How Do The Iowa Caucuses Work? This Year It's A Little Different.

DES MOINES, Iowa ― Every four years, reporters converge on Iowa to cover the charming intricacies of the state’s partisan caucuses, where a relatively small group of dedicated voters gets the first say in the country on who will be either the Republican or Democratic presidential nominee.

But the complexity of the caucuses, which are effectively public, in-person voter surveys run by the two major political parties, have made them the targets of reformers eager to expand voter participation and increase confidence in the system.

Calls to overhaul the caucuses ramped up in the wake of Hillary Clinton’s razor-thin victory over Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) in 2016.

In response, the Democratic Party in all but a handful of states has done away with caucuses.

In Iowa, for decades the face of the caucus system, the Democratic Party stuck with the practice, but adopted a series of reforms designed to increase access and the transparency of the results.

Now, Iowa politics watchers worry that those fixes will create still more problems.

“They are taking a process that is already complex and confusing, and making it even more complex and confusing,” said Dennis Goldford, a politics professor at Drake University in Des Moines, who specializes in the caucuses.

Below is a guide to the Iowa caucuses, the changes and how they could affect who claims victory:

What Are The Iowa Caucuses?

In Iowa, Democrats have used a caucus as the vehicle for voters to weigh in on the national presidential primary since 1972, and Republicans adopted it in 1976.

This year, both parties will hold their caucuses on Monday at 7 p.m. Central Standard Time (though with President Donald Trump seeking reelection, the GOP confab is mostly a formality).

But there are key differences in the way the two major political parties conduct their caucuses in Iowa.

The Republican Iowa caucuses are little more than an informal primary, with voters casting ballots for their preferred candidates.

In Iowa’s Democratic caucuses, voters express their candidate preference by congregating in a corner of the room at a caucus location. The people running the caucus then manually count the number of people in each corner and, if a candidate has not received more than 15% of the vote, their supporters must either realign with another presidential hopeful who is viable, attract supporters of another candidate to their corner so they surpass the threshold of viability, or caucus as “uncommitted” to any candidate. Particularly at larger caucus sites, eliminating unviable candidates and tallying up the official preferences often takes hours, lasting well into the night.

Unlike secret-ballot votes, the Democratic caucuses are open to members of the media and emissaries of the presidential campaigns. As a result, they are often hubs of campaign organizing activity and dealmaking. Candidates train staffers and recruit volunteers they anoint “precinct chairmen” to ensure discipline among their backers at all 1,678 precincts where caucuses are held and nudge the supporters of unviable candidates into their corner.

Until this year’s caucuses, the Iowa Democratic Party did not reveal the raw totals received by each candidate in the numerous precincts across the state. The only metric for assessing a candidate’s performance in the caucuses was what’s known as “state delegate equivalents” ― the share of delegates to the state party convention won by an individual candidate. Those delegates subsequently determine the number of pledged delegates a candidate gets to send to the Democratic National Convention in the summer of a presidential election year. And that final convention tally formally decides who the party’s presidential nominee is.

Each caucus precinct is worth a certain number of “state delegate equivalents” based on an average of the precinct’s share of the general election population in the two previous elections.

How The Democratic Caucuses Have Changed Since 2016

One of the biggest sources of controversy after the 2016 Democratic caucuses was a sense among Sanders’ supporters that the formula for allotting delegates by precinct did not accurately reflect the depth of Sanders’ support. The close nature of the vote added to the confusion, with coin tosses breaking ties in at least a dozen caucus precincts. Sanders himself called for a release of the raw vote total late on the night of the caucuses.

It was the tip of the iceberg when it came to Sanders’ grievances with the way the presidential primary was conducted. In July 2016, the Vermont senator and his allies succeeded in pressuring the Democratic National Committee into convening a Unity and Reform Commission that would recommend changes to the party’s presidential nominating process.

After prolonged debate and deliberation, the DNC approved a slate of reforms in August 2018 that were best known for disempowering “super delegates” ― a group of elected officials and party insiders that had been free to nominate a Democratic presidential candidate not chosen by their state’s residents. But the central party body also required state parties with caucuses to make their systems more transparent and accessible.

The Iowa Democratic Party responded to the reform mandate by announcing that, in addition to its practice of releasing each candidate’s “state delegate equivalents,” the party will reveal candidates’ raw vote totals in the first round of caucusing and after the “realignment” when caucusgoers backing an unviable candidate choose someone new or go home.

Unlike in previous cycles, the party has forbidden caucusgoers from changing their preference if the candidate they back surpasses the 15% viability threshold during the first round of caucusing. To ensure the finality of those results and to create a paper trail that can subsequently be audited in the event of a dispute, those caucusgoers whose preferred candidate emerges viable would submit their official choice on a “Presidential Preference Card.”

