New York City To Consider Bill To Budget Climate Emissions Like Finances

New York City could become the first big U.S. city to budget its climate-changing emissions like its finances, cribbing a model the Norwegian capital of Oslo pioneered three years ago.

The plan is laid out in a new bill set to be introduced Wednesday morning in the City Council.

HuffPost obtained a draft of the legislation, which proposes to amend the city’s administrative code to require the mayor’s office to set an emissions budget and allot a limited volume of greenhouse gases to each agency and city-funded nonprofit. The budgets would be evaluated at the end of every fiscal year.

“This raises the urgency at every level of government and makes clear what stakes we’re playing for,” Councilman Costa Constantinides, a Queens Democrat and the legislature’s top climate champion, said by phone. “If we don’t deal with the climate crisis, our communities won’t exist anymore.”

Buildings, wastewater treatment and vehicles make up the bulk of the New York City government’s emissions, which fell 29% in the decade after 2007, according to data from the mayor’s Office of Sustainability.

But as scientific projections for global warming grow more dire, particularly for sprawling coastal metropoles like New York, calls for new policies to cut emissions and adapt to a more violent environment are mounting. With the emergence of the Green New Deal, a framework for a radical industrial plan to eliminate most emissions over a decade, the climate movement is increasingly animating the Democratic Party, which controls much of New York City.

Last Friday, roughly 300,000 protesters flooded lower Manhattan for an international climate strike led by teen activist Greta Thunberg.

The climate budget bill, Constantinides said, would force city agencies to “think about these things on a yearly basis.”

“It’s not in the abstract,” he said. “Every single year they’re going to have to have these conversations. It’ll be a constant reminder of the need to protect our communities.”

In April, the city enacted the Climate Mobilization Act, which activists dubbed New York’s own version of a Green New Deal. The sweeping bill required landlords of buildings larger than 25,000 square feet to slash emissions 40% by 2030, and added new incentives to construct more rooftop solar and wind power systems.

The legislation, which Constantinides authored, was part of a wave of bills he hopes the council will pass over the next year. In June, he proposed a trio of bills to replace the infamous jail complex on Rikers Island with a solar farm and wastewater treatment plant. Another bill, introduced in February, proposes creating a whole new agency called the Department of Sustainability to spearhead the city’s decarbonization effort.

That proposal has stalled in the legislative process, but Constantinides said he was “working to make it happen.” The Department of Sustainability isn’t mentioned in the latest bill, but such an agency could play a key role in overseeing the climate budget.

Between 2016 and 2020, Oslo projects emissions to fall by 460,000 metric tons compared to 2015 levels as a result of policies the city passed under its 2017 budget, according to a European Union report. That’s in part due to the coordination of the Oslo Agency for Climate, a department established in 2016 under the same law that enacted the budgeting system.

The New York bill’s prospects are unclear. But Council Speaker Corey Johnson, a Democrat, was a major force behind the Climate Mobilization Act and is now exploring a run for mayor in 2021. Mayor Bill de Blasio touted ― and, at times, inflated ― his efforts to cut the city’s emissions during his failed run for the Democratic presidential nomination. Neither Johnson nor the mayor responded to requests for comment Tuesday afternoon.

One thing is certain: The bill is good politics for Constantinides. Last week, he announced his candidacy for Queens borough president. The Astoria, Queens, native envisions spending the typically sleepy bureaucratic office’s roughly $65 million budget on climate adaptation efforts across New York’s most diverse and geographically largest borough.

Related Coverage

Ambitious New York City Bill Aims To Replace Gas-Fired Power Plants With Renewables

In A First, New York City Bill Would Create A New Agency To Manage Climate Change

New York City Charges Ahead With Its Own Green New Deal

Also on HuffPost

Love HuffPost? Become a founding member of HuffPost Plus today.

