New Jersey's Liberal New Governor Is The Anti-Chris Christie

TRENTON, N.J. ― New Jersey politics is a lot of things, but one thing it’s not is boring. There are the brusque, larger-than-life personalities; the shady real estate developers; the Godzilla vs. Megalon-level slugfests between entrenched interest groups; the random agencies whose existence you only learned about after indictments were unsealed (we’re looking at you, Passaic Valley Sewerage Commission); more shady real estate developers; and enough windbreaker-clad federal agents hauling boxes out of offices in cheerless strip malls to fill MetLife Stadium.

And for most of the past decade, there’s been Gov. Chris Christie (R), whose two terms in office ended Jan. 16: he of the combative town hall meetings, the burn-it-all-down political agenda and the vexing vehicular congestion in Fort Lee.

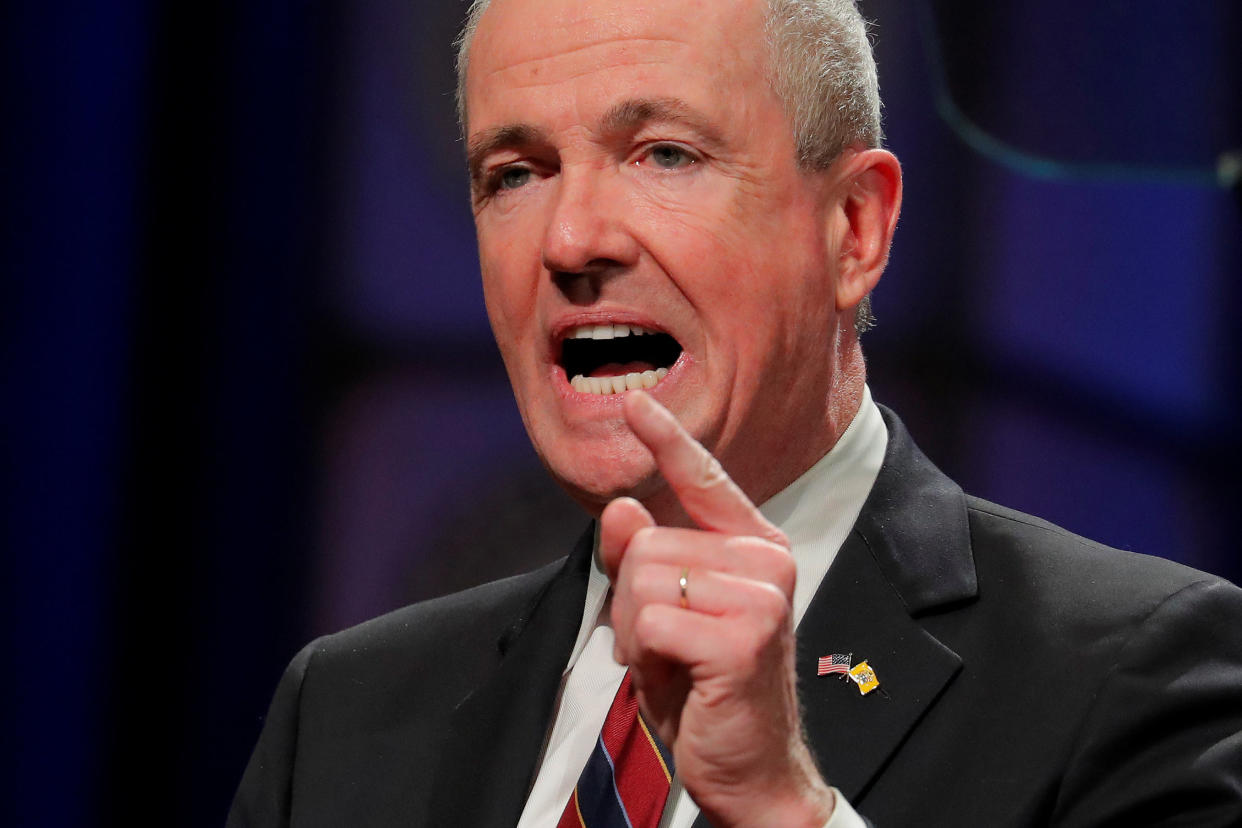

Into this goat rodeo comes Christie’s successor, Gov. Phil Murphy (D), who is rather boring. This isn’t a knock against the guy. He’s also likable, accomplished and in command of the issues — all fine qualities in a state executive. He has a difficult time relaxing his face into anything other than a 10,000-watt smile and speaks with a deep and inviting New England brogue, the result of his Boston childhood.

As center-left resumes go, Murphy’s reads like a Brookings Institution dream: 23 years at Goldman Sachs, a stint as finance chair of the Democratic National Committee under then party chief Howard Dean, ambassador to Germany under President Barack Obama, and founder of several progressive groups in New Jersey that set him up to run for governor.

