October Was Mexico's Deadliest Month On Record

October was the deadliest month in Mexico since the government first began recording homicides two decades ago, with a staggering 2,371 murder investigations opened nationwide last month.

An average of 69 people were killed each day in Mexico in 2017, Reuters reported Tuesday, as the country grapples with widespread drug trafficking, cartel violence and high-level corruption. Well over 20,000 people have been slain so far this year, government data reveals.

Just days ago, armed robbers shot and killed Adolfo Lagos Espinosa, the vice president of Mexican telecommunications giant Televisa, outside Mexico City. On Monday, human rights ombudsman Silvestre de la Toba Camacho and his 20-year-old son were assassinated in the state of Baja California Sur, according to Mexican authorities. Their deaths reflect a growing epidemic of violence in the country.

Journalists have also been increasingly targeted ― especially those covering organized crime and corruption. Earlier this year, crime reporter Miroslava Breach Velducea was fatally shot eight times in front of her children outside their home in the northern state of Chihuahua. The assailant reportedly left a note at the scene, which read: “For being a snitch.”

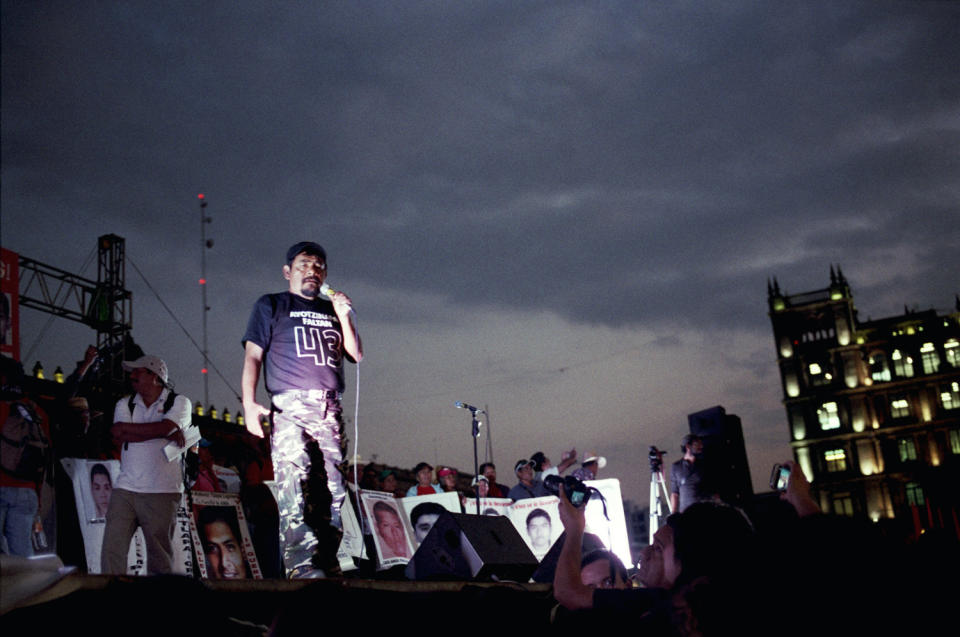

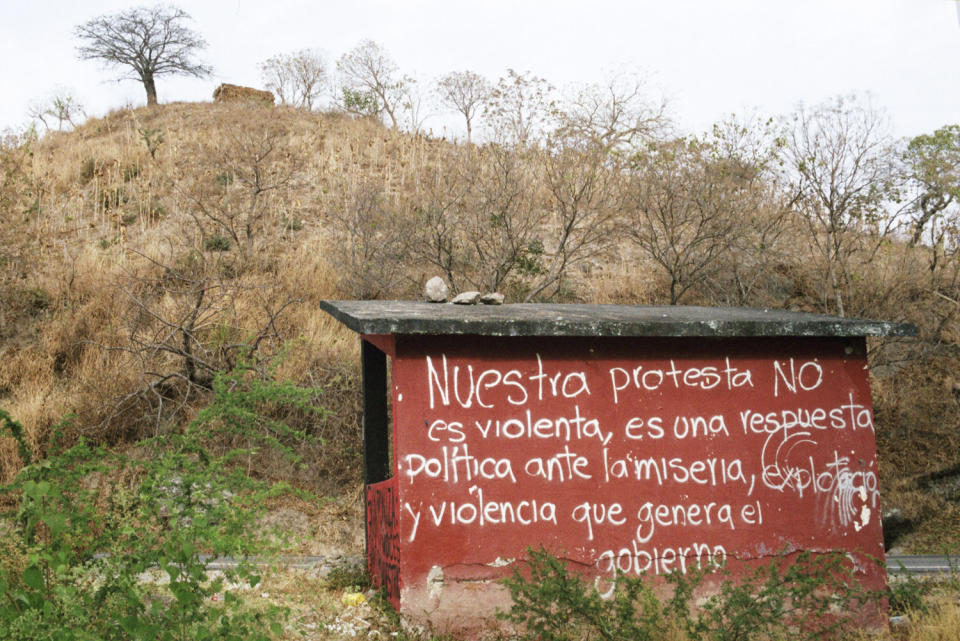

Repeated attacks on the press have bred fear and self-censorship, and in turn, a cycle of impunity. Many reporters have fled the country, stripping Mexico of critical voices demanding change and accountability.