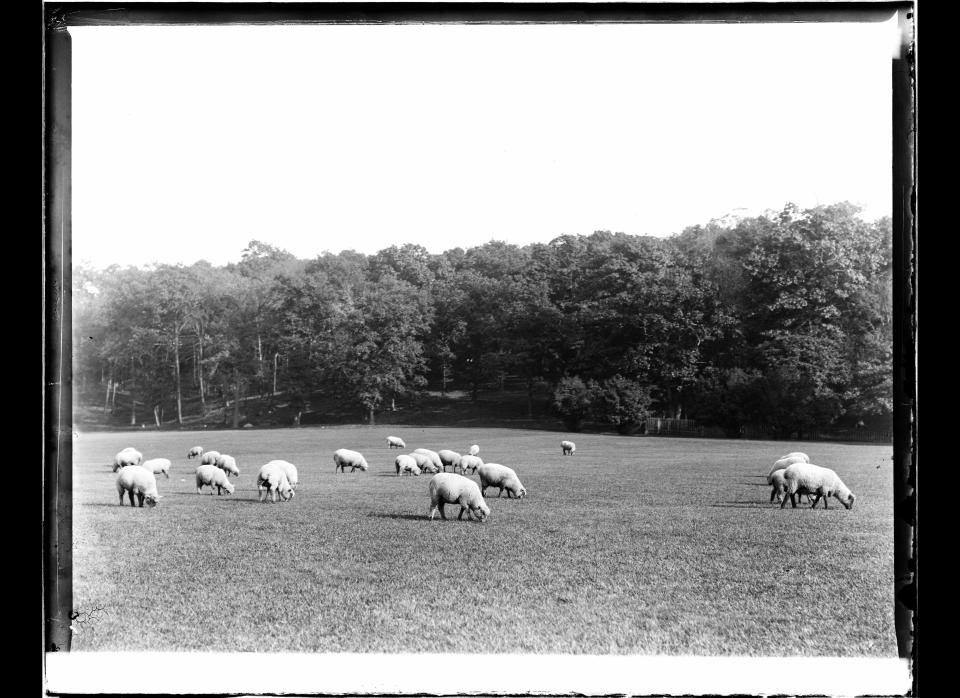

Prospect Park

Central Park

![<a href="http://collections.mcny.org/mcny/C.aspx?VP3=CMS3&VF=MNY_HomePage#/ViewBox_VPage&VBID=24UP1OLGRAW0&IT=ZoomImageTemplate01_VForm&IID=2F3XC5IWEI6U&LBID=24UPFQ5CFIR&PN=2&CT=Lightbox" target="_hplink">[Belvedere Castle, looking north], ca. 1880, Augustus Hepp, from the collections of the Museum of the City of New York. </a> Belvedere Castle was designed by Central Park’s architect, Calvert Vaux, to be an observation tower and a landmark visitors could use to orient themselves within the park. The castle was built out of Manhattan schist, meant to give the impression that the structure is rising out of the ground itself.](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/_YiRLUWeW4HQvq5ZZSPzXg--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MA--/https://img.huffingtonpost.com/asset/5be35e0e26000058018461ac.jpg)

Morningside Park

![<a href="http://collections.mcny.org/mcny/C.aspx?VP3=CMS3&VF=MNY_HomePage#/ViewBox_VPage&VBID=24UP1OLGRAW0&IT=ZoomImageTemplate01_VForm&IID=2F3XC5IARUET&PN=12&CT=Lightbox" target="_hplink">[116th Street stairs in Morningside Park], 1889, photographer unknown, from the collections of the Museum of the City of New York. </a> Prior to becoming Morningside Park, the vicinity had many names. Native Americans called it Muscoota and the Dutch called it Vredendal, or Peaceful Dale. Later it was called Vandewater Heights after its landowner. The area was designated park land in 1870 after it became obvious that it would be difficult to extend the city’s grid over the schist outcroppings.](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/KFBTWa5ZMiAfujUog22V8A--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MA--/https://img.huffingtonpost.com/asset/5be35e103c00008e030e9f11.jpg)

Fort Greene Park

![<a href="http://collections.mcny.org/mcny/C.aspx?VP3=CMS3&VF=MNY_HomePage#/ViewBox_VPage&VBID=24UP1OLGRAW0&IT=ZoomImageTemplate01_VForm&IID=2F3XC5IKVWA1&PN=4&CT=Lightbox" target="_hplink">[Fort Greene Park], ca. 1900, photographer unknown, from the collections of the Museum of the City of New York. </a> Fort Greene Park was the site of Fort Putnam, constructed in 1776, and surrendered to the British in the Battle of Long Island. Walt Whitman, in his auspices as the editor of the Brooklyn Eagle, championed turning the land into a park in 1845. Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, architects of both Central and Prospect Parks, designed the steps and parade grounds shown here, as well as the crypt that houses the remains of more than 11,500 patriots who died on prison ships off the shore of Brooklyn in the Revolutionary War.](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/zR5YDF_E5eqAIwC9aQlcFg--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MA--/https://img.huffingtonpost.com/asset/5be35e122000007505027917.jpg)