And, perhaps most boringly, Murphy doesn’t yell at people during public appearances. Instead, he makes bland comments about the burdens endured by New Jersey taxpayers. Murphy doesn’t scowl or stare anyone down when he isn’t speaking. Instead, he assumes the international position of attentive politician: hands folded demurely over the crotch while solemnly nodding.

This is all very dull. Put another way, “Agreeable, wealthy Irish guy with magnetic smile and deep ties to Democratic party machine finds success in Northeastern politics” hasn’t exactly been a remarkable headline these last 100 years.

Yet excitement over Murphy has reached such levels that an outsider would be forgiven for assuming that somewhere on the Jersey Turnpike, a chauffeured black Suburban was ferrying Gov. Bruce Springsteen to a ribbon cutting at a women’s health clinic. National Democratic officials and observers are already speculating about Murphy and a possible run for national office.

One reason for all this excitement: Murphy’s relentlessly progressive agenda, realized in his first weeks in office through a slew of executive orders, including ones mandating equal pay policies in state agencies, prioritizing the development of wind energy, and establishing a commission to aid hurricane recovery efforts in Puerto Rico (a nod to the large number of state residents with island ties). On Feb. 21, he signed his first bill into law, restoring $7.5 million in funding for Planned Parenthood and other health care providers that had been deep-sixed by the Christie administration. Shortly thereafter, he signed another bill extending contraception access to Medicaid recipients.

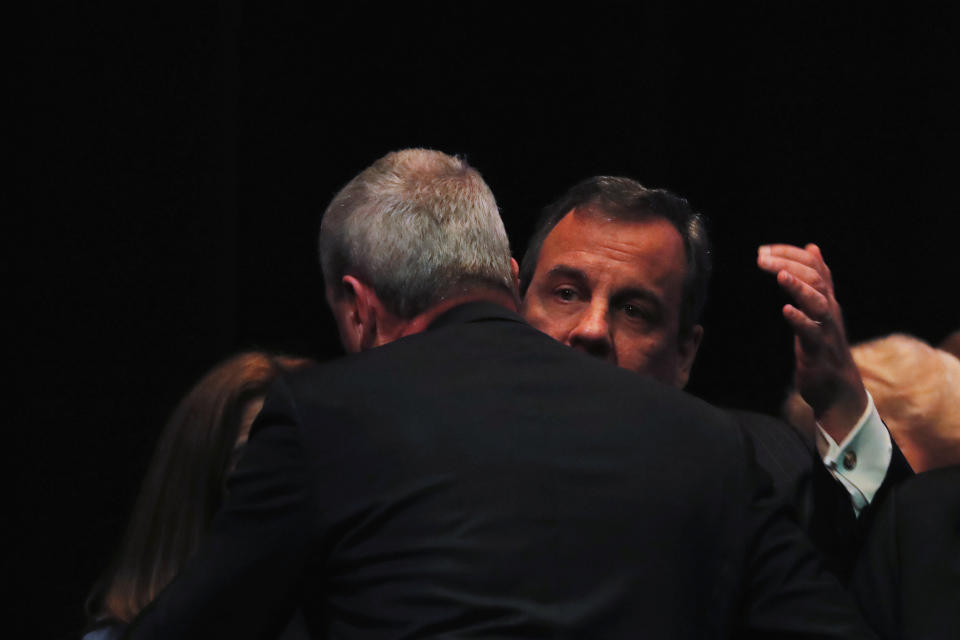

Another source of all the goodwill directed at Murphy: the near-palpable relief among many of the state’s liberal and moderate power brokers that he’s nothing like Christie.

“It was a welcome change and experience,” said Marie Blistan, president of the powerful New Jersey Education Association and a member of Murphy’s transition team, speaking of her interactions with the new governor. “His platform is the same now as it was when he was running for office.”

Tom Bracken, president and CEO of the New Jersey Chamber of Commerce, said he’s pleased to see a New Jersey governor focusing on the state. Asked if he would care to explain his thoughts on the previous administration, Bracken, whose organization often aligns with Republicans, diplomatically declined, saying with a chuckle that Murphy’s actions have been “very well received.”

Christie-bashing is a very rich vein to tap in Trenton (he departed the state capital with the lowest approval ratings of any governor in the nation). It’s appropriate, then, that Christie is one of the few topics Murphy actually gets emotive about.

“Our soul has sort of been ripped out of us the last few years,” he told HuffPost. “We’re digging out from eight years of a really difficult reality in the state.”

Many New Jerseyans are just glad to have a state executive who is not (at least not yet) plotting a run for president.

“The biggest change I’ve seen is we finally have a governor who is more interested in sound policy decisions than getting good quotes published in the press,” said Ed Potosnak, executive director of the New Jersey League of Conservation Voters.

