Hospitals Are Releasing Homeless Patients Back To The Streets. There's A Better Way.

LOS ANGELES — Two years ago, Sherolyn Scott lost the apartment she had been living in for 16 years due to rising rent costs. She took the money from her security deposit and started sleeping in motels, but when that money was gone, she resorted to parks and porches.

Sleeping outdoors, unprotected, set off a cascade of medical emergencies, often the result of violence. Attackers raped Scott, she said, and as she was recovering from the assault, she suffered a stroke. Later, robbers beat her so viciously that she ended up with her jaw wired shut.

Each of these events sent Scott to the hospital, after which she was released back to a life on the streets.

It wasn’t until the third hospital visit that police, worried that those who assaulted and robbed Scott would return to hurt her again, suggested the hospital find somewhere for her to stay after discharge.

The hospital then referred Scott to a recuperative care facility ― a temporary shelter with nursing staff and social workers ― run by a local nonprofit, the National Health Foundation. She spent the next four months recovering and working with a housing program. At the end of her stay, she was able to move into her own apartment in South Los Angeles. Scott, now 60 years old, believes she wouldn’t be alive today if it hadn’t been for recuperative care.

“If they had sent me back to the streets one more time, I [would] be dead,” Scott said.

People who don’t have their own homes to return to after a hospital stay may be transported to homeless shelters, although a significant minority are released directly back onto the streets. A survey among 98 homeless people who had been hospitalized in New Haven found that 67 percent stayed in a homeless shelter the first night after being discharged from the hospital, while 11 percent slept on the street.

Both crowded, chaotic shelters and the street are obviously inappropriate places for medical recovery, which can have serious consequences for the patient, including a return to the hospital. Being homeless can increase the odds of re-hospitalization within 30 days almost four-fold.

One small study that followed homeless people after hospitalization in North Carolina found that they ended up living in church closets, ill-prepared family homes, addiction recovery centers or homeless shelters. Their recovery times were often prolonged because of infection, re-hospitalization, falls and lack of basic assistance.

This hospital-to-street pipeline also perpetuates homelessness. Repeated bouts of illness and injury can prevent people from finding or keeping a job or even navigating the maze of social services a city may offer, experts say.

In an attempt to fill the gap between acute care at a hospital and life on the street, nonprofits, funded by a mix of private and public money, are starting to open recuperative care facilities like the one Scott used. These centers provide services that homeless shelters cannot, including semi-private rooms and more support staff to help people with basic needs while they recover.

Recuperative care facilities are not a new idea. The first U.S. programs began cropping up in the mid-1980s, and there are now at least 78 known programs in 29 states and Washington, D.C.

Like most services for the homeless, these facilities suffer from a lack of funding, and the data to prove their effectiveness is expensive and difficult to gather. But as the number of homeless continues to grow in major American metropolitan regions, officials and experts keep trying to identify and invest in programs that help people survive and exit homelessness.

California leads the country among states that have invested in recup facilities, as they are sometimes called. At last count in 2016, it had 23 known recuperative care programs. By comparison, Florida, the state with the second largest number of programs, had five.

Los Angeles County has the highest number of recuperative care beds in the state, which makes sense considering it also has the second-highest homeless population and the greatest number of unsheltered homeless people in the nation. If recup facilities can work here, experts hope to hold up the state as a model for the rest of the country.

“California has the most respite programs, and that’s partly related to the population of homeless in the state, but also the innovation in the state as well,” said Julia Dobbins, an expert on respite care with the National Health Care for the Homeless Council. “I think other states are interested in emulating [that].”

Recuperative care saves money

The benefits of entering recuperative care are undeniable. According to LA County’s own records, about 50 percent of people who spend time in a recuperative care facility go on to secure permanent housing. For hospitals both private and public, recuperative care also has the potential to lower overall costs and decrease the rate of hospital readmission.