Dewitt Clinton Park

Washington Square

![<a href="http://collections.mcny.org/mcny/C.aspx?VP3=CMS3&VF=MNY_HomePage#/ViewBox_VPage&VBID=24UP1OLGRAW0&IT=ZoomImageTemplate01_VForm&IID=2F3XC5IXMULB&PN=15&CT=Lightbox" target="_hplink">[Washington Square Arch at night], 1909, photographer unknown, from the collections of the Museum of the City of New York. </a> Though Washington Square Park sometimes functions as an extension of the New York University campus, it is, in fact, a city park. Like Bryant Park and Union Square, Washington Square Park was also a potter’s field: more than 20,000 bodies are buried there. The original Washington Arch was a plaster and wood edifice constructed to commemorate the centennial of George Washington’s inauguration. A permanent, marble version, designed by Stanford White, was erected in 1892.](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/hDTVhGx5l5BrKrAu3NaX8w--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MA--/https://img.huffingtonpost.com/asset/5be35e153c0000a2020e9f13.jpg)

Bowling Green

![<a href="http://collections.mcny.org/MCNY/C.aspx?VP3=CMS3&VF=MNY_HomePage#/ViewBox_VPage&VBID=24UP1OLGMIXT&IT=ZoomImageTemplate01_VForm&IID=2F3XC5UXG6W2&PN=7&CT=Lightbox" target="_hplink">[Broadway, Bowling Green], ca. 1910, photographer unknown, from the collections of the Museum of the City of New York.</a> Believed to be the site of Peter Minuit’s purchase of Manhattan from Native American tribes in 1626, Bowling Green is the city’s oldest park. It is the terminus of Broadway, then called Heere Staat or High Street, a roadway that follows an ancient trade route north into the Bronx.](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/puY1PtuXaVQ04Amc3xypqA--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MA--/https://img.huffingtonpost.com/asset/5be35e18210000e304ca0cb6.jpg)

