The Secret To Lower Premiums In The GOP Health Plan Is The Really Crappy Coverage

If there was a bright spot for Republicans in Monday’s dismal Congressional Budget Office analysis of their health care bill, it was one of the findings on insurance premiums for people who buy coverage on their own.

On average, the nonpartisan CBO found, premiums for the typical insurance plan would be 20 percent lower than if the Affordable Care Act were still in place.

Republican leaders were quick to highlight that as proof they would make insurance more affordable.

But analysts at the nonprofit Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation have crunched the numbers and come to a very different perspective on what the Senate Republican bill would do.

People who now buy insurance on healthcare.gov or a state exchange like Covered California would have to pay 74 percent more on average to get equivalent coverage, Kaiser’s analysts found.

That finding doesn’t mean the Republicans are lying. It does mean that the Republicans aren’t telling the full story about why premiums would come down 20 percent under their plan ― and what it would actually mean for people buying coverage.

Simply put, if Republicans get their way, then insurance policies will tend to cover less care, and fewer people with serious medical problems will be carrying insurance.

The Better Care Reconciliation Act, the bill that Senate GOP leaders released last week, would make several changes affecting people buying coverage on their own. Arguably the most important among these would be a change to the federal financial assistance available to these consumers.

Today, thanks to the Affordable Care Act, people buying insurance through one of the exchanges can get tax credits that reduce their premiums by hundreds or even thousands of dollars a year. The tax credits taper off as income rises, cutting out altogether at 400 percent of the poverty line, or $98,400 for a family of four.

