92-Year-Old Who Hid Jewish Family During Holocaust Meets Survivors' Grandchildren

A 92-year-old Greek woman was reunited in Jerusalem with members of the Jewish family she helped save during the Holocaust, in what organizers said could be the very last meeting of its kind.

More than 75 years ago, Melpomeni Dina and her two older sisters risked their own safety to offer shelter to the Mordechai family, a Jewish family of seven from Veria, Greece. The Mordechais lived in Dina’s home until their location was compromised and they were forced to find refuge elsewhere.

The Jewish family resettled in Israel after the end of World War II. The two surviving siblings brought their children and grandchildren to meet Dina on Sunday for the first time ― about 40 members in total, according to The Jerusalem Post.

Sarah Yanai, the oldest child in the family, reflected on the enormous risk Dina took as a teenager.

“We are now a very large and happy family and it is all thanks to them saving us,” Yanai, now 86, told The Associated Press.

Reunion ceremonies between Holocaust survivors and their non-Jewish rescuers have become increasingly rare as the generation that lived through World War II ages. Stanlee Stahl, executive vice president of the Jewish Foundation for the Righteous, told The Jerusalem Post that the organization has been holding reunion ceremonies between survivors and rescuers once a year since 1992. But many have died or are too frail to travel, and Stahl said she thinks the meeting between Dina and the Mordechais will be the last such reunion ever to take place.

“To me it is very, very, very special,” she told the AP. “In a way, a door closes, one opens. The door is closing ever so slowly on the reunions.”

Israel’s Yad Vashem Holocaust memorial recognized Dina, whose maiden name was Gianopoulou, as one of the “Righteous Among the Nations” in 1994. The title has been awarded to more than 27,000 non-Jews who risked their lives to save Jewish people during the Holocaust.

Mentes Mordechai and Miriam Mari, Yanai’s parents, were business owners in Veria, a city in northern Greece, at the start of World War II, according to Yad Vashem. Mari ran a fashion store and gave sewing courses to women in the area. One of those students was Efthimia Gianopoulou, Dina’s older sister. Because Gianopoulou was poor and an orphan, Mari did not charge her for the sewing lessons.