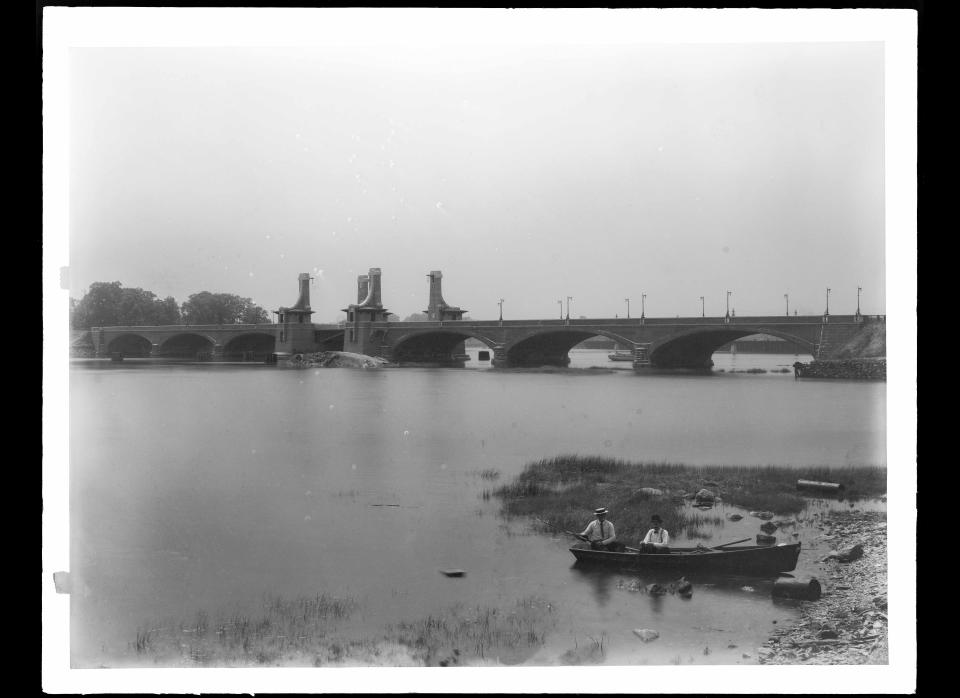

Pelham Bay Park

Battery Park

![<a href="http://collections.mcny.org/MCNY/C.aspx?VP3=CMS3&VF=MNY_HomePage#/ViewBox_VPage&VBID=24UP1OLGMVNJ&IT=ZoomImageTemplate01_VForm&IID=2F3XC58FUAIL&LBID=24UPFQ5CFIR&PN=6&CT=Lightbox" target="_hplink">[The Battery], ca. 1917, William Davis Hassler, from the collections of the Museum of the City of New York. </a> Battery Park is the seat of New York City history. The site was valued by the Native Americans for its strategic position and was the location of the first Dutch settlement in 1625. The land that became the park was expanded by landfill in the late 18th century and again in the mid-19th century. Castle Clinton (originally called the West Battery) was built in 1811 and hosted many civic and social events before becoming the hub for immigration on the east coast, preceding Ellis Island as the entry point for around eight million immigrants between 1855 and 1890.](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/fYajt1yahWGq7nOILomu5g--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MA--/https://img.huffingtonpost.com/asset/5be35e1c1f0000f504261cf3.jpg)

Carl Schurz Park

Sara Delano Roosevelt Park

Marcus Garvey Park

![<a href="http://collections.mcny.org/mcny/C.aspx?VP3=CMS3&VF=MNY_HomePage#/ViewBox_VPage&VBID=24UP1OLGRAW0&IT=ZoomImageTemplate01_VForm&IID=2F3XC5IW0UC7&PN=11&CT=Lightbox" target="_hplink">[Mount Morris Park], ca. 1935, photographer unknown, from the collection of the Museum of the City of New York.</a> Marcus Garvey Park was originally called Snake Hill by the Dutch because of its many resident snakes. It opened as Mount Morris Park in 1840 and was renamed in 1973 for the Jamaican-born Garvey, an advocate of Black Nationalism. The structure pictured here is a fire tower built in 1856.](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/oFu5XUGPcIqQ7tZcLcO32g--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MA--/https://img.huffingtonpost.com/asset/5be35e211d00002c0031183f.jpg)

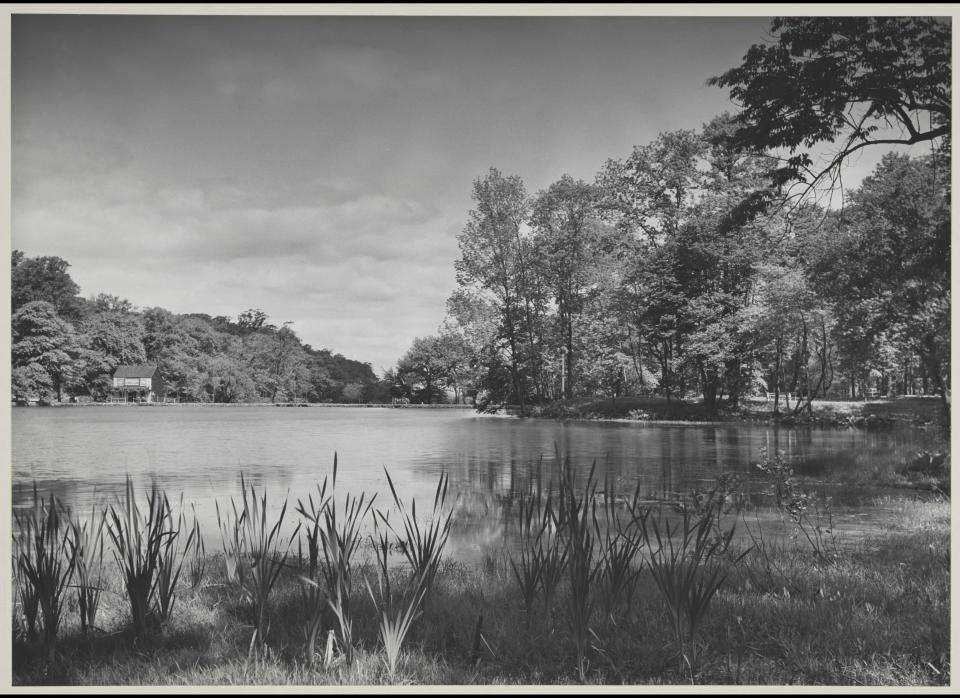

Alley Pond Park

Bryant Park

Union Square

This article originally appeared on HuffPost.