How Past Bombshell Reports Paved The Way For The Mueller Report

The showdown over public disclosure of special counsel Robert Mueller’s report is the latest in a line of fights over important Washington reports that threaten to reveal too much about the U.S. government or the people who run it.

Since the probe into President John F. Kennedy’s assassination inaugurated our era of official investigative reports, government officials have clashed over what the public has a right to know. Some famous government reports, like the Senate Intelligence Committee’s investigation into the George W. Bush administration’s torture policy, remain largely hidden from the public.

Democrats are fighting to ensure that the Mueller report into Russian meddling in the 2016 election and the Trump campaign’s potential involvement doesn’t meet the same fate. The House Judiciary Committee authorized the use of subpoenas to obtain the unredacted Mueller report from the Department of Justice on Wednesday. The move by investigators put Congress into a direct fight with the executive branch over the report and its contents, little of which has been made available to the public.

Past fights over disclosure of Washington reports do not provide a roadmap to how the Mueller report clash will play out. Each disclosure fight has played out under its own set of rules, in its own political environment and with its own group of actors. The fight over the Mueller Report will play out under a set of regulations that hasn’t previously spurred this kind of clash.

What the history of these fights over official reports does show is that, when tested by scandal, law-breaking or tragedy, the legitimacy of democratic government rests on the broadest disclosure possible.

The Assassination of John F. Kennedy

Lee Harvey Oswald assassinated President John F. Kennedy at Dealey Plaza in Dallas, Texas on November 22, 1963, shocking the nation. Or, at least, that’s what they want you to think.

Newly inaugurated President Lyndon Johnson appointed a grand commission of the nation’s most important political figures led by Supreme Court Chief Justice Earl Warren to get to the bottom of how U.S. intelligence failed and whether Oswald acted alone. (The commission was modeled off of the presidential commission led by Justice Owen Roberts that investigated the Pearl Harbor attack.) And, in order to quell public concerns about government secrecy, Johnson’s attorney general Nicholas Katzenbach insisted the commission issue a public report.

The commission issued an 888-page report and an additional 26 volumes containing hundreds of depositions and thousands of pieces of evidence. The report concluded that Oswald was the lone gunman who killed Kennedy with two shots from the rear. There was no second shooter on the grassy knoll, no grand conspiracy and no further explanation. Jack Ruby’s murder of Oswald on live television made sure of that last point.

The establishment of a commission and the issuance of a public report came to define how a democratic political system should address a calamitous event or controversial investigation. But not everyone felt that way at the time.

Some commissioners didn’t fully agree with the report’s conclusions. Journalists and assassination obsessives subsequently uncovered what was missing from the report.

Warren, a close friend of the Kennedys, barred the commission from examining photos of Kennedy’s body out of respect for his family. The report failed to mention that the CIA and FBI had both kept tabs on Oswald leading up to the assassination. And it never explained why Oswald did it (probably because Ruby killed him before he could say anything). Another problem undermining the commission’s conclusion, that a commission lawyer would later point out, was that none of its deliberations were open to the public. A couple of years later polls showed that most Americans did not believe the commission’s conclusion.

Intelligence Agency Abuses and Failures

A cascade of revelations about what the U.S. government had been doing ― and covering up ― would only fuel the flames of conspiracy. The 1971 leak of the Pentagon Papers proved that every post-war president lied to the public about Vietnam. Then Richard Nixon resigned the presidency because he was a crook. And just months after that, investigative journalist Seymour Hersh revealed that the CIA was engaged in intelligence operations on U.S. soil against U.S. citizens.

Sen. Frank Church, a Democrat from Idaho, and Rep. Otis Pike, a Democrat from New York, launched investigations and President Gerald Ford appointed a commission to be led by Vice President Nelson Rockefeller in the mold of the Warren Commission.

Church and Pike played good cop-bad cop with the intelligence agencies. Unlike Church, Pike initially refused to reach an agreement with the Ford administration about how the committee would handle classified information. Where Church was eventually able to release a series of damning reports to the public, the Ford administration fought Pike tooth and nail.

This was where the first big fight over a report’s release happened. The intelligence agencies’ efforts would provide a template for their future suppression of potentially damaging information.

Church informed the CIA that he would not suppress revelations about its involvement in overseas assassinations, spurring the Ford administration to suppress Pike’s even more damning report. After rejecting a deal with Ford to obtain certain classified information, Pike ultimately gave in to receive some documents on loan by giving the president the final say over declassification. Ford took advantage of this deal to suppress the entire report when Pike submitted it.

It took two weeks before excerpts of the report leaked into the pages of the Village Voice. Pike’s report slammed the Ford administration for “foot-dragging, stone-walling, and careful deception.”

And that’s where the finger-pointing started. Ford blamed Pike. Pike said it was a CIA frame job. The reality was more mundane. Before Ford suppressed the report, someone in Congress gave it to CBS journalist Daniel Schorr. Schorr, in possession of a suddenly classified document, decided that he “could not be the one responsible for suppressing the report.”

