Bad News For Biden: Nobody Has Won The Nomination After A Start Like This

The Iowa caucuses and New Hampshire primary have produced plenty of surprises over the years. Favorites have faltered and previously overlooked presidential candidates pulled off stunning victories; the hastily anointed front-runner who won in Iowa has tanked a week later in the Granite State. But one constant has held true since 1972: Nobody has ever finished outside the top two in both of the first two states and gone on to become the Democratic (or Republican) nominee.

That’s very bad news for former Vice President Joe Biden, who entered the contests as conventional wisdom’s front-runner and surely hoped to compete well in, if not win, both races. And it’s obviously good news for Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) and former South Bend, Indiana, Mayor Pete Buttigieg, who were the top two finishers in both states.

Losing produces negative momentum, which hinders fundraising, which means the losing candidates can’t compete effectively in later primaries. Winning, unsurprisingly, can do the opposite. Surprise second-place finishes in the early contests have also boosted candidates to either the nomination or at least a long-enough run to reach the party convention. No one has been boosted by a surprise third-place finish, let alone a humiliating fifth-place collapse.

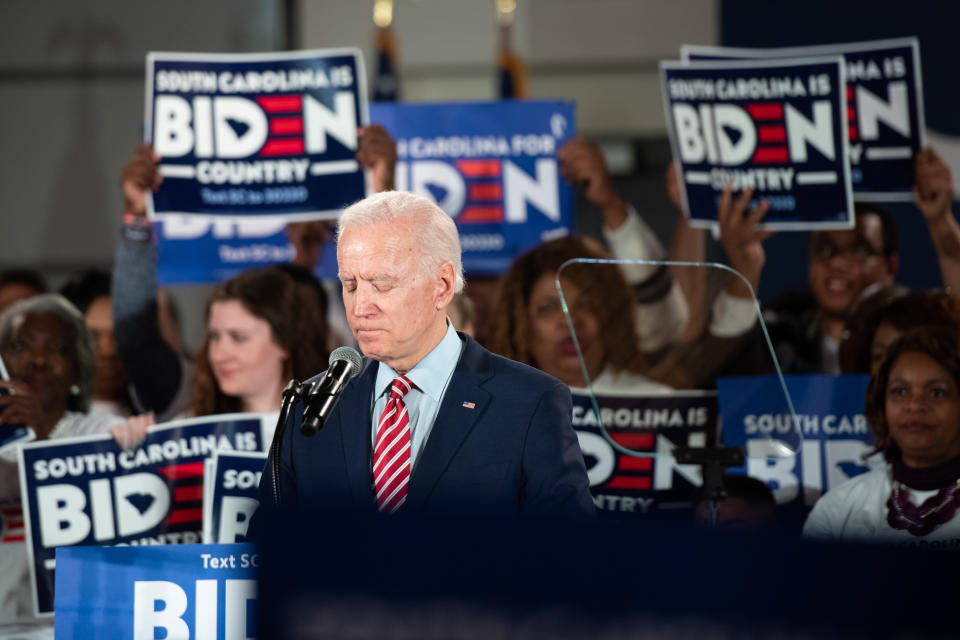

Biden will make a last stand in South Carolina, the first state where the majority of Democratic primary voters will be African American. He hopes to hold on to the strong support among older Black voters that he has shown in polls so far. But if precedent holds, South Carolina won’t be able to save him.

‘The Comeback Kid’

Prior to 1972, presidential nominations were decided at party conventions with the primaries and caucuses playing a limited role. Still, the New Hampshire primary results could be influential in the Democratic nominating process. Presidents Harry Truman in 1952 and Lyndon Johnson in 1968 both declined to run for reelection after receiving weak support in the New Hampshire primary. (The Iowa caucuses were of no importance until 1972.)

After the debacle of the 1968 Democratic National Convention, both major parties adopted reforms putting the real power of choosing a presidential nominee into the hands of state primaries and caucuses. Iowa and New Hampshire were placed at the start of the Democratic Party’s primary calendar.

Four years later, Sen. George McGovern (D-S.D.) used his surprising second-place finishes in Iowa and New Hampshire to build momentum towards the party’s nomination. Former Georgia Gov. Jimmy Carter, then little known outside his own state, used a victory in the Iowa caucuses to propel himself toward the nomination in 1976.

