I'm Trying To Reteach My Dad The Sport He Once Taught Me And It's Devastating

“Who’s that?” my dad says, gesturing to the TV screen in front of us.

I am startled to hear his voice.

“That’s Aaron Rodgers,” I say a little too enthusiastically, happy to engage with my father. “He’s the quarterback.”

A vacant stare from my dad.

“He throws the ball.”

Another stare from my dad, back to the place in his mind where he’s been for the last two years.

At 72, he’s in the late stages of Parkinson’s disease with dementia. It was misdiagnosed for almost three years, giving it too much time to progress unabated. He is finally getting proper treatment, but it doesn’t seem to be enough. I keep hoping for a medical miracle, for him to one day wake up as himself again.

I visit him in Wisconsin whenever I can. On this trip, I flew out from California on a red-eye. I couldn’t sleep during the four-hour flight even though I knew I should. I stared straight ahead in the dark cabin, feeling the sense of urgency that rises in me as my dad’s health declines: It’s the desire, the need, to tell anyone and everyone about him, how he’s sick, how he’s gone but not. About how he has ― had ― a great mind and was the kindest person most people have ever met.

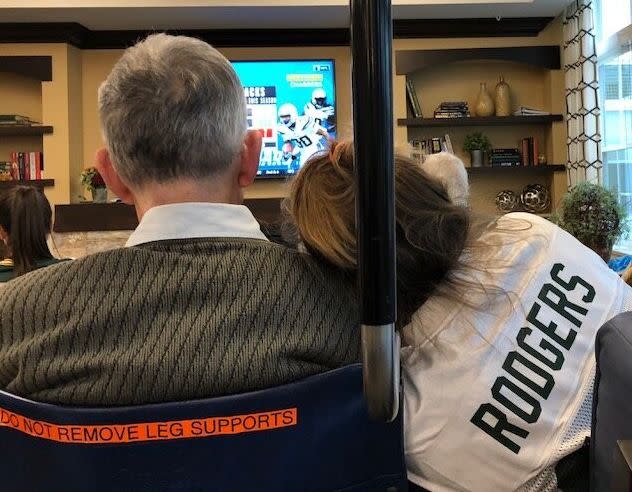

It’s a bleak, white sky November Sunday in Wisconsin. In the commons room of his assisted living center, as we watch TV, a red balloon floats down between our heads. It is “activity time” and, around us, other patients play tennis with badminton racquets and balloons. The room is carpeted and the chairs and pillows are thickly upholstered. This room, this whole place, was created for soft landings.

Administrators have deliberately put life around every corner: there are parakeets and cockatiels chirping in cages and turtles swimming in their tanks and therapy dogs roaming the halls. It sounds like we’re inside a pet store.

My mother was my father’s caretaker prior to this, but when he’d wander the house all night, miss steps on the stairs, get lost in and outside of their house, it became a necessity ― a matter of safety ― to move him into a facility with 24-hour care.

Now, he is so quiet.

My boisterous, once larger-than-life dad, the head and heart of our family, now looks like he’s been swallowed by his wheelchair. His clothes hang off of him; his cheeks are sallow. We lose a bit more of him daily. He can’t walk or feed himself anymore. He almost never speaks, unsure of himself. My mother tells me he isn’t quite sure what’s real and what isn’t.

We’re trying to watch our Green Bay Packers play football as balloons fall all around us now, like we’ve won big on a game show. I bat them away.

“We might make it to the playoffs, Dad,” I say. “Really strong team this year.”

He looks at me, as if just realizing I’m here.

I take his hand in mine.

“They got a first down,” I say, pointing at the television. He shakes his head, then shrugs.

I grab a subscription card from inside an AARP magazine sitting on a side table. On the back of it, I hastily draw a football field, with yard lines and end zones. This suddenly feels important, like if I can just get his understanding of football back, the rest of him could follow.

I can’t remember the first time my dad explained football to me, but it was undoubtedly at one of a handful of games we attended at Lambeau Field. Someone at my dad’s law firm gave him tickets on the 50-yard line for a few games during the Brett Favre era, and my dad took me, his young tomboy daughter. I’m sure he explained downs and turnovers and what constituted a penalty.

I don’t remember learning football; I feel like I’ve always known it. I remember the smell of beer and peanuts in the shell, and the below-zero temperatures that made us so cold in the stands that we prayed for numbness to finally set in. He would put his arm around me to keep me warm. We’d try to predict the next plays. “Watch,” my dad once said. “I bet Favre’ll run it in himself on 2nd and goal. Defense won’t expect it.” And so often, he was right. I associate roaring cheers of the crowd ― rippling like waves, bound by the mutual love we all shared for this team ― with my father.

As I grew up, I never missed a Packers game, even as I lived in different cities. When Green Bay played in the Super Bowl in 1997 against the New England Patriots, I was in college in Boston, Patriots country. While the majority of my classmates were at keggers, watching together, I was alone in my dorm room, wearing my Favre jersey, pacing in front of the television, on the phone watching it live with my dad in Wisconsin. He cried when they finally won.

For many seasons before he got sick, my dad would call me if a Green Bay player gained more than 40 yards on a single play. We’d relive it over long distance. “Did you see the way the kicker blocked for him? That’s teamwork at its best, Carrie!” he said. When Aaron Rodgers threw a 65-yard Hail Mary pass to his teammate in the end zone for a touchdown and walk-off win in Detroit a few years ago, I shook my own home’s family room in Los Angeles jumping up and down. Once I caught my breath, I called my dad.

Since he got sick, I’ve sometimes wondered if I love the sport itself or if I love it because it was a way to bond with my dad. I still never miss a game, but my team’s wins mean less when I can’t share them with him.

“Dad,” I say now, showing him the card as I draw hash marks on it. “Pretend these are yards—” I show my dad the football field I’ve drawn and try to reteach him what he once taught me. He nods, no doubt trying to understand for my sake.

I do love football. There are rules and people play by them, you can often predict what happens next. There’s a clock, and you know how much time is left. I know my father’s mind and memory won’t come back, never in the shape we once knew it. There is no recovery from his disease. I fold my tiny field in on itself and cap my pen, blinking back tears. I lift his arm and put it around my shoulder, lean into him, and watch our beloved team lose.

Carrie Friedman lives in Los Angeles. She has been published in the Washington Post, the Los Angeles Times, and Newsweek magazine, among others. You can find more from her at www.carriefriedman.com.

Do you have a compelling personal story you’d like to see published on HuffPost? Find out what we’re looking for here and send us a pitch!

More from HuffPost Personal...

My Two Sons Came Out As Gay And It Almost Destroyed Me. Here's What Saved Me.

I’m A Surgeon. Here’s What Happened When I Held My Patient’s Hand And Prayed For Her.

Trump Tweeted That He ‘Saved Pre-existing Conditions.’ Then Why Is My Daughter's Life On The Line?

Love HuffPost? Become a founding member of HuffPost Plus today.

This article originally appeared on HuffPost.