Finally, the Iowa Democratic Party approved the creation of “satellite” caucuses that allow caucusgoers to express their preferences at times and locations that are more convenient for them. Any campaign, organization or constituent group could apply to have the party authorize a satellite site. The party ultimately signed off on 87 satellite sites in locations ranging from labor union halls and nursing homes to churches, mosques, restaurants, college campuses and private homes. The first caucusgoer will make their preference known at a satellite caucus in Tbilisi, Georgia, at 10 a.m. CST. Other Iowans living outside of the state will caucus in Paris; Glasgow, Scotland; and locations in the states of Arizona, California, Florida, Illinois, New York, Tennessee, Wisconsin, Rhode Island, Michigan, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Virginia, and Pennsylvania, as well as Washington, D.C.

Initially, the Democratic parties of Iowa and Nevada ― another caucus state ― had planned to hold six “virtual” caucuses that would allow caucusgoers to participate by phone. But the state parties reconsidered after the DNC signaled that it would veto the idea, citing fears that the phone-based caucuses would be vulnerable to hackers.

Why The Changes Matter

While only racking up “state delegate equivalents” can help a candidate advance toward the Democratic presidential nomination, presidential candidates also try to use the Iowa results to shape the narrative about their candidacy.

The inclusion of new results data could create advantages for some candidates and disadvantages for others. A candidate who does not win the greatest number of “state delegate equivalents” might tout winning the raw vote ― in either the first or final alignments ― in much the same way that a presidential candidate who loses the Electoral College points to a popular vote win.

What Goldford and some other Iowans fear is that by creating multiple bases for declaring victory, the new caucus results reporting system will sow confusion and resentment, undermining confidence in the process rather than bolstering it.

“There’ll be a lot of controversy about that,” said Dave Yepsen, an Iowa politics specialist and host of the news discussion television show, “Iowa Press.” “It could be a muddied result.”

Another variable is how the addition of satellite caucuses will affect turnout, particularly of the sort needed by candidates banking on a surge of new or infrequent voters.

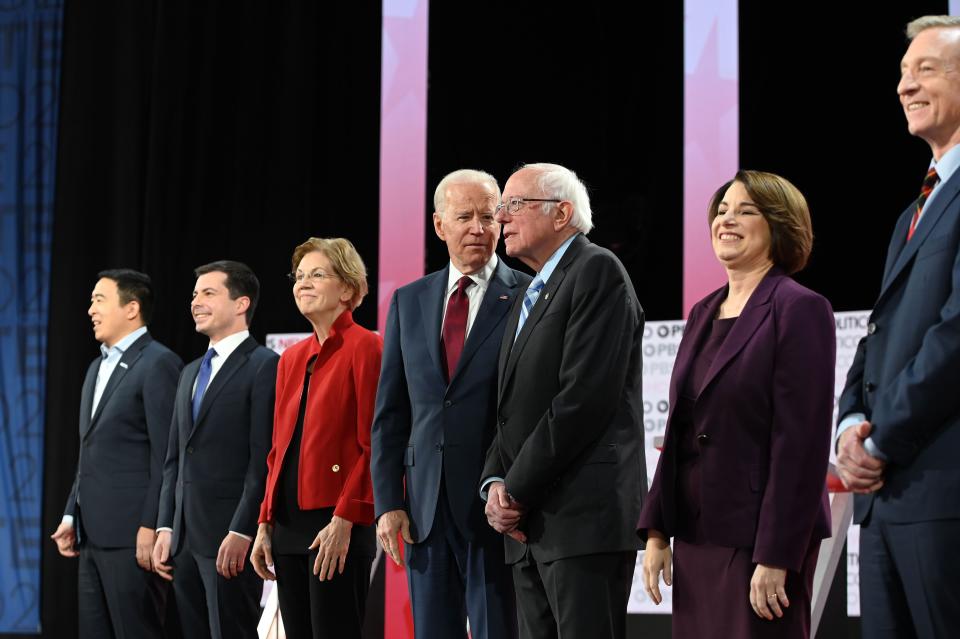

Of the four candidates leading in public polls ahead of the caucuses, Sanders has invested the most in courting less politically engaged constituencies. His campaign claims its success hinges on extraordinary voter turnout, particularly on the state’s college campuses, where support for Sanders runs high.

To that end, his campaign has taken the lead in organizing several Spanish-language satellite caucuses, according to Iowa political director Oliver Hidalgo-Wohlleben.

What would high turnout look like?

The largest number of people to participate in the Democratic Iowa caucuses recently was about 240,000 people in 2008. In 2016, by contrast, roughly 171,000 Iowans participated.

Jeff Link, a Des Moines-based Democratic campaign strategist who has not endorsed a candidate, predicted the turnout on Monday is “going to be close to 2008” levels.

Love HuffPost? Become a founding member of HuffPost Plus today.

Also on HuffPost

Arizona State Capitol (Phoenix)

California State Capitol (Sacramento, Calif.)

Colorado State Capitol (Denver)

Delaware State Capitol (Dover, Del.)

Georgia State Capitol (Atlanta)

Hawaii State Capitol (Honolulu)

Idaho State Capitol (Boise, Idaho)

Indiana State Capitol (Indianapolis)

Iowa State Capitol (Des Moines, Iowa)

Kentucky State Capitol (Frankfort, Ky.)

Maryland State House (Annapolis, Md.)