The Church and Pike Committee Reports revealed an out-of-control U.S. intelligence establishment that spied on American citizens, conducted undisclosed LSD tests, subverted domestic political activity, plotted (or maybe succeeded) to assassinate foreign leaders and spent hundreds of millions of dollars directly and indirectly interfering in foreign democratic elections.

The select investigative committees effectively transformed into the permanent intelligence committees that exist today. The rules they worked out to obtain, review and declassify executive branch intelligence became the rules for the permanent committees. But the Washington establishment was finally able to swing public sentiment against further investigations after undercover CIA officer Richard Welch was killed overseas.

During Church’s 1980 re-election campaign, Republican Sen. Jim McClure, Church’s fellow Idaho senator, blamed Church and his report for Welch’s death ― although there was no connection between the two. Church lost by 4,000 votes. It turns out, some people didn’t really want to know.

From Iran-Contra to Monica Lewinsky

Love HuffPost? Become a founding member of HuffPost Plus today.

In 1983, Congress actually exercised its constitutional power to direct foreign policy by banning President Ronald Reagan’s administration from funding right-wing Nicaraguan counter-revolutionary militias ― the contras. Reagan shrugged his shoulders and ordered his national security adviser to keep the contras “together body and soul.” The president’s national security team did this by, first, raising money from Saudi Arabia and, second, using the profits of arms secretly sold to Iran in exchange for hostages.

The scheme leaked to a Lebanese newspaper in 1986. Reagan appointed a commission headed by former Republican senator John Tower and the Justice Department named Lawrence Walsh, a former federal judge and deputy attorney general, as independent counsel to investigate any lawbreaking.

There was no fight over the Tower Commission report, but Walsh led a practically unending investigation that outlived both the Reagan administration and the subsequent one-term presidency of Reagan’s vice president, George H.W. Bush. Walsh’s investigation unofficially ended after Bush lost re-election in 1992 and, on the advice of his attorney general William Barr (yes, the same one), pardoned the remaining Reagan-era officials Walsh sought to prosecute and those previously convicted.

Walsh submitted his report in August 1994 to a special three-judge panel, which allowed any of the implicated officials to block the release by asking for a Supreme Court review. Reagan, former attorney general Edwin Meese and former White House aide Oliver North all threatened, but ultimately declined, to challenge the report’s release.

Independent counsel Kenneth Starr’s report about President Bill Clinton’s extramarital relationship with White House intern Monica Lewinsky was publicly released — unredacted. It was, at one point in time, the most downloaded item on the World Wide Web. It was disclosed because the rules governing Starr’s investigation stated that he submit his findings to Congress. Some Democrats argued the White House should be given time to read the report so it could respond. But the House voted 363-63 to make the report public before the White House, or really anyone, could read it. And that’s how we know what the president did with whom and where and with what.

In the wake of Starr’s investigation and Clinton’s ensuing, unpopular impeachment, Congress decided not to renew the independent counsel statute when it came due in 1999. Instead, Clinton’s Justice Department crafted new regulations for the appointment of a special counsel that dictated attorney general review of any final report. That is why Mueller submitted his report to Barr. And that is why Barr wields so much power over the report’s disclosure.

The 28 Pages

Following al-Qaeda’s attacks on September 11, 2001, Congress created a commission to investigate the failure to prevent the attacks and also launched its own intelligence investigation. The Senate and House intelligence committees produced a 832-page joint report, but President George W. Bush ordered 28 pages of the report to be entirely redacted. Those pages concerned the potential role of Saudi Arabia or Saudi government officials in the attacks.

Americans were already suspicious of the Saudi role in the attack. Fifteen of the 19 hijackers were from Saudi Arabia. So was the man behind the attacks, Osama Bin Laden. And, when all flights were grounded in the U.S., the government allowed Saudi diplomats and other Saudi citizens to leave the country on private jets.

In 2003, Sen. Bob Graham (D-Fla.), who wrote the report as the committee’s chairman in 2002, pushed the committee to declassify the 28 fully redacted pages under the rules established after the Church and Pike investigations, but the committee declined.

Both Democrats and Republicans introduced resolutions in subsequent congressional sessions to force disclosure of the 28 pages. A lawsuit against Saudi Arabia brought by families of 9/11 victims, survivors of the attacks and insurance companies also sought disclosure. The public pressure led President Barack Obama to finally deliver a redacted version of the 28 pages to the congressional intelligence committees that was subsequently made public.

Graham continues to call on the government to release more records from the 9/11 Commission and FBI and CIA investigations that could shed more light on Saudi Arabia’s connection to the attacks.

George W. Bush’s Torture Policy

Following the 9/11 terrorist attacks, the Bush administration instituted a secret torture program to allegedly extract information from detainees. Detainees were psychologically destroyed, one lost an eye and a few of them were killed.

The Senate Intelligence Committee, led by Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.), launched an investigation in 2009 after reports that Jose Rodriguez, director of the CIA’s National Clandestine Service, had destroyed nearly 100 videotapes of detainees being tortured. The Department of Justice started its own investigation into whether anyone broke the law in administering the torture program or destroying evidence.

