Here’s What Happens When Trump And Congress Clash Over Executive Privilege

President Donald Trump and House Democrats are headed for a showdown over the House Judiciary Committee’s pursuit of records to investigate the president’s corruption. Trump has already dismissed the document requests sent to 81 individuals, entities and government agencies as “a big, fat, fishing expedition desperately in search of a crime.”

And he’ll likely do whatever he can to hinder them.

Trump may assert executive privilege over a wide swath of his documents and communications to prevent handing them over to congressional investigators. Such an assertion could wind up in a drawn-out legal process in the courts.

Every president has invoked some form of executive privilege in order to protect the confidentiality of executive branch decision-making ― and to hamstring congressional investigators. The privilege cannot be found in the Constitution, but is based on the idea that the president is due some confidentiality to run the executive branch and that allows him or her to prevent the release of certain documents and communications related to that duty.

The privilege covers only communications within the executive branch or by the president, and not private parties. This means that Trump could not assert executive privilege over information from his personal business or individuals like his adult sons Donald Trump, Jr. and Eric Trump.

Executive privilege was first invoked by President George Washington to prevent the disclosure of information about the Northwest Indian War and the Jay Treaty to the first congressional oversight investigations. The term “executive privilege” came later, when President Dwight Eisenhower’s attorney general William Rogers used it to describe how the president could prevent aides from testifying to committees, including those led by Sen. Joseph McCarthy (R-Wisc.).

“It is essential to efficient and effective administration that employees of the executive branch be completely candid in advising each other on official matters,” Eisenhower said in 1954.

For most of American history, fights over executive privilege played out as a political tug-of-war. Today, they are governed by the rules set out by the Supreme Court in its unanimous 1974 U.S. v. Nixon decision, plus guidelines subsequently issued by the Department of Justice and a set of norms acknowledged by the executive and legislative branches.

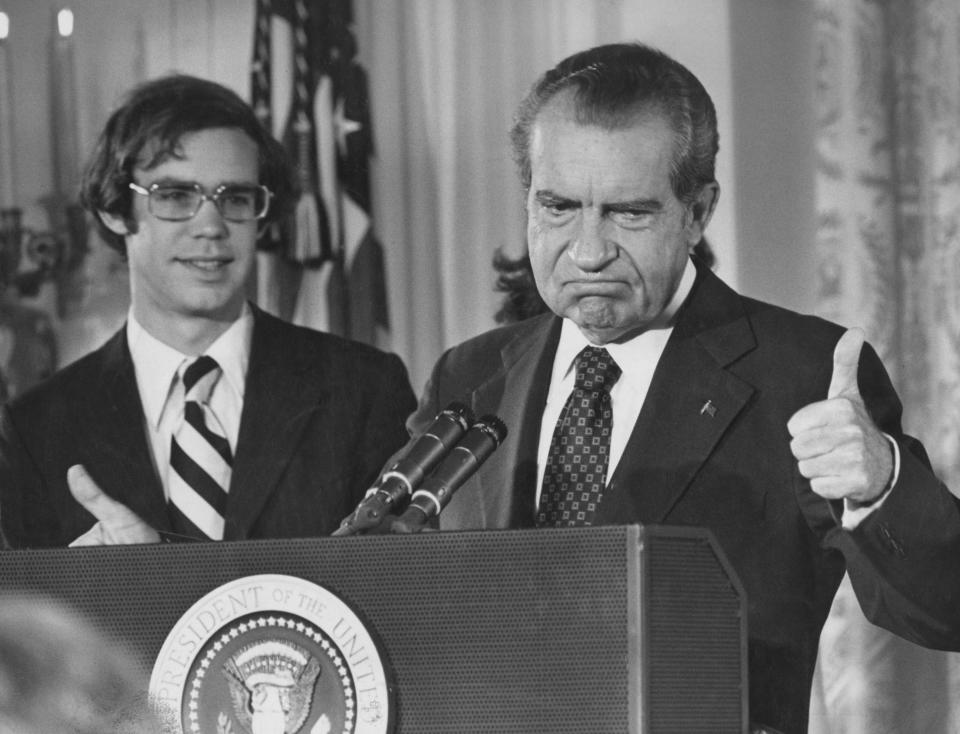

The court first affirmed a constitutional right to executive privilege in U.S. v. Nixon. The decision stated that certain executive branch communications could be withheld from Congress and other entities, but rejected an “absolute, unqualified Presidential privilege of immunity from judicial process under all circumstances.” The case came about after Nixon claimed executive privilege over the White House tapes sought by special prosecutor Leon Jaworski. The court ruled that the tapes were not covered by executive privilege as the criminal investigation into the Watergate break-in could not be concluded without them. Nixon handed over the tapes, which proved his guilt, and within days he resigned the presidency.

Since then, congressional requests for disclosures from the executive branch and assertions of executive privilege have occurred under a set of guidelines and norms, which the two branches sometimes interpret differently.