Health officials estimate that each day in a bed at LA County’s safety net hospital costs the county more than $3,000, while a bed at a recuperative care facility averages about $150 per day.

“We’re spending a lot of money on emergency services for these vulnerable homeless individuals,” said Libby Boyce, director of access, referral and engagement in the Housing for Health division of the Los Angeles County Department of Health Services.

“More thoughtful and impactful solutions are not only the right thing to do,” Boyce said, “but we believe that it results in significant cost avoidance.”

Those cost savings have motivated local safety net programs, insurance companies and private hospitals to invest in recuperative care to lower their own expenses.

Even the voters saw the light in LA County. Faced with a growing homeless population, voters decided in 2017 to tax themselves an extra quarter-cent to fund homeless services. That steady stream of funding will help the county double its recuperative care bed count from 500 to 1,000 within the next two years.

Finding funds is a struggle

But nationally investments in these programs have come in fits and starts, propelled by factors like the cluster of controversies over patient dumping in 2007, implementation of the Affordable Care Act penalties to prevent hospital readmission within 30 days in 2013, and Medicaid expansion, which opened up a new source of funding in states that chose to participate in 2014.

Most recup facilities must rely on a hodgepodge of public and private money that includes funding from private hospitals, community health grants from Medicaid and Medicare, private donations, local and state government spending, and donations from faith communities, according to a National Health Care for the Homeless Council report.

Currently, LA County ― again, the region with the largest investment in this kind of care ― has dedicated funding to pay for only 500 beds in recuperative care. That’s a drop in the bucket given the approximately 55,000 county residents without a home.

Private hospitals in Los Angeles pay for recuperative care as well, contracting with the National Health Foundation, the nonprofit that helped Scott get her life back. But counties and hospitals can’t cover the start-up costs for these facilities. The foundation’s latest facility in Los Angeles required a coordinated effort of nonprofits to fund the construction ― and eventually operations for free or at-cost. That massive effort will result in just 100 more beds.

Because these are still considered experimental programs, there is no licensing structure or regulations for recuperative care. Facilities range from motel rooms to a set of shelter beds to converted homes, according to the National Health Care for the Homeless Council.

Gaining Medicaid reimbursement would be the next big step, experts say. With that, the recuperative care model would have the steady, sustained support it needs to make a national impact on homeless people’s lives. But there’s a Catch-22: Solid data are needed to justify Medicaid reimbursement as well as widespread investment in recuperative care, but gathering that data from far-flung, uncoordinated and scattershot programs requires a lot of money.

Henry Fader, a health care lawyer at Pepper Hamilton in Philadelphia and a member of the steering committee of the Respite Care Providers’ Network, said raising money to do this proof-of-concept research is a priority for the network. But he was pessimistic about the chances of being recognized by the federal Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

“Not only would government have to feel comfortable that it was a viable service, but then the intermediaries, insurance companies and nonprofits would also have to agree to split some of their money,” Fader said.

For now, even small and underfunded recuperative care centers can deliver powerful results for the people who have access.

In Los Angeles, Scott had a safe, clean and comfortable space to live for four months, as she slowly regained use of her jaw. In addition to her physical recovery, she said the facility helped her learn “how to live again.” With simple rules to follow, like keeping her room clean, and counselors to offer mental help, it let her heal from the trauma and disorder of living on the street for two years.

Now that she’s in her own apartment again, her two adult children are living with her — as well as a brand-new grandson, born two months ago, whom she gets to watch grow up.

“I had to go through all the steps of the program, but here I am today,” Scott said. “I have my own apartment, I have my children with me, and mentally and physically [I’m] OK.”

