Parents In Northern Greece Say They Don't Want Refugee Children In Their Schools

As the new school year kicked off in Greece, the country’s Ministry of Education announced a plan to enroll 22,000 migrant and refugee children in schools around the country.

The children, who fled war and poverty, are stranded in camps and refugee centers all across Greece, where opportunities for learning have been limited.

But the ministry’s decision to help them gain access to formal education has already been met with resistance. Two parents associations in Oreokastro, a town on the outskirts of Thessaloniki in northern Greece, have issued statements saying they will not accept the 420 migrant and refugee children living in the area in their schools.

The two associations, for the 1st primary school of Paleokastro and 5th primary school of Oreokastro, said their decision was “unanimous” and threatened to occupy school premises to oppose the children’s entry.

HuffPost Greece contacted the parents associations to find out the reasoning behind their opposition.

Fotini Kitsiou, president of the Paleokastro school’s parents association, claimed the parents were primarily concerned about health: “These children have not been vaccinated and we are worried about diseases.” If refugee children met health and vaccination standards, she added, the parents would not have a problem with them attending school.

But she also mentioned cultural and religious differences as a reason for the parents’ opposition, saying, “These children are raised in a different way and they wouldn’t feel comfortable in our schools.”

Oreokastro Mayor Asterios Gavotsis said he believed the best solution would be for refugee children to attend classes in a separate location. If the government does not agree with the proposals Oreokastro residents have submitted, he warned, they will mobilize in protest.

Not everyone in town stands behind the two parents associations, however. Athanasios Tsolakidis, the president of the Union of Parents Associations of Oreokastro, told HuffPost Greece the two parents associations were “two isolated cases” and said their views do not resonate with the majority of parents associations in the area. Tsolakidis later resigned, citing attacks from the public.

Education Minister Nikos Filis said the groups’ opposition to admitting refugee children is “incomprehensible” and attributed it to lack of information and prejudice. “This attitude stands completely at odds with the love, solidarity and understanding that the great majority of Greek parents, students and teachers have shown [towards refugees] in our country,” he said.

According to Filis, the government’s integration plan already addresses health concerns and includes an immunization program. “We have taken all necessary measures,” he affirmed in a radio interview. “Refugee children will be received at schools, will be vaccinated and will have their teachers. We want them to play with the Greek children and they will gradually be introduced in classrooms. I don’t understand why parents would not accept these children at school.”

Meanwhile, the prosecutor’s office in Thessaloniki ordered an investigation on Wednesday into the two parents associations’ stance and the mayor of Oreokastro’s statements to determine whether their actions can be prosecuted under a law that prohibits hate speech and the incitement of racist violence.

A version of this story originally appeared on HuffPost Greece.

Also on HuffPost

"Child Labor": Anjar Refugee Camp, Lebanon

Bassam and Tamer started selling tissues after their father was injured during a shelling blitz in Syria. The brothers often work 12 hours and earn about $3 a day, and have faced abuse while on the job.

Farah weeds and clears land for sowing to support her family of 10. In this photo, she and Lubna pose as factory workers peeling oranges to make tinned fruit. These laborers often work 11-hour days for as little as $8 a day.

"What makes me very tired is that I have to keep bending down. When we try and stand up, they ask us to bend down," she said. "We spend the whole day like this. The money they give us is not enough."

Many of these working children are also forced to miss out on educational opportunities in order to work.

"Education is very important. I feel it is especially important for girls. When girls get education, they are respected in society," said Lubna. "Some girls even have jobs in factories. They shouldn't be working -- they should be studying."