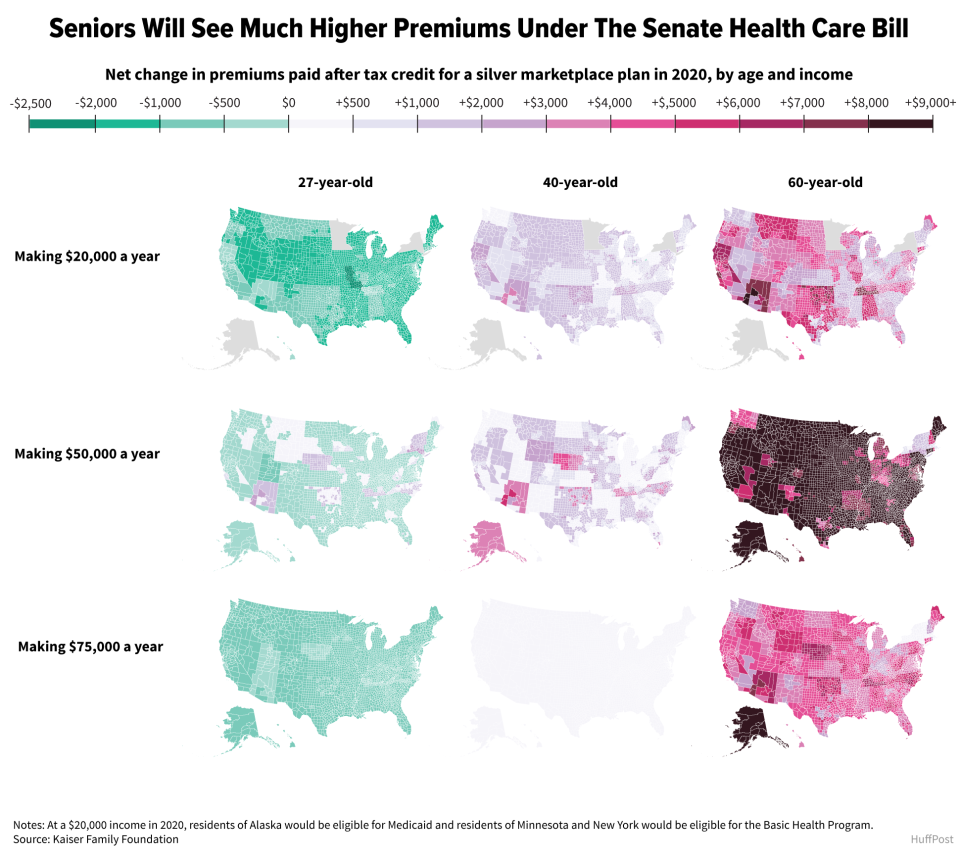

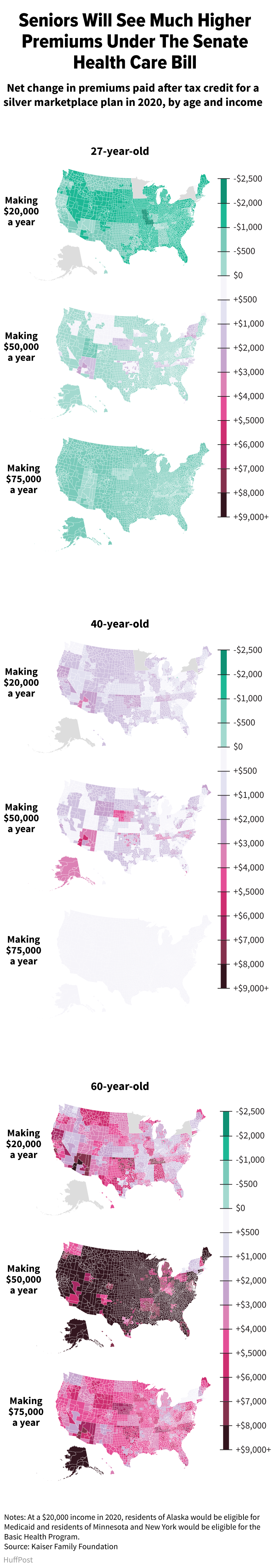

The Senate bill would preserve that same basic structure, but it would reduce the amount of money available ― cutting off assistance at 350 percent of the poverty line, eliminating extra subsidies that reduce out-of-pocket spending for lower-income consumers and tweaking the formula so that young people get relatively more assistance but older people get relatively less. That last change is particularly important because, separately, the proposal allows insurers to vary premiums more by age ― charging more to the old and less to the young.

A large portion of the people buying coverage on their own do so without the help of tax credits, in most cases by purchasing coverage directly from insurers. For them, changes in financial assistance are mostly irrelevant. But for everybody else buying coverage on his or her own, those tax credits matter a lot.

The precise effects would vary widely from person to person and place to place and, as is almost always the case with health policy, some people would end up better off.

