Jeremy Lin's Dreads And Kenyon Martin's Chinese Tattoo Are A False Equivalency

Updated: Oct. 12, 2017

After a dispute over cultural appropriation broke out on social media between Brooklyn Nets guard Jeremy Lin and former Net Kenyon Martin, the internet naturally separated into respective camps over who was “right.” Although popular opinion points to the belief that Lin sank his shots better and won the argument, with some people leaving racist comments on Martin’s social media accounts, the reality is that they were both in the wrong.

The scuffle between the two men over the fact that Lin has dreadlocks and Martin has Chinese tattoos highlighted a simple fact: both men were guilty of appropriating from each other’s cultures.

Yet there’s a certain reality that belies the accord the two reached: There’s a false equivalency in saying Chinese tattoos on a black man and dreadlocks on a Chinese-American man are the same type of offense.

Lin implied the two were showing equal signs of “respect” for each other’s cultures, and the media and commenters largely took his side.

Although the two ultimately arrived at a place of empathy and understanding, it’s important to note that Martin was unfairly vilified because he had a point when he initially called Lin out for his locs. Neither of their actions ― culturally appropriating tattoos or dreads ― were signs of “respect.”

But borrowing a cultural marker like dreadlocks, which embody both joy and struggle unique to the black community, is not the same as having a Chinese tattoo, a symbol that doesn’t carry the same weight of oppression. Yes, appropriating Chinese culture through a tattoo is exoticizing and insensitive. But the the act of putting on and taking off dreadlocks ― which are related to the systematic economic and social oppression of a racial group ― demonstrates a greater level of disregard.

The matchup between the two began last week when Lin wrote an essay about why he got dreads. In the The Player’s Tribune, he admitted he hadn’t considered the issue of cultural appropriation, that he had talked with a number of people about his decision and pointed out he was able to empathize.“I know how it feels when people don’t take the time to understand the people and history behind my culture,” he wrote. “It’s easy to brush some of these things off as ‘jokes,’ but eventually they add up. And the full effect of them can make you feel like you’re worth less than others, and that your voice matters less than others.”

Three days later, Martin weighed in and said Lin’s dreadlocks pointed to the fact he wanted to “be black.”

“Do I need to remind this damn boy that his last name Lin?” Martin asked in a YouTube video. “Come on man, somebody need to tell him, like, ‘Alright bro, we get it. You wanna be black.’ Like, we get it. But the last name is Lin.”

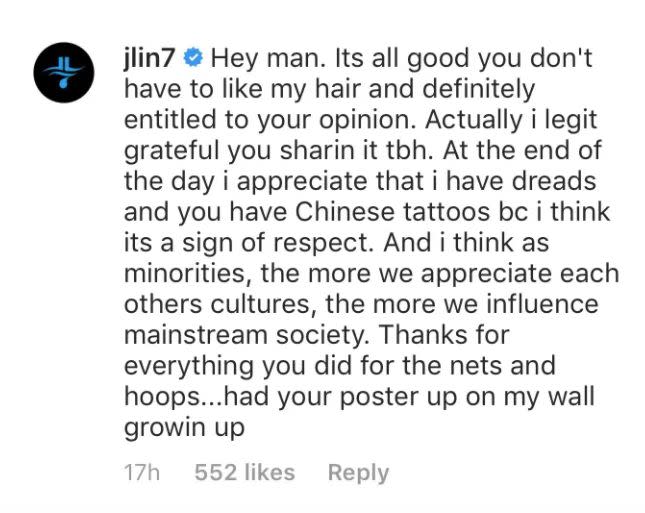

In a comment on Martin’s instagram video that has since been deleted but captured by NetsDaily, Lin responded saying he was grateful for Martin’s opinion and then went on to point out that Martin has Chinese tattoos.

“At the end of the day, I appreciate that I have dreads and you have Chinese tattoos bc I think it’s a sign of respect,” Lin wrote in a comment social media. “And I think as minorities, the more we appreciate each other’s cultures, the more we influence mainstream society.”

To Lin’s point, the adoption of Chinese tattoos, tribal tattoos and other similar varieties is problematic. It doesn’t cross a using-someone-else’s-culture-for-personal-gain line in the same way, say, Kylie and Kendall Jenner’s Chinese takeout purse does. But the issue of appropriation boils down to the fact that most Asian people don’t like their culture reduced to an accessory. There’s also the issue of modern-day and historical discrimination against Chinese people, so turning Chinese customs into an accessory can come across as cherry-picking parts of a culture to accept ― rather than embracing an ethnic group as a whole. And ultimately, a practice like making Chinese tattoos a Western trend without an actual connection to the culture can feel exoticizing.

But Lin’s retort to Martin’s criticism was basically saying the tattoos and dreads are uniform in their demonstration of “respect,” and that’s just not accurate. Yes, cultural appropriation of Asian culture is oppressive in that exoticizing a culture can create a depiction of Asians as “others” or perpetual foreigners. But Asian-Americans are not held down by this characterization in the same way black people are for something as fixed as hair ― and the struggle it represents.

Dreadlocks, which are essentially twisted locks of hair, are more than just a hairstyle. They have become symbolic of blackness and black culture and while some wear them for aesthetic reasons, others can have a deep cultural and spiritual connection to them. The style itself is widely worn by many Rastafarians, a religious movement bred in Jamaica, and, for some among them, it can represent a resistance to Western or Euro-centric hairstyles while honoring their roots.

And the politics of black hair persist today. Black hair, like blackness itself, is inherently political and many people of color have faced real consequences for how they choose to wear their hair. Last year, a federal appeals court maintained in a ruling that it is OK for employers to discriminate against those with locs, meaning individuals with dreads can be and sometimes are denied jobs.

While Lin did seek out advice and input firsthand, he still decided to get dreadlocks because he saw it as a sign of “respect.” But the real respect, comes with truly understanding the importance and history behind something as culturally sensitive as dreadlocks. Lin didn’t heighten consciousness around any of this in the letter he wrote and Martin did not make it a point in his remarks. Martin did admit late last week that he used a poor choice of words in a video posted on TMZ’s website.

“Wasn’t really saying it to him. I just made a blanket statement, which I probably should’ve reached out to him,” Martin said. “But the man has dreadlocks, and I thought it was hilarious. Nothing more, nothing less than I thought it was hilarious. I made a statement ... wording probably was bad that I used, saying that he was trying to be black. Wasn’t my intention to be racist or anything like that.”

In the end, both athletes said they learned a lesson in race, appreciation and appropriation. Lin called for greater tolerance and understanding, telling ESPN, “I’d love to see all other races become a part of these conversations, when it’s not necessarily about that specific race.”

Love HuffPost? Become a founding member of HuffPost Plus today.

This article originally appeared on HuffPost.