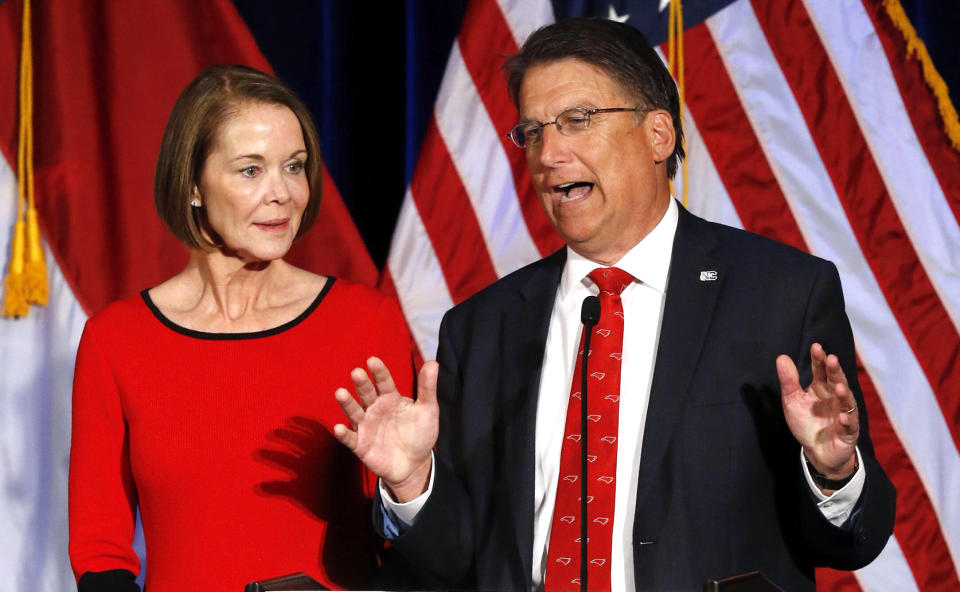

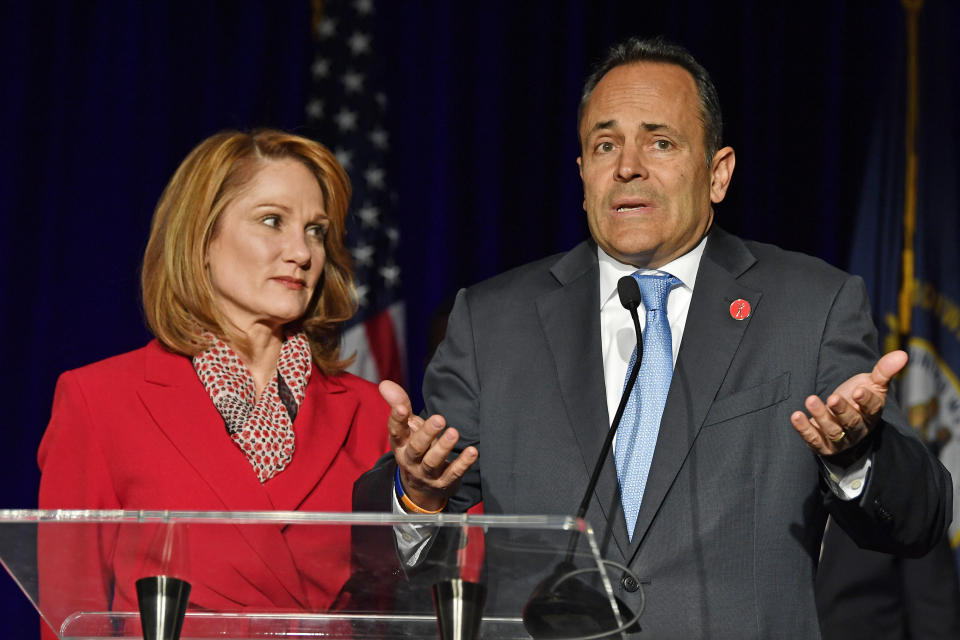

Trump didn’t have to contest the election result formally last time. This time, he might. And if he does, he’s likely to follow the same playbook as two former GOP governors who refused to concede based on unsubstantiated claims that the vote in their states wasn’t fair. Former North Carolina Gov. Pat McCrory and former Kentucky Gov Matt Bevin managed to undermine faith in the election and their own credibility ― then ultimately were forced to concede defeat.