But the best-known instance of a candidate using a surprise second-place finish to win the nomination is President Bill Clinton’s “Comeback Kid” performance in the 1992 New Hampshire primary. The Granite State’s primary was effectively the first contest that year after a crowded field of Democratic candidates ceded the Iowa caucuses to Iowa Sen. Tom Harkin.

Clinton, then the governor of Arkansas, was beset by scandal heading into the New Hampshire primary while Sen. Paul Tsongas, from neighboring Massachusetts, was viewed as the prohibitive front-runner. The week before the contest Gennifer Flowers accused Clinton of having an affair with her and Clinton’s former ROTC officer accused him of manipulating his way out of the Vietnam War draft.

The campaign’s internal polling put him in the single digits. This left Clinton fighting for second place with Nebraska Sen. Bob Kerrey, a veteran who lost part of his right leg in Vietnam. And everyone knew that second-place finish mattered a lot.

“I knew you were not likely to survive as a presidential candidate if you’re third or fourth place coming out of New Hampshire,” Kerrey told The New York Times in a 2016 interview.

Clinton’s campaign staff, however, believed that his particular knack for retail politics would play well with New Hampshire voters. So he went wherever he could to shake hands and tell voters that he was going to fight for their interests. The goal was to finish second and come within less than 10 percentage points of Tsongas.

It worked. Clinton finished 9 points back of Tsongas, who won only 33%. New Hampshire had made him “the Comeback Kid,” Clinton declared in a victory speech.

Since 1972, only two other candidates have won their party’s nomination after not reaching the top two in Iowa: George H.W. Bush in 1988 and John McCain in 2008.

McCain skipped the Iowa caucuses in 2008 and finished fourth. As it did for Clinton, the New Hampshire primary saved him. He won there and then rolled to the nomination afterward. It marked a huge comeback for a candidacy that had nearly gone bankrupt one year earlier.

Why Could This Election Be Different From All Other Elections?

Precedents are, of course, made to be broken. And the momentum could fade for the top two Democratic finishers in this year’s first two contests.

One reason why the influence of the Iowa and New Hampshire contests could suffer in 2020 is the contrast between the diversity of the national Democratic Party base and the lack of diversity in those two states.

Iowa and New Hampshire are over 90% white. The Democratic Party is not. This tension has long been highlighted in efforts to dislodge Iowa and New Hampshire from their position as prime decision-makers in the party’s nomination calendar.

“Iowa and New Hampshire are wonderful states with wonderful people,” now-former presidential candidate Julián Castro said in November. “But they’re also not reflective of the diversity of our country, and certainly not reflective of the diversity of the Democratic Party.”

The third and fourth nominating contests in Nevada and South Carolina, respectively, do feature the kind of diverse electorate that represents the Democratic base. Biden has argued this is why his poor finishes in Iowa and New Hampshire should be discounted.

“Nothing’s going to happen until we get down to a place and around the country where there’s much more diversity,” Biden said on Sunday, after his fourth-place fall in Iowa and before his fifth-place disaster in New Hampshire.

But voters in the next two contests may change their minds based on the successful narratives of the top two finishers in Iowa and New Hampshire. Sanders and Buttigieg are garnering greater media attention noting that they are at the top of the contest. Winning creates positive press, which helps alter voters’ preferences.

That’s at least one reason why a 2010 study titled “Momentum and Learning in Presidential Primaries” found that Iowa and New Hampshire have five times more influence on who wins a party’s nomination than the larger, more diverse states that vote on Super Tuesday.

Another factor that might break the precedent this year is the unprecedented campaigns of former New York City Michael Bloomberg and, to a lesser extent, hedge fund billionaire Tom Steyer.

Bloomberg, who is worth more than $60 billion, has already spent more of his own money ― $310 million ― to win the Democratic nomination than any campaign has ever spent during a presidential primary season.

The strategy behind Bloomberg’s campaign is to skip the first four states and focus on the large Super Tuesday states where the ability to fund expensive television ads can drive voter behavior more than retail politics. No candidate can match him dollar for dollar. There is no way to judge what his torrent of cash will do.

Also on HuffPost

Love HuffPost? Become a founding member of HuffPost Plus today.

This article originally appeared on HuffPost.