Justice Department memos state that the executive is supposed to act in good faith in response to congressional requests and subpoenas. Documents are reviewed by agency lawyers who can request the president assert privilege over some or all of the information requested. Executive privilege should not be invoked where there is no valid legal basis, if the agency hasn’t already disclosed the information somewhere else or if the information could reveal wrongdoing or criminal acts, according to the guidelines.

That latter qualification could prove problematic for Trump, particularly when it comes to information related to his reimbursement of his ex-lawyer Michael Cohen’s hush money payments to the president’s alleged extramarital lovers.

Cohen pleaded guilty in 2018 to violating campaign finance laws for payments he made to quiet allegations against the president in order to aid his election. The charging documents against Cohen implicated the president in the crime for ordering Cohen to make the payments and then reimbursing him. Cohen provided checks to the House Oversight Committee indicating that the reimbursements occurred while Trump was president.

Documents that could implicate the president or any other executive branch official in a crime do not qualify for executive privilege. This has been standard practice going back to the standard set in U.S. v. Nixon and stated in legal memos produced by the Reagan administration, which mostly waived executive privilege for the Iran-Contra investigation.

If Trump decides to assert privilege over these documents or any other that Congress deems it has a right to access, the conflict could wind up in court.

Most of the time, fights between Congress and the executive over assertions of privilege are worked out in some way with the two parties coming to an agreement. It is actually very rare for them to be decided by judges.

The majority of major court challenges over executive privilege have come when the White House and other agencies sought to stop the disclosure of information to prosecutors, not Congress.

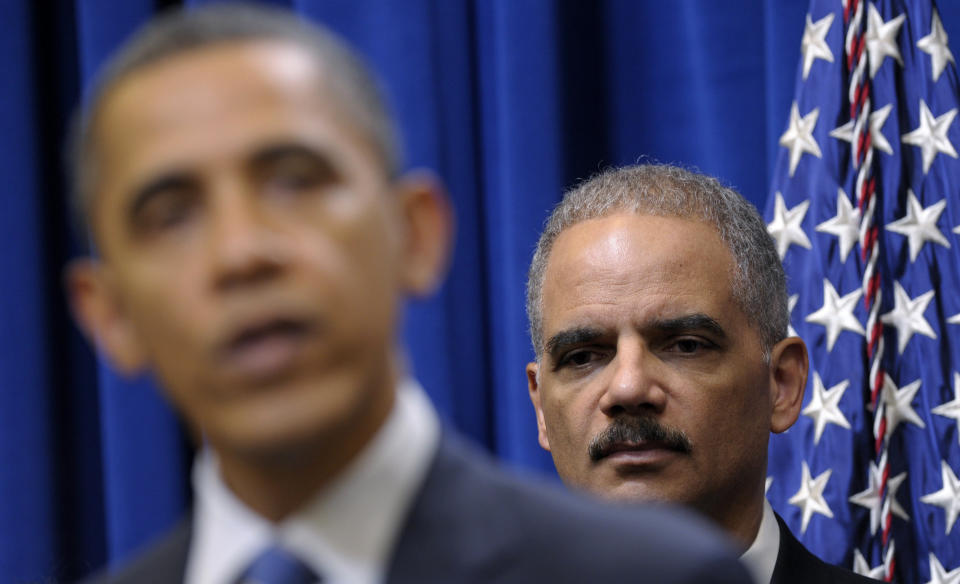

The most notable executive privilege case involving Congress came about after President Barack Obama invoked executive privilege in 2012 to refuse a congressional document request related to the gun-walking operation run by the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives known as Operation Fast and Furious. A district court judge ultimately ruled in 2016 that a subsequent inspector general report had made similar disclosures as requested by the committee, effectively mooting the claim of privilege.

But the most relevant case to the present investigation occurred just before U.S. v. Nixon, when the Senate Select Committee on Presidential Campaign Activities sued for the administration to turn over the White House tapes. A judge said the committee didn’t show that it had a valid interest in obtaining them and denied access to the tapes.

This latter ruling could become relevant if the House Judiciary Committee winds up stuck in a legal battle with the Trump administration’s potential assertions of executive privilege.

“There’s a very strong analysis to say if the committee were pursuing an impeachment proceeding that would give them a very strong need to have access to relevant information from a criminal investigation,” John Bies, chief counsel for American Oversight, a liberal accountability group, and a former deputy counsel for the Justice Department, said.

The House Judiciary Committee is where impeachment begins. Democrats aren’t calling this investigation an impeachment inquiry ― yet. But they have been clear that they are investigating the president’s corruption and any potential crimes he has committed. The purpose of the investigation and the fact that documents are being sought to determine if the president is a crook would give the committee extra weight before a court reviewing a challenge to claims of executive privilege.

It was certainly the view of many past presidents that if they faced an impeachment inquiry they would waive any assertion of confidentiality or executive privilege.

“[P]oint to any case where there is the slightest reason to suspect corruption or abuse of trust, no obstacle which I can remove shall be interposed to prevent the fullest scrutiny by all legal means,” President Andrew Jackson said. “The offices of all the departments will be opened to you, and every proper facility furnished for this purpose.”

Love HuffPost? Become a founding member of HuffPost Plus today.

This article originally appeared on HuffPost.