A study published by the International Institute for Strategic Studies in May claimed Mexico’s drug war was the second-deadliest conflict in 2016, following the Syrian civil war. Although widely disputed, the report was tweeted out by U.S. President Donald Trump, whose administration is working to construct a multibillion-dollar wall along the U.S.-Mexico border to reduce illegal immigration and cross-border crime.

The Mexican government began a militarized crackdown on drug trafficking about a decade ago that has dramatically backfired, with lasting consequences. Some estimates suggest the death toll from the 10-year conflict exceeds 150,000.

The Mexican Senate’s internal research office reported that the country experienced “historic lows” in homicides near the end of 2006. But national homicide figures tripled between 2007 and 2011, as then-President Felipe Calderón mobilized tens of thousands of soldiers to eradicate drug-related crime. “It was after the start of the permanent [military] operations that a real epidemic of violence occurred at a national level,” according to the report.

The military intervention to quash drug cartel operations also triggered a surge in reported human rights abuses perpetrated by state officials. From 2006 to 2011, complaints against the National Defense Ministry filed with Mexico’s National Human Rights Commission shot up from 182 to 1,626. The government’s strategy bypassed regional authorities and institutions, leaving them vulnerable to criminal influence, the International Crisis Group said in a report earlier this year.

Enrique Peña Nieto, Mexico’s deeply unpopular president elected in 2012, vowed to move away from militarization as the primary strategy to address the crisis. But his administration has little to show for it, and has worked to expand the powers of Mexican troops despite mounting allegations of civilian abuse and extrajudicial killings by the armed forces.

Peña Nieto, whose Institutional Revolutionary Party faces a challenging bid for re-election in 2018, acknowledged in a speech earlier this month that confrontation between various armed groups has “really become an everyday scenario in many parts of the country.”

“Security must remain our top priority to our country,” the president said. On Thursday, he signed a law that dedicates more resources to investigating the increasing number of disappearances in Mexico.

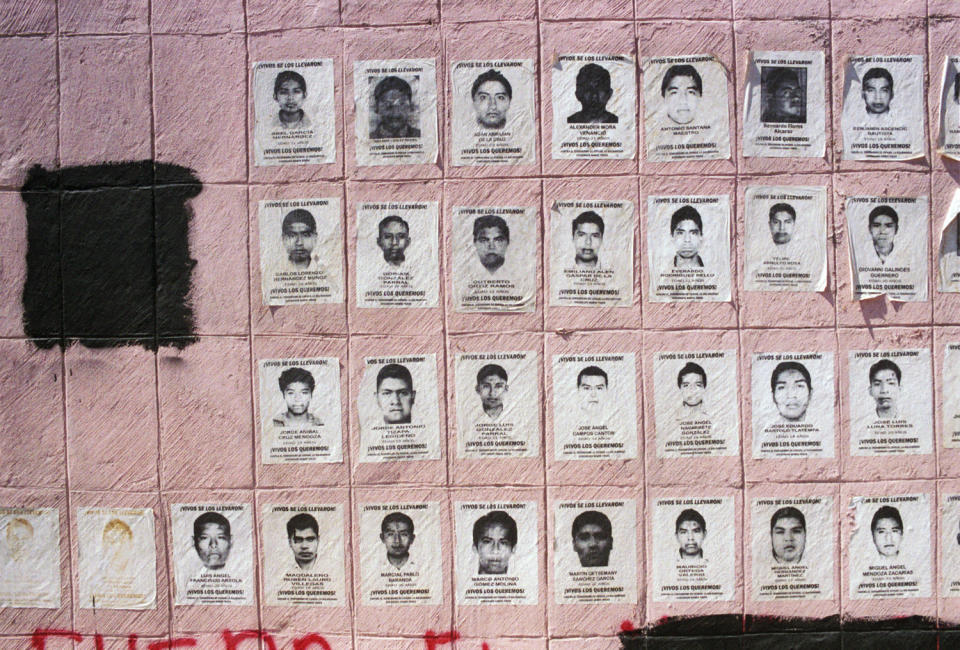

“The disappearance of people is one of the greatest challenges facing our human rights ... and one of the most painful experiences anyone can suffer,” he said. Over the past five decades, Reuters notes, more than 32,000 Mexicans have disappeared. More than half have gone missing during Peña Nieto’s six-year term.

Also on HuffPost

Love HuffPost? Become a founding member of HuffPost Plus today.

This article originally appeared on HuffPost.