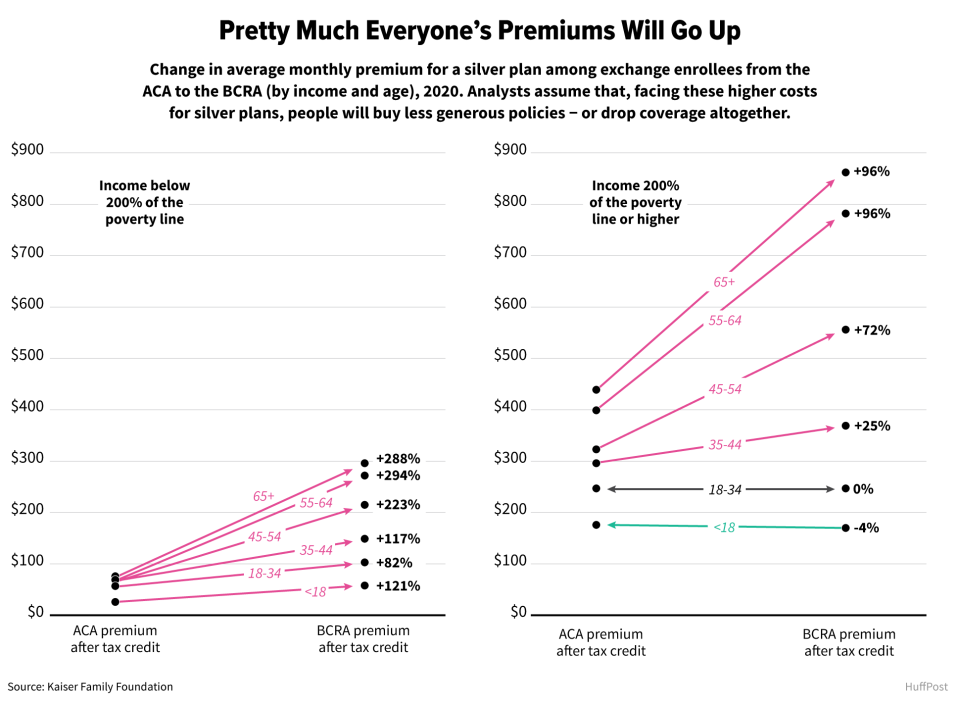

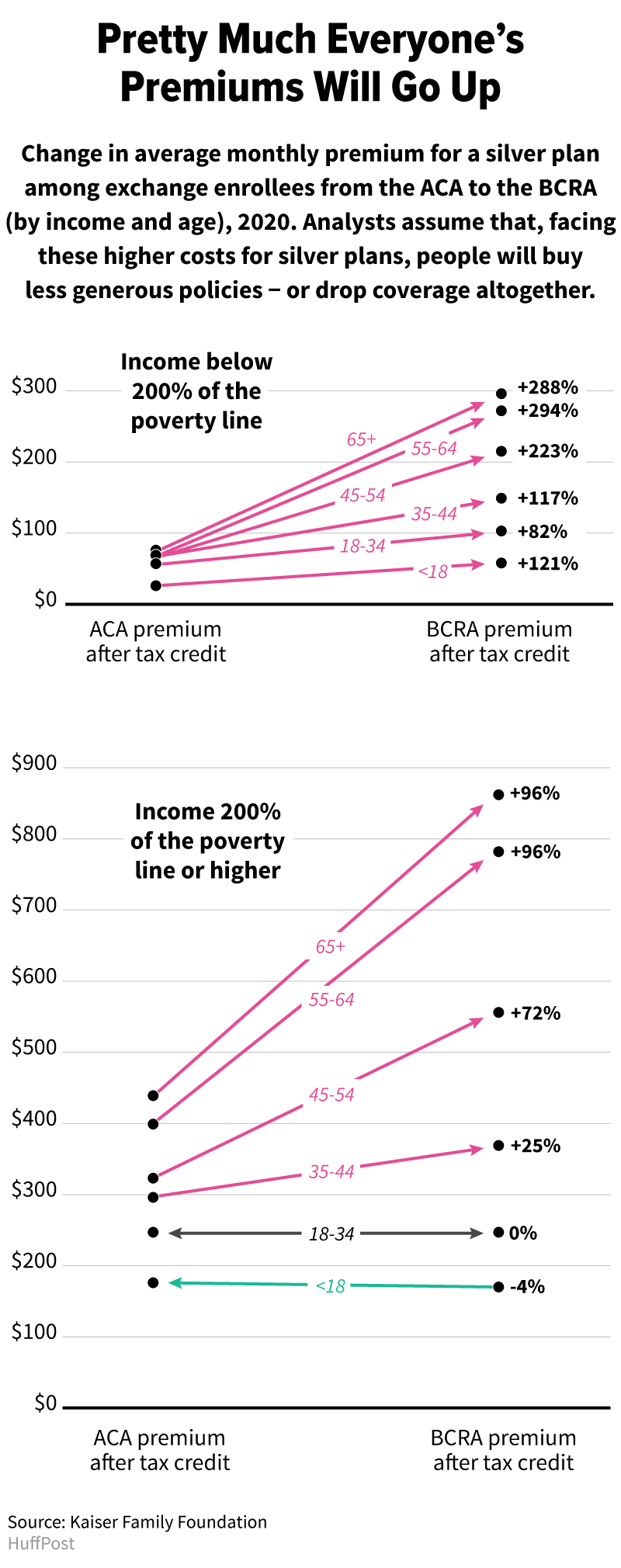

But when Kaiser’s analysts broke up the population into 14 groups, representing different incomes and ages, they found that only one group (younger than 18 with an income more than twice the poverty level) could actually get the same level of benefits for less money ― and even then, it was an average savings of just 4 percent, with monthly net premiums for this group dropping from $176 to $170.

Other groups were in line for increases, in some cases very large ones.

By far the worst off were the oldest consumers, particularly those with the lowest incomes. Americans near retirement age and living close to the poverty line could, according to the Kaiser analysis, expect to pay $272 a month rather than $69 under the ACA ― nearly four times as much.

“I think it’s fair to say that most people in the individual market today would be worse off,” Cynthia Cox, a Kaiser policy expert and co-author of the report.

The idea that premiums for similar plans would be higher, not lower, if a Republican health plan becomes law is consistent with the findings of other researchers, including Loren Adler and Matthew Fiedler of the nonprofit Brookings Institution think tank, who analyzed counterpart GOP legislation in the House and found that it, too, raised the price of equivalent coverage.

Of course, consumers facing such steep increases usually wouldn’t ― and in many cases couldn’t ― pay them.

The ones facing the steepest increases would in some cases opt not to get insurance at all, which means that older people would be dropping coverage even as some young people would be picking it up.

Other consumers would keep getting coverage, but in order to afford premiums within their means they’d have to take policies with higher out-of-pocket costs in the form of bigger co-payments and deductibles, or plans without key benefits like mental health coverage, which Obamacare mandates but the Republican plan would make optional, albeit at each state’s discretion.

And so insurance would end up cheaper on average (20 percent cheaper, by the CBO’s reckoning) because it would become weaker ― although, as yet another Kaiser study found, many people would still pay more because they’d be losing so much financial assistance. Older consumers, in particular, would take a difficult hit.

The Senate bill’s push towards less comprehensive coverage is not an accident. Many conservatives believe, rightly or wrongly, that exposing people to higher out-of-pocket costs will ultimately make health care less expensive. As this argument goes, giving people “skin in the game” will make them price-conscious when they seek out care ― and maybe give them reason to think twice about care they might not need.

But that’s not how Republicans have promoted their agenda for the last few years. Instead, they attacked Affordable Care Act plans as too expensive and vowed, as President Donald Trump did on the campaign trail, to create a system that would offer “great health care at a tiny fraction of the cost.”

The new analysis of the Republican bill shows how empty that promise was. For a fraction of the cost, you also get a fraction of the health care.

This article has been updated to include information from the second Kaiser study.

Love HuffPost? Become a founding member of HuffPost Plus today.

Also on HuffPost

1912

1935

1942

1945

1960

1965

1974

1976

1986

1988

1993

1997

2003

2008

2009

2010

2012

This article originally appeared on HuffPost.