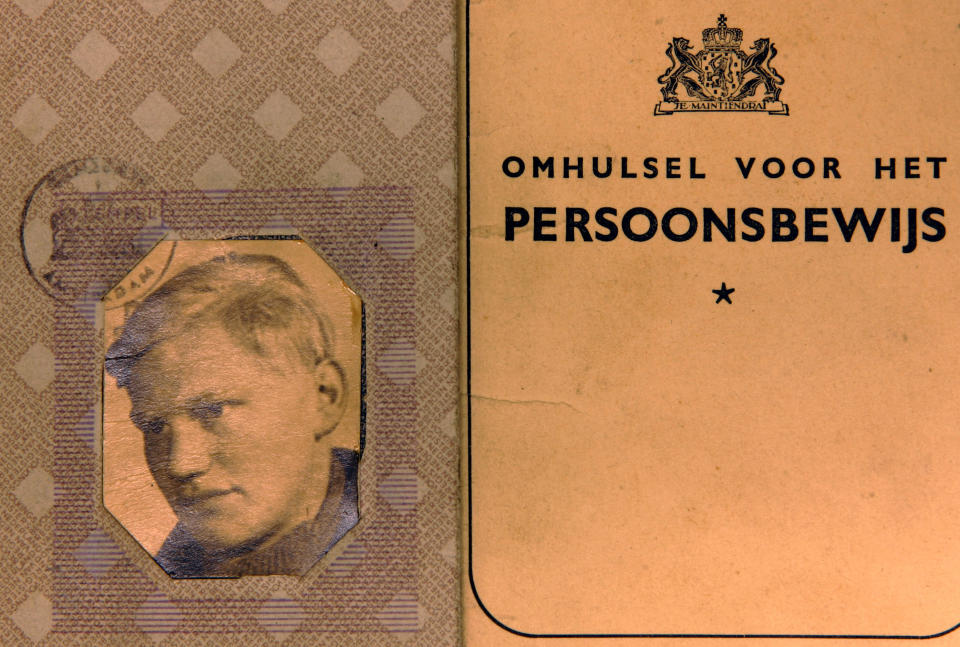

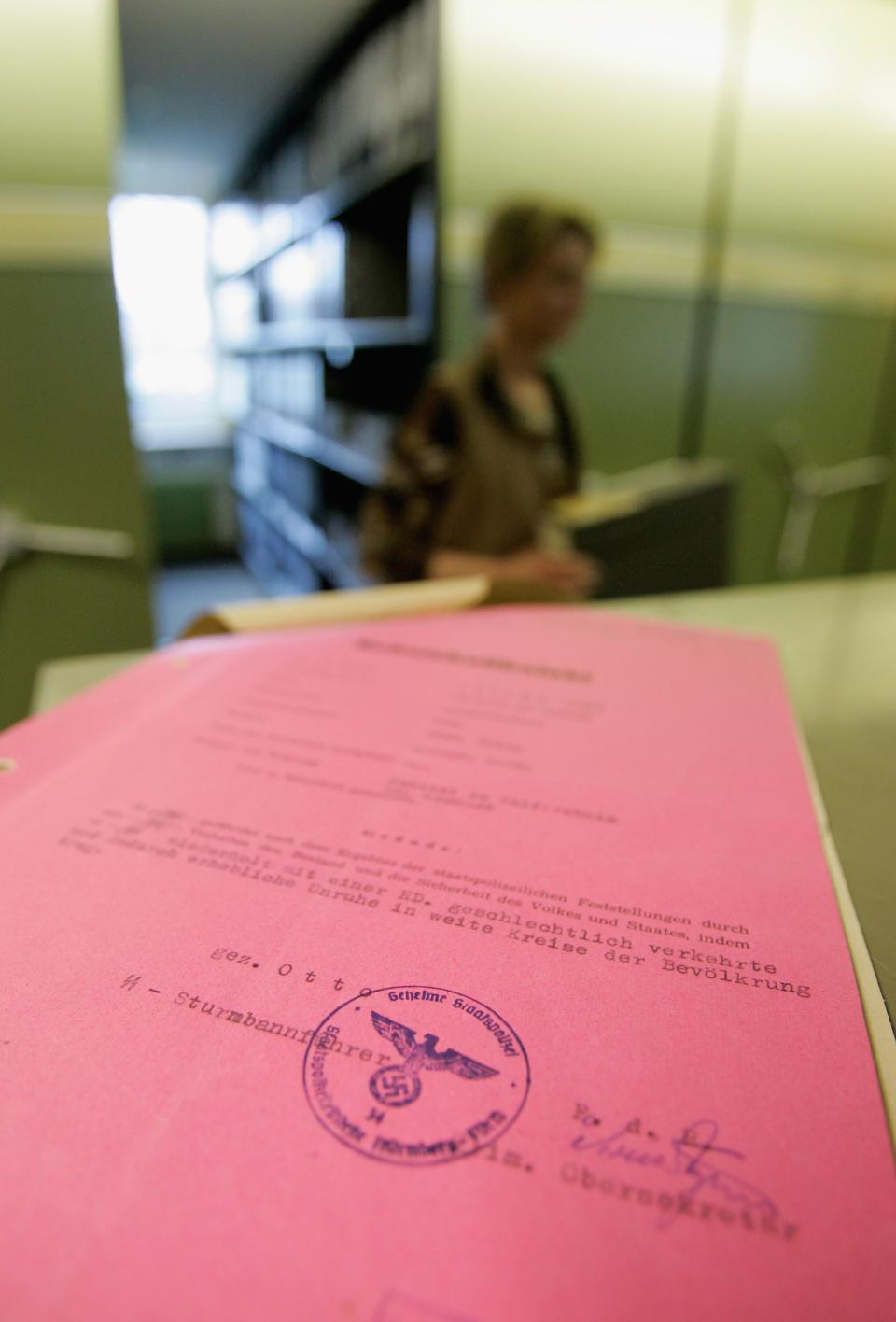

Life for the Mordechai family changed drastically after Greece surrendered to the Axis powers in 1941 and the Nazis’ persecution of Greek Jews began. The Mordechai family went into hiding in March 1943, after hearing of arrests and deportation of Jews in nearby Thessaloniki. Friends obtained false identification cards for the family and built a wooden ceiling into the attic of an abandoned Turkish mosque. The Mordechais lived there for about a year, but the space was cramped and poorly ventilated, and the family began to develop health problems.

That’s when Efthimia Gianopoulou stepped in, offering to let the family live with her and her two younger sisters in a single-room home on the outskirts of the city. The three sisters, who were all teenagers at the time, shared their food rations with the Mordechai family, supplementing the meager food supply by farming a piece of land they owned nearby. The middle sister, Bithleem Gianopoulou, would reportedly return from working the farm carrying a sack of food for 10 people on her back.

Then, one of the Jewish siblings, a 6-year-old named Shmuel, became gravely ill. He was taken to a hospital, where he died. Soon after, someone reported the Mordechai family to the authorities. Efthimia Gianopoulou’s relatives helped coordinate the Mordechai family’s escape to the nearby Vermio mountains, and the teenage sisters gave the family clothes to help them survive in the wild. The Mordechai family stayed there until the war ended, then moved to Israel.

Nazi Germany’s occupation of Greece ended in 1944. Up to 70,000 Greek Jews died during the Holocaust ― about 81% of the country’s Jewish population, according to the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Yanai and her younger brother, Yossi Mor, had met Dina in Greece years ago, the AP reports. But this was Dina’s first time meeting their children and grandchildren.

Mor, who was only about 1 year old when his family went into hiding, said he now has a “large and beautiful” family because of Dina.

“They were a very poor family,” the 77-year-old told The Jerusalem Post of the Gianopoulou family. “They saved us because they loved my mother for her good heart.”

Dina told reporters at the ceremony that the experience of seeing the Mordechai family’s descendants was deeply moving. She said that her and her sisters’ actions during the war “were the right thing to do.”

She told the AP that she can now “die quietly.”

Love HuffPost? Become a founding member of HuffPost Plus today.

Also on HuffPost

This article originally appeared on HuffPost.