“This is a song we’re hearing sung once again this year,” said J. Sailor Jones, campaign director for the nonprofit Democracy North Carolina.

North Carolina: 2016

As election night ended four years ago, McCrory trailed Democrat Roy Cooper by about 5,000 votes out of 4.7 million cast. Cooper’s lead emerged after the results of a block of 90,000 ballots from Durham County were reported just before midnight.

McCrory refused to concede, crying voter fraud. He and the state Republican Party would go on to falsely accuse hundreds of North Carolinians of voter fraud as rumors swirled that the accusations could lead the GOP-controlled Legislature to overturn the election and hand him a second-term.

McCrory’s post-election move to claim he lost election due to voter fraud wasn’t premeditated like Trump’s is today. Instead, he chose to do so after he lost.

His campaign immediately expressed “grave concerns over potential irregularities in Durham County.” Local North Carolina Republican activists, at the direction of the McCrory campaign’s law firm, filed a slew of protests with county elections boards to contest the result.

McCrory’s protests accused more than 600 individual North Carolina voters of committing fraud. Most of the protests alleged double-voting, illegal voting by felons and absentee voting fraud. As McCrory’s campaign pushed these protests, they ran a public relations campaign that made further wild accusations of dead people voting and claimed new explosive revelations were going to turn the race around.

In one instance, McCrory’s campaign declared, “A massive voting fraud scheme has been uncovered in Bladen County,” where more than a third of residents are Black.

The complaint focused on an event local activists helped 250 absentee voters fill out their ballots while also serving as witnesses. This was perfectly legal at the time, but McCrory’s team claimed it was an “absentee ballot mill.” Similar protests were filed in other counties where groups helped witness absentee ballots submitted by Black voters.

“There’s a direct correlation between the counties that were selected for challenges and the active participation of black political action committees,” Rep. G.K. Butterfield (D-N.C.) said after attending a hearing on alleged voting irregularities in Halifax County. “This is targeting the African-American community and their participation in the election.”

Amid the protests by McCrory’s campaign, political observers started to discuss a state law that allowed the state Legislature to overturn the results of an election if they deemed it too corrupted. Such a move by the Legislature, which featured a Republican supermajority at the time, was “not reviewable” by the courts.

The law had only been used once, when the Legislature chose the winner in a school superintendent race in 2004 after a voting machine malfunction lost 4,500 votes, making it impossible to know the real winner. Speculation became rampant that McCrory’s fraud allegations were designed to get the Legislature to intervene.

McCrory’s strategy, though, was plagued by one big problem: Almost every accusation of voter fraud was found to be false by county boards of elections, each of which had two Republican commissioners and a Democratic one.

First, the Durham County board rejected McCrory’s request for a recount when it found nothing wrong with the county’s late reporting of 90,000 ballots. The campaign asked the state Board of Elections to intervene and take over from the county boards the review of voter fraud allegations. The state board rejected that request in most cases, while agreeing to look at the protest of the vote in Bladen County. It found no sign of foul play.

McCrory’s lawyers also prodded local Republican officials to file sloppily researched protests claiming voter fraud against more than 600 people, according to a report by Democracy North Carolina.

Just 30 of the 600-plus accusations turned out to be accurate. But even these cases mostly involved parolees who were misinformed that they could vote ― no mass voter fraud scheme was uncovered.

Many of the local Republicans who filed the protests would later complain that they “got screwed,” were “disappointed” or “victimized” or “left hanging” by the McCrory campaign, according to the Democracy North Carolina report.

Some of the voters falsely accused of fraud were even angrier, especially those who saw themselves named in their local papers. A number of them filed a libel lawsuit against McCrory.

“Now that I know what happened to me was wrong, I am fighting back,” Gabriel Thabet, a registered Republican falsely accused of voter fraud, wrote in the Greensboro News & Record. “I see this effort to invalidate my vote for what it is. It was intimidation, plain and simple. And the national effort to undermine our confidence in the electoral system with baseless allegations of noncitizens voting is the same thing.”

As the month of November ended, provisional and late-counted absentee ballots had pushed Cooper’s lead to over 10,000 votes, above the threshold for a recount. McCrory’s campaign said they’d drop their request for a statewide recount if the state board performed a machine recount for Durham County and it turned up no change. When Durham’s machine recount revealed no change , McCrory conceded the election.