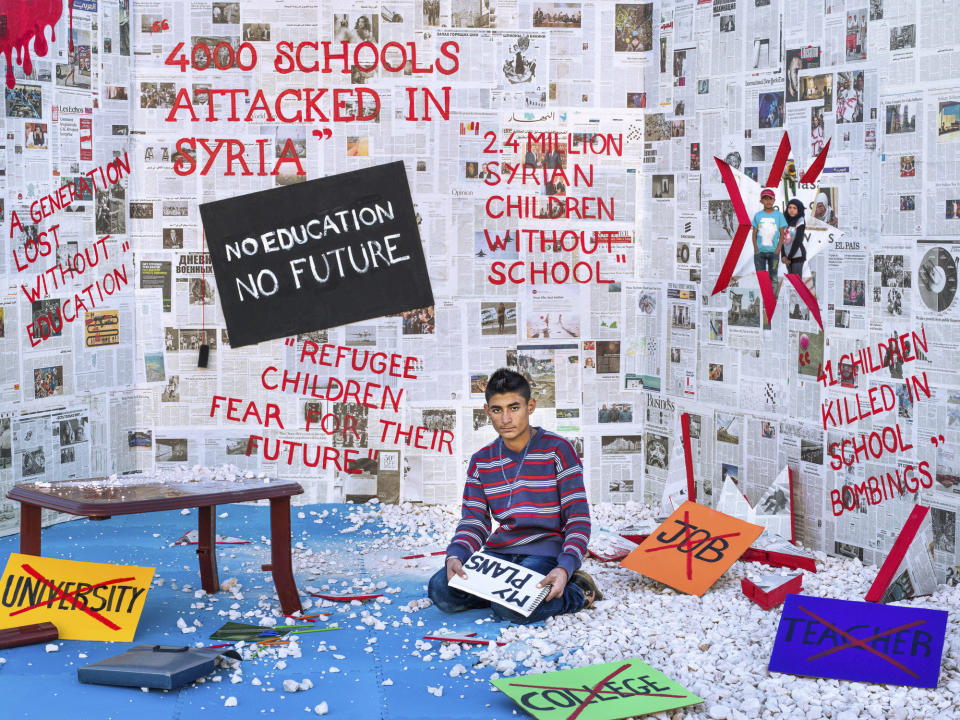

"Education": Bekaa Valley, Lebanon

Hatem says he is "sad and scared" about his destiny. He was enrolled in school for two years, but had to stop because his family couldn't afford to continue funding his education. He loved going to school -- his favorite subjects were math, English and Arabic. The teenager had planned to go to university and join the army, but those dreams are now gone.

"Because I am working now and I have been off school for three years, I have missed a lot of studying and won't be able to fill the gap," Hatem said. He now sells clothes at a marketplace and practices dabke, a modern Arab folk circle dance, to keep himself busy.

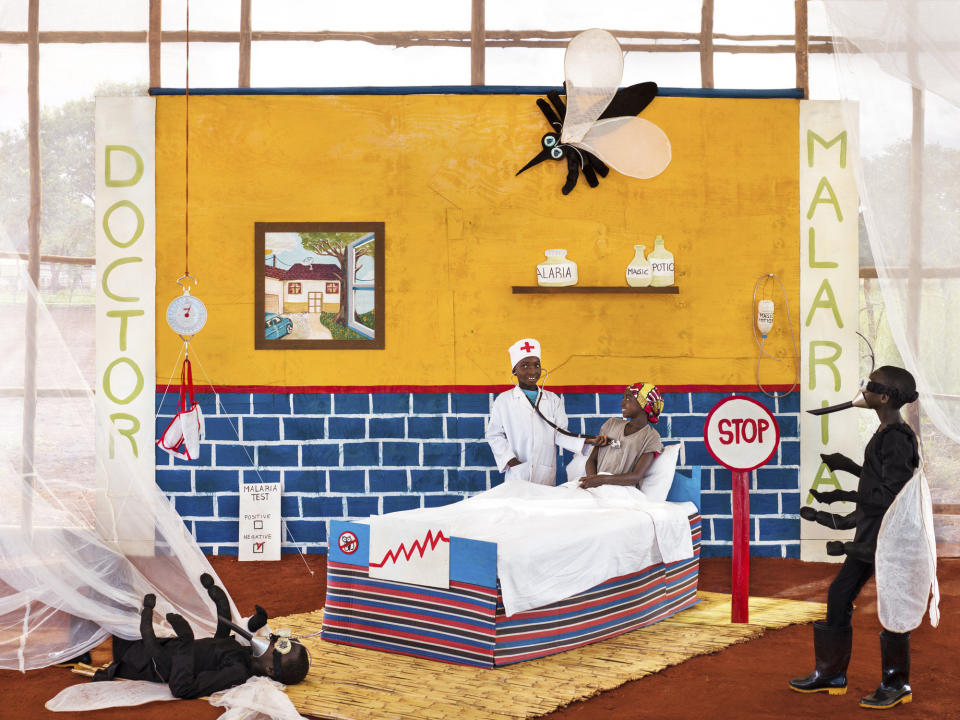

"Doctor Malaria": Nyarugusu Camp, Tanzania

When Anicet grows up, he wants to be a malaria doctor. In this image, he practices his dream job while his friends act as patients and mosquitoes.

"I want to be a doctor so that I can help people, make a difference and save lives," said Anicet. "This would make me a very important person and it would help me get something in my life."

"Firewood Collection": Nyarugusu Camp, Tanzania

Women and children who venture into the woods face many dangers, including assault.

Here, Esperanse, 15, shows what it is like for young girls and women to search for firewood in the forest surrounding the camp. She herself narrowly escaped an assault from three men.

"There are a lot of dangers that come when we go looking for firewood. ” says Esperanse. "We can get snakebites, or even encounter men who want to abuse us. Even if we’re able to escape and run away, we have to throw down all our firewood and we lose what we came for."

"My wish for the future is to have a place where I can live peacefully, a place where I can feel established, where I can feel that I'm at home, without all of these other problems," she added.