Also on HuffPost

Precious, 2018

Meghan, 2018

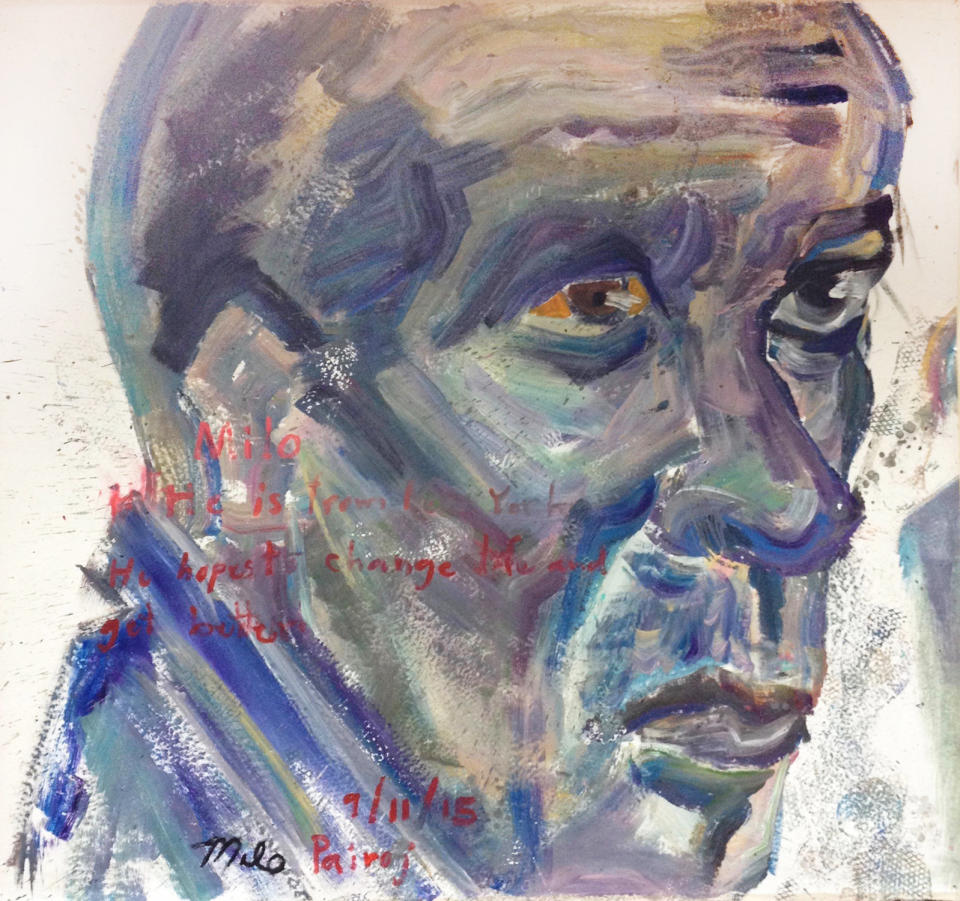

Milo, 2015

Leslie, 2018

![“Don't judge a book by its cover, because you never know what a person has been through. Prior to being homeless, I worked for the attorney general. I had good jobs. I started working at 12 years old. But the drugs ... I ran into a guy with fast money, and didn't have to work, everything was provided. So I was exposed to the drug life, and got caught up in the life I was exposed to. Crack is so powerful, you get that high that one time, and you never get it again. So you're chasing that high. It was rough being out on the streets, because you never knew who you were going to bump into. For 11 years, I drank every day and smoked every day. I thought I was going to die on the streets. But God said no. And he gave me a second chance at life. I've been clean for 27 years. I got my children back, I went to school. Got my first master's. I'm working on my second master's, to get my [master's in social work]. I'm currently working with homeless men. I have a population of 177 men and I have the daunting task of making sure they have housing and that they are treated with dignity. Every now and then, I have to give myself a refresher course. Because you can become numb to the pain, numb to the way some people are living, and then I have to remind myself, Leslie, you used to be a homeless woman, too, so if there was hope for you, there's hope for them.” -- Leslie, 2018](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/7h3nQuiQKrXqS39wPq7RsQ--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MA--/https://img.huffingtonpost.com/asset/5abc06642000002d00eb34c1.jpg)

