Trump's Last, Desperate Attack On Obamacare Goes To The Supreme Court This Week

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Donald Trump has lost the presidential election, but his last, desperate effort to kill the Affordable Care Act will get its day before the U.S. Supreme Court on Tuesday, when the justices hear arguments in a Republican-backed lawsuit alleging that Obamacare is unconstitutional.

The case, known as California v. Texas, is the third such challenge to reach the high court since the law’s 2010 enactment. And the stakes are as high as ever. If the justices wipe out the Affordable Care Act, as 18 Republican state officials and the Trump administration have asked it to do, roughly 21 million Americans could lose health insurance, according to independent projections.

The law’s protections for people with preexisting conditions would no longer be in effect, less-visible reforms covering everything from billing fraud to food calorie postings would vanish, and the entire health care system could plunge into chaos.

The merits of the case are notoriously weak. Even conservative and libertarian lawyers who supported past challenges to Obamacare have filed friend-of-the-court briefs urging the justices to reject this one. For that reason, most legal observers think the chances of this lawsuit succeeding are small.

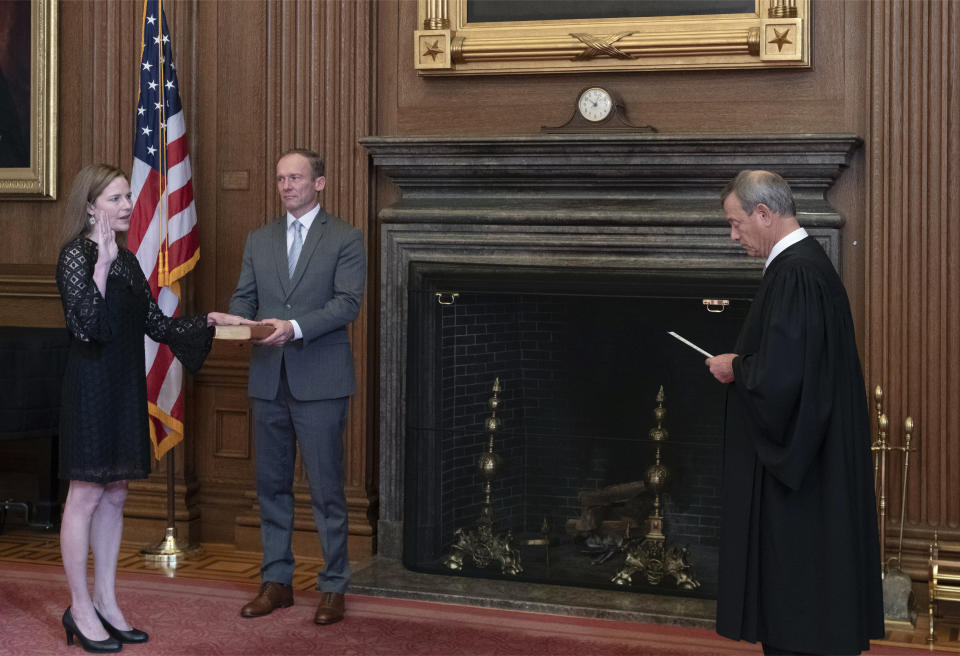

But a small chance is still a chance, especially given that this far-fetched lawsuit has gotten favorable rulings from three lower court judges. All three were Republican appointees, just like the Supreme Court majority, which now numbers six conservatives, with Amy Coney Barrett recently placed on the bench.

Tuesday’s oral arguments will offer the first hints of how she and the rest of the justices view this case, although an actual ruling will likely wait several months, maybe even until the spring.

Almost No Legal Expert Thinks The Case Has Merit

In theory, even the conservatives justices should make quick work of the case.

The basis for the lawsuit is the Affordable Care Act’s “individual mandate.” As originally written, the health care law imposed a financial penalty on people who could get insurance but did not.

The idea was to make sure healthy people enrolled before they got sick, so they would have protection against bills, so that they wouldn’t require charity care that would raise costs throughout the system, and so that insurers could keep premiums low and stable.

The mandate was always among the law’s most controversial features and was the basis for the first legal challenge, which suggested Congress lacked authority to impose such a requirement. The court rejected that lawsuit, with Chief Justice John Roberts leading a 5-4 majority, on the theory that the financial penalty was simply a tax and Congress has the power to impose taxes.

In 2017, Congress reduced the penalty to zero, as part of the Republican tax cut bill that Trump signed. Twenty Republican state officials then filed a new lawsuit, arguing that if the penalty was zero, the mandate ― whose language remains part of the statute ― can no longer be a tax.

That means the mandate is an unconstitutional command, and, the lawsuit says, the entire law has to come off the books because its parts are so interconnected.

The legal theory behind the lawsuit includes a series of arguments that scholars from across the political spectrum have criticized and, occasionally, mocked. How can there be a command to get insurance when the consequence for disobeying it is literally nothing? Do the people bringing the lawsuit even have standing to sue?

But the weakest argument, the one that has prompted so many of the law’s critics to dismiss it, is about a concept called “severability.” Under a well-established doctrine, judges ruling part of a law unconstitutional are supposed to do minimal damage to the rest of the law if they can.

The plaintiffs insist the entire statute has to come off the books because that is what Congress intended. But it was Congress, in 2017, that decided to zero out the mandate while fully aware that the rest of the Affordable Care Act would stay in place.

More recently, some COVID-19 relief measures have extended or built upon part of the Affordable Care Act ― which is yet more proof, as University of Connecticut professor John Cogan has argued, that Congress understood the law would stay in place and supports that.

