He Treated The Very First Ebola Cases 40 Years Ago. Then He Watched The World Forget.

This article is part of HuffPost’s Project Zero campaign, a yearlong series on neglected tropical diseases and efforts to fight them.

KINSHASA, Congo ― In early 2014, few people worried that the Ebola virus, which is up to 90 percent fatal, would pose a global threat. So the World Health Organization sent shockwaves around the world when it announced that Ebola was spreading out of control in West Africa.

Before the epidemic was over two years later, it had killed thousands of people. They died in terrifying and painful ways, often passing the disease on to family members before and even after death. Doctors and aid workers died, people who should have been able to stay safe while offering care.

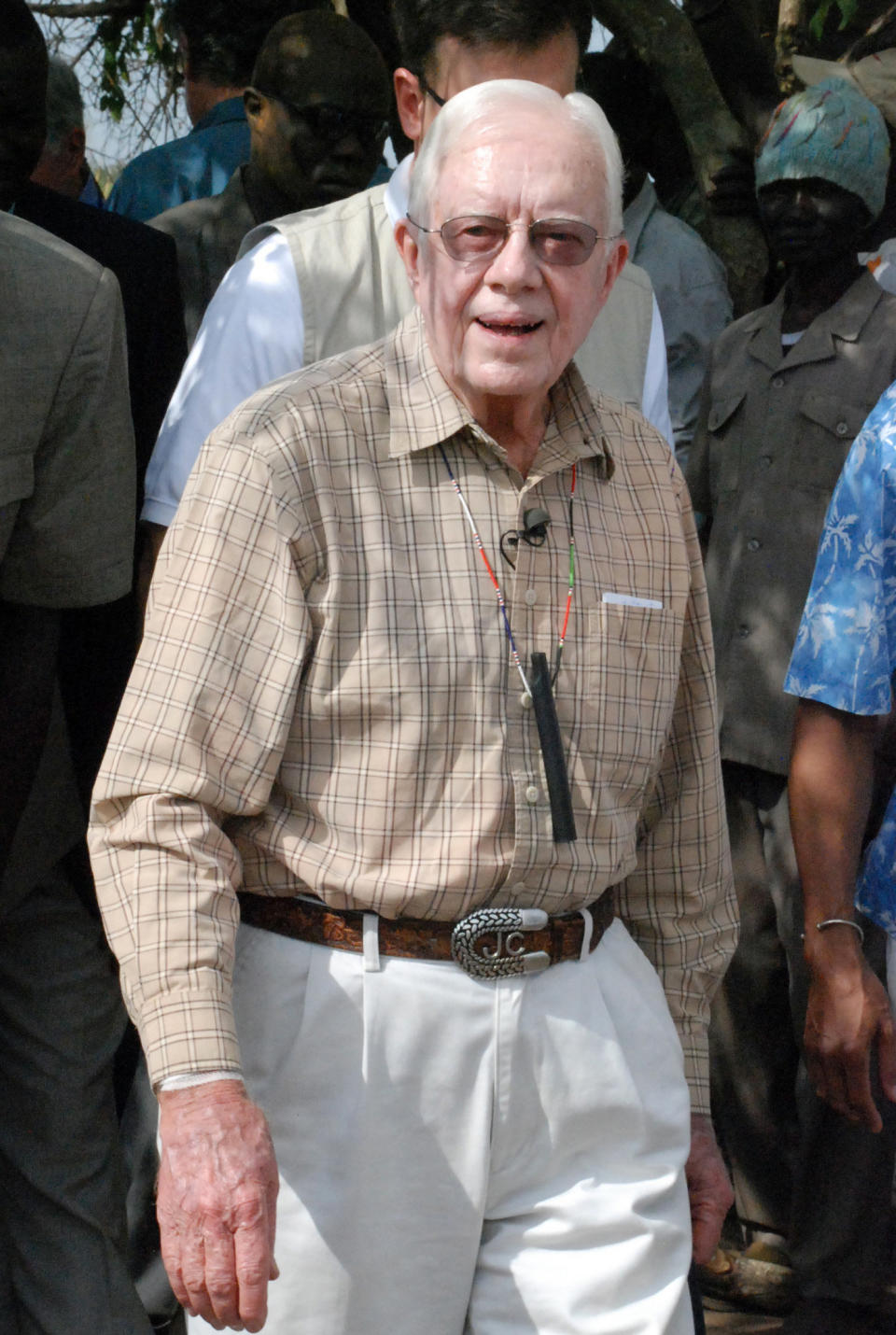

But not everyone who is exposed to the Ebola virus, which spreads through contact with blood or other bodily fluids, falls ill. Such is the case of Dr. Jean-Jacques Muyembe-Tamfum, who in 1976 became the first scientist to come into contact with Ebola and survive.