"The Mountain Journey": Nyarugusu Camp, Tanzania

![Children in Tanzania's Nyarugusu refugee camp re-enact crossing the mountains of Burundi on foot to seek refuge. Iveye, 6, is pictured on the far left carrying her 18-month-old sister, Rebecca, on her back. <br /><br />It took the siblings and their family five days to travel from their home to Tanzania, and the journey was far from easy.<br /><br />"When we reached the [Burundi-Tanzania] border, the police on the Burundian side would not let me cross into Tanzania with my daughters," the girls' father, Pierre, said. "So I separated from them and snuck across the border using a secret path. When I had safely reached the other side, I came out and signaled to Iveye and her sisters." <br /><br />"When they saw me, they ran across the border right under the gaze of the policemen who could do nothing to stop them," he added.](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/lLhOaOMyjv78Qm1FNbgoeQ--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MA--/https://img.huffingtonpost.com/asset/574486371a00002f00c297b3.jpg)

It took the siblings and their family five days to travel from their home to Tanzania, and the journey was far from easy.

"When we reached the [Burundi-Tanzania] border, the police on the Burundian side would not let me cross into Tanzania with my daughters," the girls' father, Pierre, said. "So I separated from them and snuck across the border using a secret path. When I had safely reached the other side, I came out and signaled to Iveye and her sisters."

"When they saw me, they ran across the border right under the gaze of the policemen who could do nothing to stop them," he added.

"Our Dream": Bekaa Valley, Lebanon

Both girls left Syria with their families to escape the violence. The house next to Samira's was shelled, killing the family next door.

Now the girls live in Lebanon's Bekaa Valley. "In Syria, when we got snow or wind, it was OK," Samira said. "But here, when the wind blows, we get a bit scared, as we're afraid the tent will get blown away."

"What Happened (The Past)": Bekaa Valley, Lebanon

When she was walking home one day, Walaa saw her school explode. This picture uses Walaa's original drawing to depict the moment her school was bombed.

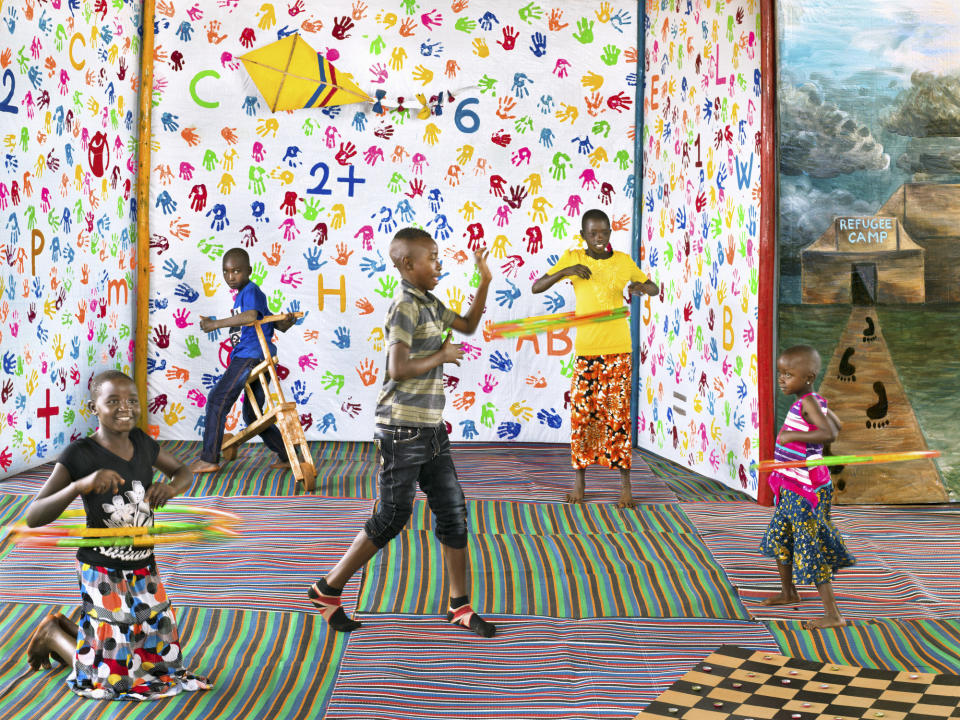

"CFS, An Oasis": Nyarugusu Camp, Tanzania

Fifteen-year-old Jacob, center, dreams of becoming a professional dancer. When he realized that he and his family had to flee Burundi, he performed dance routines in his local town market until he earned enough money to pay for his and his grandparents' transport to cross into Tanzania.

"I feel good about myself when I dance," said Jacob. "I feel that dancing will help me achieve my goals in life."

Love HuffPost? Become a founding member of HuffPost Plus today.

This article originally appeared on HuffPost.