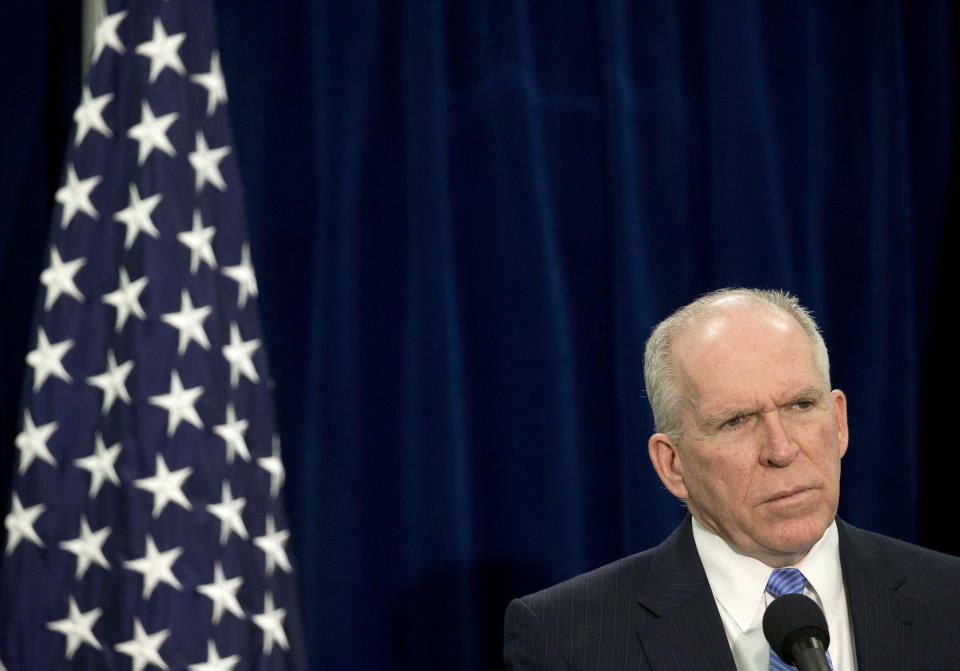

The committee completed its investigation in 2012, which set off a two-year battle with the CIA over its public release. The CIA did everything it could to prevent disclosure. It failed to meet the committee’s deadlines to approve the 6,000-page report for declassification. Recently confirmed CIA director John Brennan planned a full-scale campaign to oppose its release. The State Department sent a classified letter to the committee urging against declassification.

Brennan’s CIA put together a secret 122-page response criticizing the investigation and suggesting the entire report remain classified. But details of that response contradicted a prior review of the torture program conducted under previous CIA director Leon Panetta, as Senate aides pointed out. Aides copied the “Panetta Review” from the computers the CIA provided for their investigation as they feared that the CIA would delete the documents to cover up the discrepancy. These weren’t unwarranted fears. The CIA repeatedly deleted documents to hide them from Senate investigators.

Democrats then publicly revealed the existence of the Panetta Review. The CIA, in response, hacked Senate Intelligence Committee computers to find out if it has copies of the review. News of the hack soon became public and Feinstein took to the floor of the Senate to accuse the CIA of breaking the law. President Barack Obama refused to intervene.

By this point, Feinstein was resigned to the disclosure of an executive summary and not the disclosures of the full 6,000-page report. The committee voted to declassify a 522-page summary in April 2014, but continued its fight with the CIA over further redactions. Just like when the CIA objected to the Pike Committee revealing the agency’s ineptitude, the CIA wanted to save face by redacting the reports’ conclusions that the agency lied to Congress about its torture program. The summary was finally disclosed in December 2014.

But the fight didn’t end there. Brennan privately argued that the report should be completely destroyed so that it could never be publicly disclosed. A federal judge, however, ordered the report to be preserved in case it is needed in the prosecution or defense of the 9/11 conspirators.

Feinstein sent copies of the report to executive branch agencies, making it possible the report could be obtained by a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit. (Congress is not covered by the Freedom of Information Act.) The Trump administration, at the request of Senate Republicans, returned all copies of the report to the Senate Intelligence Committee in 2017, in order to block the report’s potential disclosure under a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit.

The fight for disclosure of the actual torture report continues.

The Mueller Report

Public disclosure of the Mueller report rests on the special counsel regulations crafted after Clinton’s impeachment and the lapsing of the independent counsel statute. These regulations provide a lot of leeway to the attorney general to redact, suppress or delay the report. Congressional Democrats have stated that they will not rest until they receive the full, unredacted report. This fight is likely to end up in the courts in contest over questions of executive privilege.

The court record on this question is mixed for Congress. But there is one trump card Nadler and the House Judiciary Committee could play. It is commonly ― although not universally ― believed that assertions of executive privilege must bend to congressional investigations into impeachable offenses.

What Nadler may need to do to get the full Mueller report is to declare the one thing Speaker Nancy Pelosi has said is off the table.

This article originally appeared on HuffPost.