A state-level focus will serve Murphy well in the coming weeks and months as he and New Jersey’s solidly Democratic legislature hammer out a budget and work on his top priorities, which include legalizing marijuana, raising the minimum wage and adapting the state’s tax code to the overhaul of the U.S. tax code signed by President Donald Trump last year ― legislation that increases the burdens on residents of progressive states like New Jersey with higher local tax rates.

But this is still Jersey politics, where being frenemies is the platonic ideal of a working relationship.

Murphy’s run for governor thwarted the gubernatorial ambitions of state Senate President Stephen Sweeney (D). Murphy’s money and Sweeney’s ongoing tensions with the New Jersey Education Association, which opposed his bid for Senate re-election in 2017, proved too much for Sweeney to overcome.

Reports of tensions between the two camps persist, even as both sides contend that all is well.

Senate Majority Leader Loretta Weinberg (D), a Sweeney ally and a no-nonsense veteran of the upper house — visitors to her office are greeted by a poster reading, “Some call it bitching, I call it motivational speaking” — is happy to have an ally in the governor’s mansion. However, to call her feelings toward Murphy anything north of lukewarm would be a stretch.

She told HuffPost that while she is impressed with the new governor, his “extremely diverse” Cabinet and his diplomatic style (“He’s great on texting ― I got a happy birthday text from him”), reservations remain.

“I think legislative leadership needs a little bit more face time with him, not just electronic,” Weinberg said. She pointedly added that most of Murphy’s staffers lack any meaningful experience in the governor’s mansion.

It’s this kind of criticism, made freely by Trenton Democrats, that gives the impression sometimes that New Jersey doesn’t have single-party rule so much as it has a coalition government.

The governor, naturally, takes issue with characterizations of his relationship with the legislature as strained.

“The relationship is outstanding. We are literally talking to leadership on both sides of the aisle,” Murphy said. He and Democratic leaders are in lockstep, he said, in counteracting the “ridiculous” tax law passed by congressional Republicans.

But officials close to Democratic leadership say that Murphy’s plans for marijuana and the minimum wage may meet resistance, with some influential members of the legislature’s Black Caucus raising concerns over legalization and other centrist members balking at a minimum wage hike. Though dominated by Democrats, the legislature is by no means a bastion of progressive politics.

Weinberg insists that marijuana legalization doesn’t have the votes yet. “It doesn’t mean we’re not going to get [the votes] at some point,” she added, “but I think people have questions and I think those questions deserve good answers based upon whatever science we can find out.”

Intra-Democratic tension in Trenton isn’t new. In 2006, the state government shut down because another Goldman Sachs exec-turned-Democratic governor, Jon Corzine, came to an impasse with Democrats in the legislature over raising the state sales tax. Corzine insisted that an increase was needed to cover a $4.5 billion budget deficit, while his counterparts in Trenton opposed the hike.

Murphy’s first budget, which he unveiled on March 13, highlighted similar divisions. Officials on all sides insist that the current tensions pale in comparison to previous intra-party squabbles. But like Corzine, Murphy is proposing a sales tax hike, and his plan to increase taxes on millionaires has met some opposition from Senate President Sweeney and Assembly Speaker Craig Coughlin (D).

Here, Murphy’s boringness might also serve him well. Although Democratic operatives describe him as an unapologetic liberal, they still see him as much less hardheaded than Corzine. And Murphy has put his diplomatic skills to good use, making strong connections with many of the state’s most powerful interest groups (see: New Jersey Education Association), which could prove useful in rallying support for his agenda.

Hetty Rosenstein, the director of the Communications Workers of America’s Trenton operations, said that the governor’s outreach during his campaign and transition was “impressive,” and that many liberal organizations felt engaged by him.

Indeed, it’s hard to envision a legislative session that doesn’t tick through a sizable laundry list of progressive to-dos. But the leadership tension will continue to be a source of intrigue. More than a few people close to the parties involved speculated that Sweeney could launch a primary challenge against Murphy in 2021 if their relationship or Murphy’s public standing deteriorates.

A lot of national Democratic hopes will be pinned on Murphy and the New Jersey legislature over the coming months and years, if only because there aren’t many other places to pin said hopes. Only eight states have both a Democratic governor and a Democratic-controlled legislature, compared with 26 capitals that are fully under Republican rule. With just under three years of the decidedly conservative and decidedly unboring Trump administration to go, anyone looking for a progressive and unfussy alternative to the commander-in-chief can look across the Hudson from Trump Tower.

“We’re not consciously trying to be an alternative template,” Murphy said of the national attention his new administration has garnered. “But we can’t help but react to what’s coming at us.”

Love HuffPost? Become a founding member of HuffPost Plus today.

This article originally appeared on HuffPost.