Massachusetts State House (Boston)

Michigan State Capitol (Lansing, Mich.)

Minnesota State Capitol (St. Paul, Minn.)

Montana State Capitol (Helena, Mont.)

Nevada State Capitol (Carson City, Nev.)

New Hampshire State House (Concord, N.H.)

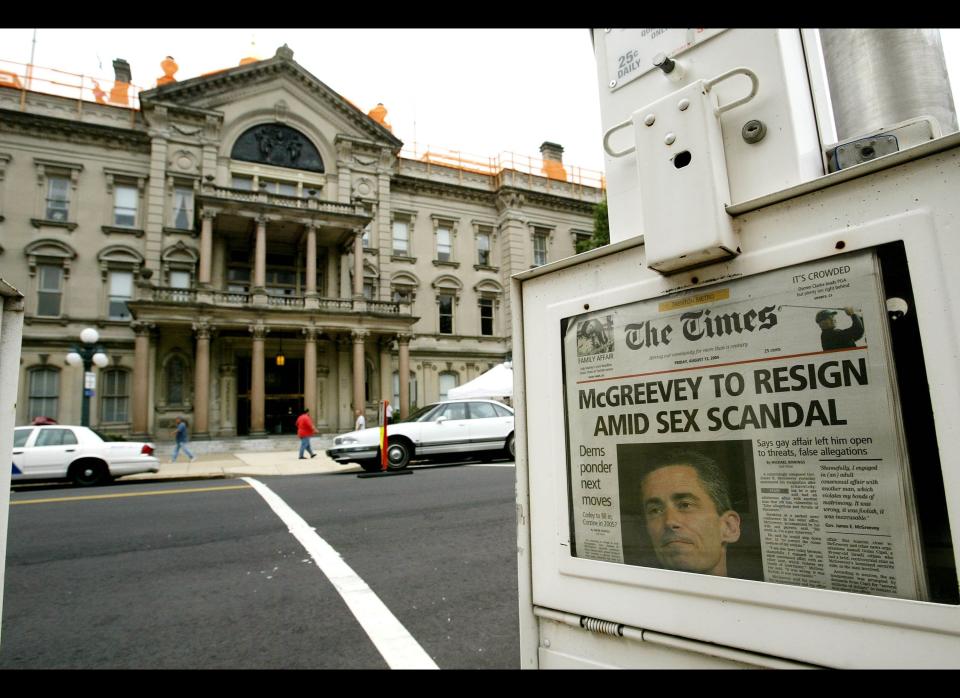

New Jersey State House (Trenton, N.J.)

New Mexico State Capitol (Santa Fe, N.M.)

New York State Capitol (Albany, N.Y.)

Ohio Statehouse (Columbus, Ohio)

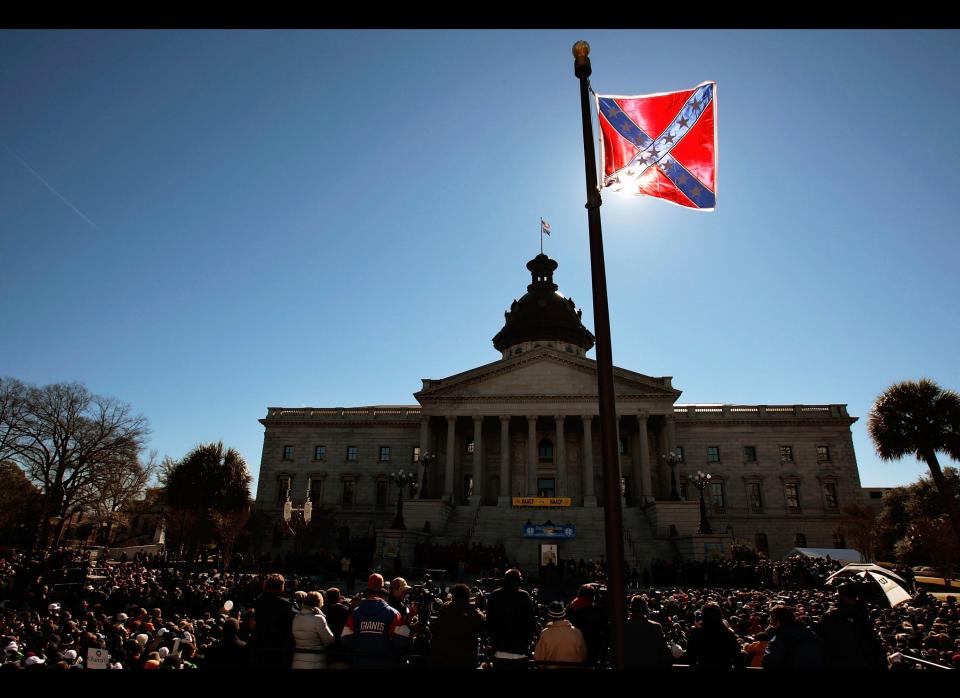

South Carolina State House (Columbia, S.C.)

Virginia State Capitol (Richmond, Va.)

Wyoming State Capitol (Cheyenne, Wyo.)

This article originally appeared on HuffPost.