At the end of the day, McCrory’s efforts were hamstrung by the Republican commissioners on the county boards of elections who did not simply see their job as partisan rubber stamps. The Republican Legislature also never moved to intervene as McCrory failed to turn up any evidence of intentional fraud.

A well-publicized voter fraud case did mar North Carolina’s 2018 election, and it involved misconduct by a Republican ― a campaign consultant named McRae Dowless. He was found to be running an actual absentee ballot mill to elect Republican Mark Harris in the state’s 9th Congressional District. Dowless had acted as one of McCrory’s protest filers in 2016.

Harris looked to have won the House seat, but the wrongdoing by Dowless caused that result to be invalidated. The state’s election board scheduled a special election for September 2019, which Republican Dan Bishop won.

Kentucky: 2019

Last November in Kentucky, Bevin wasted no time challenging results showing him losing reelection to Democratic Andy Beshear by about 5,000 votes.

“[T]here have been more than a few irregularities,” Bevin told his supporters as he refused to concede on election night. He claimed, with no evidence, that these irregularities, “have been substantiated.”

Again with no evidence, he insisted, “We know there have been thousands of absentee ballots that were illegally counted. That is known.”

It wasn’t.

He also questioned whether ballots were counted in one county, said that the 2018 scandal involving Dowless in North Carolina could be happening in Kentucky, and claimed people were turned away from polling places. Again, he presented no evidence, save for his own intuition.

“Honestly, I don’t think his accusations of voter fraud were all that clear,” said state Sen. Morgan McGarvey the chamber’s Democratic leader. He speculated that Bevin was simply “raising the idea that there could be voter fraud.”

Yet some talk still surfaced in the national and local press that Bevin could, theoretically, push the Republican-led Legislature to intervene and invalidate the election based on his made-up claims of fraud. Kentucky Senate President Robert Stivers (R) suggested that it was possible the Legislature may need to intervene.

“There’s less than one-half of 1%, as I understand, separating” Bevin and Beshear, Stivers said. “We will follow the letter of the law and what various processes determine.”

As evidence of any fraud remained elusive, Stivers and other GOP leaders in the state pushed the governor to put up or shut up.

“It’s time to call it quits and go home,” Stivers said two days after he suggested a possible legislative intervention.

U.S. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, the dean of Kentucky’s Republican Party, offered his assessment a few days after the election, and it didn’t help Bevin’s cause. The governor “had a good four years” in office, McConnell said, adding that he was “sorry Matt came up short.”

On Nov. 13, a group run by Bevin appointee Erika Calihan threw together a slapdash press conference to lay out claims of voter fraud and election irregularities. Bevin promised to attend the event when he promoted it on his social media accounts, but then did not.

Calihan’s unsubstantiated claims did little more than reveal that there was no evidence of fraud save for unfocused conspiracy theories.

The state conducted an automatic recanvass of the vote required by how close the election was Nov. 14. It changed one vote. Bevin conceded quickly after the recanvass.

“I do point to this example as a model for the country should Trump refuse to concede,” Josh Douglas, an election law professor at the University of Kentucky College of Law, said. “It’s really important for people of the candidate’s own party to not allow these allegations of election fraud without any evidence to continue to be the storyline.”

Trump: 2020

The examples of McCrory and Bevin show that Trump’s effort to manipulate the election with false claims of voter fraud to potentially steal it is not an aberration, but an extension of the Republican Party’s mindset and behavior in recent years.

But they also show that such a plan requires a huge number of actors to bend to the will of the perpetrator.

McCrory could not get the Republican-led county or state boards of elections to rule in his favor. The Kentucky Legislature ditched Bevin once it turned out he had no evidence for his fraud claims.

Trump will need Republican-led state legislators, Republican members of Congress and the Republicans on the Supreme Court to back his claims of fraud if he hopes to even come close to overturning a result favoring former vice president Joe Biden. That relies on a lot of people choosing to act as Trump wants them to.

The recent examples show how hard that is. Then again, controlling the presidency is far more important than a governor’s mansion.

Love HuffPost? Become a founding member of HuffPost Plus today.

This article originally appeared on HuffPost and has been updated.