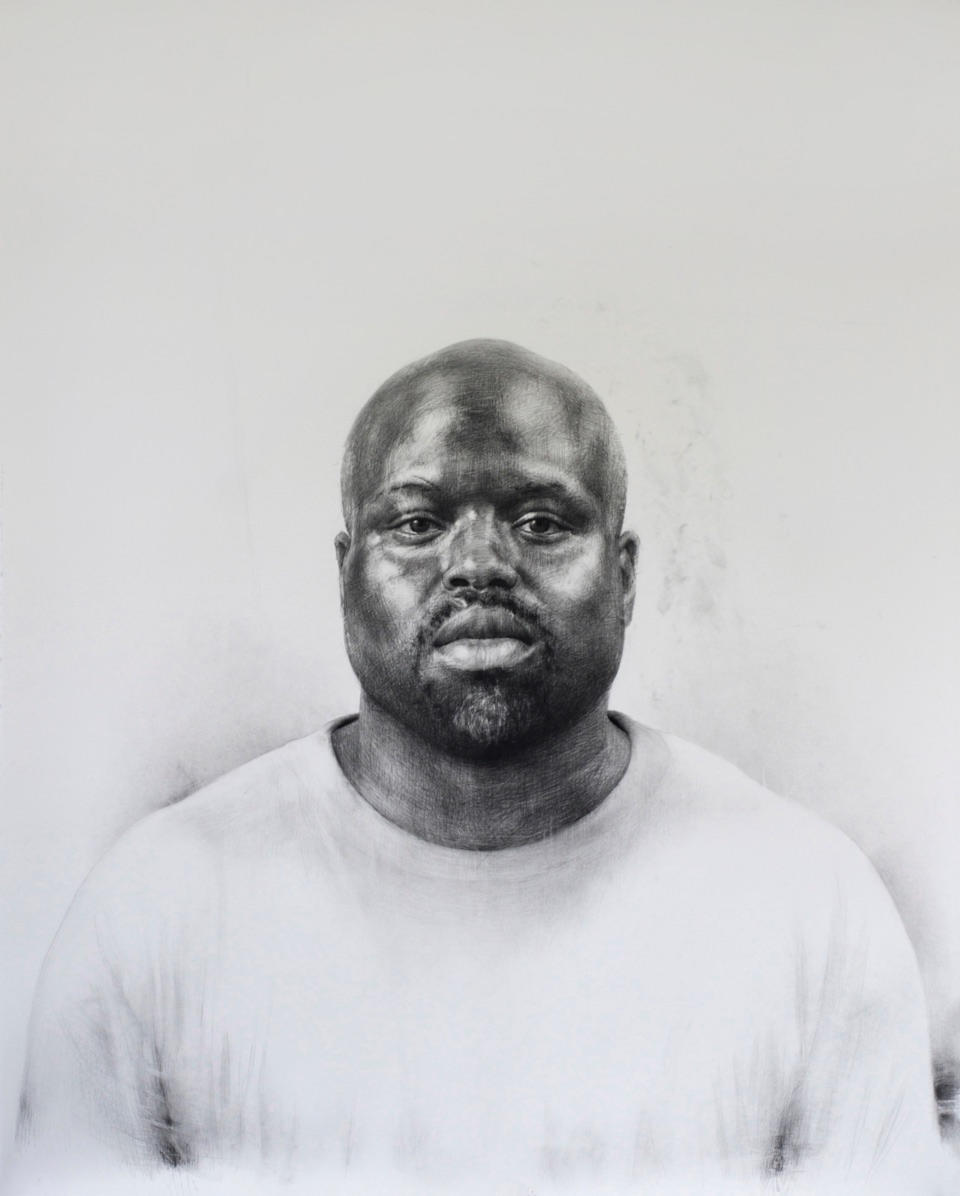

Anthony, 2015

Declan, 2015

Love HuffPost? Become a founding member of HuffPost Plus today.

This article originally appeared on HuffPost.