One hint to how the Supreme Court might vote on this case comes from Justice Brett Kavanaugh, who in two recent rulings indicated he supports the traditional notion of severability. That might suggest he’s inclined to leave the rest of the Affordable Care Act in place, even if he buys the argument that the mandate has now become unconstitutional.

An answer Barrett gave at her confirmation hearing, when the issue of the Affordable Care Act came up repeatedly, suggests that she too has a traditional view on severability.

But there is no way to be sure, especially because her answer left some observers thinking she might agree with the plaintiffs on the rest of the argument.

And the consequences of a decision going in the other direction, wiping out the Affordable Care Act, would be enormous.

Millions Would Lose Insurance, Insurance Protections

The Affordable Care Act protects people with preexisting conditions, mostly by prohibiting insurers from denying them coverage or charging them higher premiums. It also requires that all plans cover 10 “essential benefits,” including mental health, maternity care and prescription drugs.

If the Supreme Court strikes down the law, those protections disappear. But such a ruling would do much more.

Today, Americans who buy insurance on their own can get tax credits if their income is below four times the poverty line (about $100,000 a year for a family of four). Those credits effectively discount premiums by hundreds and sometimes thousands of dollars a year. They would be gone if the Affordable Care Act comes off the books, leaving millions to buy coverage on their own without that assistance.

Some would still get insurance, and if they are young and healthy, they might even be able to get it more cheaply than they do now. But they would likely have less-comprehensive coverage with big gaps in benefits.

Many more Americans would lose Medicaid coverage because all but a dozen states have expanded eligibility to include everybody living below or just above the poverty line, providing coverage that’s federally funded. That federal funding comes from the Affordable Care Act, and it, too, would stop if the law is no longer in effect.

“States would have to quickly decide whether to continue covering some or all of these adults with their own funds,” according to Judy Solomon, a senior fellow at the left-leaning Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. “It’s doubtful many would be able to do that.”

In some states, cuts would happen automatically because the executive actions or laws authorizing expansion call for restoring the pre-expansion eligibility standards if the extra federal funds stop flowing.

Between the loss of tax credits and the end of Medicaid funding, 21 million people would lose insurance, according to estimates by the nonpartisan Urban Institute.

A Ruling Against the Law Would Unleash Chaos

Even that figure doesn’t capture the full extent of the consequences from a Supreme Court decision against the health care law.

The Affordable Care Act strengthened Medicaid by funding new home-based care options for the disabled and elderly. These initiatives would lose their authorization, leaving decisions about whether to continue the programs in the hands of cash-strapped state officials.

Sponsors of private employer plans, through which roughly half of all Americans get insurance, could once again impose annual or lifetime limits on benefits, since it’s the Affordable Care Act that made such limits illegal. That could really hammer patients with rare forms of cancer or congenital conditions, such as hemophilia, for which treatments can easily exceed $1 million per year or sometimes even per month.

Medicare recipients would also feel the effects. The Affordable Care Act bolstered it in several ways, most obviously by gradually eliminating a gap in prescription drug coverage that became known as the doughnut hole. Without the Affordable Care Act in place, that gap could open back up, leaving seniors to pay more money for their drugs.

It’s unclear how precisely that would work out because a law was enacted in 2018 to close the doughnut hole ahead of schedule. That legislation was a modification of the Affordable Care Act, and judges would have to sort out what that modification means if the ACA comes off the books.

And that’s just one example in which the courts would have to sort out modifications to the Affordable Care Act that Congress has passed since its inception.

“It’s almost impossible to wrap your brain around how this would actually work,” Sabrina Corlette, a research professor at Georgetown University, told HuffPost. “It’s almost like you’d need a special master to go through these changes, line by line, to figure out what’s constitutional and what’s not.”

Likewise, a number of pilot programs to reengineer Medicare payments for health care, in order to improve the program’s efficiency and promote better quality care, are now underway. The experiments are taking place through the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation, which the Affordable Care Act authorizes and finances.

Shutting down the law would mean shutting down the center and its programs, with unknown consequences for the health care providers participating in them.

“I don’t even know what I’d tell a health system if they came to me asking what to do,” said Nicholas Bagley, a professor of law at the University of Michigan.

And then there would be effects that have nothing to do with health insurance. The law is the reason that restaurant chains must post calorie counts on their menus, for example. It modified the Indian Health Service and changed the approval process for so-called biosimilar drugs.

One Sentence Could Make The Case Go Away

Health care policy is all about tradeoffs, so for all these changes, there would be countereffects, including a reduction in taxes on the wealthy that the Affordable Care Act raised to finance its coverage expansions.

But the “effects of invalidation of the ACA would be devastating to our entire health care system,” said Timothy Jost, a law professor emeritus at Washington and Lee.

“Medicare payment rules, fraud and abuse prohibitions, Indian Health Service reforms, the Medicaid expansion, FDA authority over generic biologics — all would fall by the wayside,” Jost said.

Congress could always render the lawsuit moot by approving a one-sentence law eliminating the language of the mandate, for example. So far, nobody has seriously tried to pass such a measure.

Unless that changes, the outcome will depend on the Supreme Court, where nothing is guaranteed.

Related...

How Trump Plotted To Kill Obamacare

If The ACA Is Struck Down, Millions Of Lives Will Be At Risk — Including Mine

How Joe Biden Navigated Pandemic Politics To Win The White House

Love HuffPost? Become a founding member of HuffPost Plus today.

This article originally appeared on HuffPost and has been updated.