The Congolese virologist, now 74, placed himself square in the path of the disease as he worked in harrowing and hazardous conditions to identify what was killing some of its earliest victims.

“I am like Johnnie Walker,” he quipped, referencing the well-known Scotch whisky slogan, “Born 1820 ― Still going strong.” Muyembe giggled as he strode around his office imitating the brand’s iconic “Striding Man.”

It’s a joke in service of a very serious message from a doctor who has spent years battling the worst viruses. Don’t make the same mistake, he warns, that the world made with Ebola when it first arose. Don’t ignore the threat because it seems far away.

Muyembe, who now leads the Democratic Republic of Congo’s National Institute for Biomedical Research, had been home from studying in Europe just a few years when he received a phone call in 1976 that would change his life forever.

“The minister of health rang and said, ‘There’s a mysterious disease that’s killing people at the Catholic mission in Yambuku in Equateur province. I’m going to send you there to find out the cause.’ I was the country’s only virologist,” Muyembe recalled.

The mission hospital was more than 600 miles northeast of the capital city of Kinshasa, deep in thick forest. Muyembe set off overland in a jeep with a military colonel who was also an epidemiologist. It was “a real adventure,” he said. All they were told was that there was a suspected outbreak of yellow or typhoid fever.

But when they arrived in Yambuku, the hospital was deserted. They went to sleep at the mission and woke to a very different scene.

Three nurses and one woman had died at home overnight, and the hospital was now full of patients ― some pushed there on bicycles, many feverish ― after word had gone round that doctors had arrived from Kinshasa.

Muyembe examined and drew blood from the sick and dissected the dead to take tissue samples ― all with bare hands. Later, he would shudder at the thought of how much contact he’d had with feverish patients, many of whom didn’t stop bleeding after he withdrew the needle or scalpel.

“The blood would pour out all day. My hands were covered in blood. I didn’t have gloves,” he said.

Muyembe thinks that what saved him from death that day, and the many others when he handled infected samples with no protection, was his speedy request for soap and water. But luck must have played a role too.

When a nun fell ill ― with fever and red marks on her body ― Muyembe and his colleague told the mother superior that they wanted to take the samples they’d collected and the sick nun back to Kinshasa. The nun initially refused to go ― she didn’t want the community to think she was running away ― but she relented after Muyembe insisted. Another sister accompanied her on the journey to Kinshasa, so they were a group of four squeezing together in various planes and cars.

“I was always next to her,” Muyembe remembered, still looking relieved decades later at the thought of his close brush with death.

The samples from Yambuku, including the nun’s, were sent from Kinshasa to a lab in Belgium, where scientists initially thought they showed the Marburg virus, which causes another hemorrhagic fever found in Congo and neighboring Uganda.

Meanwhile, when the nun, her traveling companion and a nurse who had treated her in Kinshasa all died from the same sickness, and the epidemiologist who had gone with him to Yambuku developed a fever, Muyembe panicked. He quarantined himself in the garage at his home so as not to infect his wife and children. He couldn’t stop thinking about the test tubes full of blood samples that he had brought home briefly after returning from Yambuku.

“It was terrible because the assistant medic who had come with me sent me a message saying, ‘Ah, I am sick,’ and then poof! He was dead. The nun we brought with us had died and had contaminated another nun and a nurse. I was very afraid,” Muyembe said.

He finally got a call from Belgium that the virus wasn’t Marburg but a previously unknown hemorrhagic fever. Researchers later named it Ebola, for the river that runs through Yambuku. It was after this call ― and the death of his fellow scientist ― that Muyembe destroyed the lab samples, terrified of further contamination.

Nearly 40 years later, when Ebola hit West Africa, Muyembe was surprised by the lack of research into the virus and the poorly coordinated global and local response.

“It really was chaos,” he said. “People thought it was just something that affected East and Central Africa, so they hadn’t even studied it and weren’t prepared.”

Muyembe had worked on research into a possible vaccine nearly two decades earlier, but it was only when Ebola briefly touched Europe and the United States in 2014 that he finally saw scientists start to take this killer seriously.

During Congo’s third Ebola outbreak in 1995, the experienced virologist had transfused blood from people who had recovered from Ebola to a group of patients infected with the virus. Of the eight patients who received the transfusions, seven survived ― a result that Muyembe quickly passed on to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the U.S.

“We kept saying, ‘Antibodies do protect.’ But for 20 years, this virus, and its treatment, was neglected,” he said. In late 2016, an experimental vaccine – developed principally in response to fears of Ebola being used as a bioterrorism agent – was shown to provide 100 percent protection against the virus. It arrived too late for the 11,000 people who died in the 2014 outbreak.

More recently, Muyembe has watched scientists scramble to stop the Zika virus once it began affecting wealthier countries. The virus is named for a forest in Uganda, where it was first found in 1947.

“Because it was an African disease, we neglected it. But with climate change and modern transport, the insects will travel to Brazil, to Europe,” he said.

There are other diseases that could devastate whole cities, countries or regions of the world, Muyembe warns.

Love HuffPost? Become a founding member of HuffPost Plus today.

So-called neglected tropical diseases affect over 1 billion people worldwide, mainly in poor parts of Africa, Asia and Latin America. Some of these diseases ― echinococcosis, dengue and Chagas, for example ― have already infected people in the U.S. in small numbers. But they attract very little attention in Western media and garner limited research funding.

“I wish I could say that onchocerciasis would make everyone in the world blind, because then we’d have a vaccine,” said Muyembe of a disease otherwise known as river blindness, which threatens up to 14 million people in Congo.

“We call them neglected diseases because they come from underdeveloped countries,” he said. “But these neglected diseases can become a threat to developed countries. With travel and everything we have now, the world has become a village.”

Our world needs better research and monitoring aimed at African countries, Muyembe warned, because that’s where many diseases start. And if they’re allowed to develop, “they will be like Ebola, which came from Central Africa, went to West Africa and then suddenly was threatening the U.S. and Europe.”

Muyembe is also determined to raise up the next generation of Congolese researchers to continue his legacy. “We must train the young people,” he said, slapping two young researchers on the back. Like him, they earned their Ph.D.s in Europe and then returned home to help.

Despite cheating one of the world’s most deadly diseases and plenty of other rare illnesses since, he too plans to keep fighting. “The most important thing in dealing with a lot of these diseases is washing your hands,” he said with a fatalistic shrug.

What frightens the doctor more than staring death in the face is retiring and dying of boredom.

“I must continue working,” Muyembe said, straightening his white coat and rushing off to his next appointment at the lab.

This series is supported, in part, by funding from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. All content is editorially independent, with no influence or input from the foundation.

If you’d like to contribute a post to the series, send an email to ProjectZero@huffingtonpost.com. And follow the conversation on social media by using the hashtag #ProjectZero.

More stories like this:

This Man Went Abroad And Brought Back A Disease Doctors Had Never Seen

Rabies Kills 189 People Every Day. Here’s Why You Never Hear About It.

A Parasite Attacked This Dad’s Brain And Destroyed His Family

Volunteers With No Medical Training Are Fighting Diseases The World Ignores

Also on HuffPost

Lymphatic Filariasis

Onchocerciasis

Chagas

Dengue

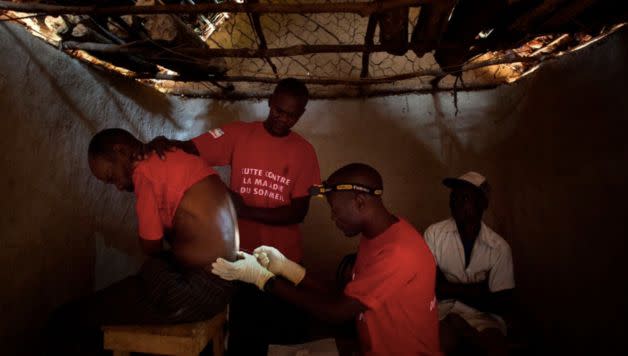

Human African Trypanosomiasis

Leishmaniasis

Trachoma

Rabies

Leprosy

Schistosomiasis

![Schistosomiasis is a chronic disease that causes gradual damage to internal organs. Symptoms include <a href="http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs115/en/" target="_blank">blood in urine</a>, and in severe cases, kidney or liver failure, and even bladder cancer. Around 20,000 people die from it each year. Transmitted by parasites in infested water, the disease largely affects poor, rural communities in Africa that lack access to safe drinking water and sanitation. “[People] get it as kids bathing in water,” Sandrine Martin, a staff member for the nonprofit <a href="http://www.malariaconsortium.org/pages/who_we_are.htm" target="_blank" data-saferedirecturl="https://www.google.com/url?hl=en&q=http://www.malariaconsortium.org/pages/who_we_are.htm&source=gmail&ust=1480609103751000&usg=AFQjCNG03VPF1XL5zli4__XAjDWpDmBOvw">Malaria Consortium</a> in Mozambique, told HuffPost. “But the symptoms, like blood in the urine, only develop later ― and then people tend to hide it because it’s in the genital area.”](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/9f9As.sw0iNn_ENR93iBhA--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MA--/https://img.huffingtonpost.com/asset/5845a09e1700002500e7dd42.jpg)

Chikungunya

Echinoccosis

Foodborne Trematodiases

Buruli Ulcer

Yaws

Soil-Transmitted Helminth

Taeniasis

Guinea Worm

This article originally appeared on HuffPost.