The Presidential Public Health Failure History Forgot

When health experts warned the president that a dangerous virus had emerged in the United States, he took swift action to protect the public.

No, not Donald Trump and the coronavirus, or Barack Obama and H1N1 influenza in 2009, or even Woodrow Wilson and the 1918 Spanish flu epidemic. The year was 1976, the president was Gerald Ford, and what followed illustrates the peril of trying to lead a country through a public health emergency.

On Feb. 4, 1976, Army Pvt. David Lewis, 19, collapsed and died after ignoring doctor’s orders and participating in a five-mile nighttime march at Fort Dix in New Jersey. Several weeks before, the Army had noticed many personnel at Fort Dix had contracted a respiratory illness, and brought in state and federal health officials to investigate.

Nine days after Lewis’ death, the federal Center for Disease Control (now the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) determined that influenza, specifically swine flu, had felled the young soldier. Although there had been isolated cases of swine flu in the United States since 1930, those people caught the virus from pigs. There had been no evidence of the virus passing from person to person.

As many as 500 people at Fort Dix had been exposed to the virus, including 14 who became ill. Lewis would prove to be the only person on Earth known to die from swine flu that year, and U.S. health authorities found no additional human-to-human cases of swine flu. The World Health Organization and other nations also did not detect additional transmissions.

But public health officials were terrified of the possibility of a viral pandemic, like the one that had killed 50 million people worldwide and 575,000 in the United States in 1918: the Spanish flu, which was also an H1N1 strain of influenza. The Spanish flu was highly contagious and deadly, and so much time had elapsed since 1918 that Americans younger than 50 had no natural immunity to the virus.

Inside the federal health care bureaucracy, top officials immediately started formulating plans for a major vaccination campaign. Within just a few weeks, Ford announced to the nation that his administration would buy enough vaccine doses to inoculate about 200 million people and oversee a national vaccination program. Eventually, the Democrat-led Congress endorsed the program with two new laws.

Nothing on that scale had ever been attempted, even for polio or smallpox. That well-intentioned response still stands as one of the worst public health failures in U.S. history.

The biggest difference between Ford’s failed swine flu program and Trump’s handling of the coronavirus pandemic is that Ford tried to do too much, while Trump has resisted stronger public health actions from the beginning.

Less than one-quarter of the population received the swine flu inoculation, and the vaccine itself was associated with a paralyzing immune disorder called Guillain-Barré syndrome, which caused more deaths than the virus it was supposed to prevent.

All medicines can cause side effects, including vaccines. Immunization programs like those for polio and smallpox are designed with that in mind, and with an aim toward protecting far more people than they harm. In the case of swine flu, there were only risks and no benefits, because an outbreak never occurred.

The Specter Of The Spanish Flu

Ford was only 5 years old during the Spanish flu pandemic, but the devastating outbreak loomed large in the cultural memory, as did the especially deadly pandemics of seasonal influenza during the winters of 1957-1958 and 1968-1969, when schemes to immunize the U.S. population failed.

The matter rapidly moved from the federal health agencies to the White House, driven by David Mathews, the secretary of health, education and welfare, Theodore Cooper, assistant secretary for health, and CDC Director David Sencer, each of whom favored an aggressive response. (In 1979, the Department of Health, Education and Welfare, also known as HEW, was split into the departments of Health and Human Services and Education.)

Six weeks after Lewis died at Fort Dix, Mathews wrote the White House Office of Management and Budget director, James Lynn, with dire warnings about a looming swine flu outbreak.

“There is evidence there will be a major flu epidemic this coming fall. The indication is that we will see a return of the 1918 flu virus that is the most virulent form of flu,” Mathews wrote on March 15. “In 1918, a half million people died. The projections are that this virus will kill one million Americans in 1976.”

One million deaths would amount to nearly 60 times the fatalities caused by the seasonal flu each year at the time.

This article draws from a book titled “The Swine Flu Affair: Decision-Making on a Slippery Disease,” published in 1977 by Richard Neustadt and Harvey Fineberg of Harvard University at the behest of the Department of Health, Education and Welfare. HuffPost also reviewed documents from the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library and Museum, contemporary reporting by The New York Times and The Washington Post, and an account of the campaign published in 2006 by Sencer and Donald Millar, who was the director of Ford’s immunization program.

Health officials led by the HEW’s Cooper provided Mathews and Ford with a range of options that included a national vaccination program, doing nothing at all and several alternatives in between. But the language in that March 13 memorandum from the HEW strongly suggested that the Ford administration do something big and fast.

“The situation is one of ‘go or no go.’ If extraordinary measures are to be undertaken, there is barely enough time to assure adequate vaccine production and to mobilize the nation’s health care delivery system,” the memo read. “Any extensive immunization program would have to be in full-scale operation by the beginning of September and should not last beyond the end of November 1976. A decision must be made now.”

After meeting with his health officials and outside scientists at the White House on March 22 and March 24, Ford made a fast decision to vaccinate the entire country.

“I think you ought to gamble on the side of caution. I would always rather be ahead of the curve than behind it,” Ford told Neustadt and Fineberg for their book.

Ford was facing a difficult reelection campaign. Former California Gov. Ronald Reagan was dogging him with a Republican primary challenge, and the looming general election against the Democratic former governor of Georgia, Jimmy Carter, was not far off. Swine flu didn’t end Ford’s presidency, but it didn’t help, either.

Decisiveness And Haste

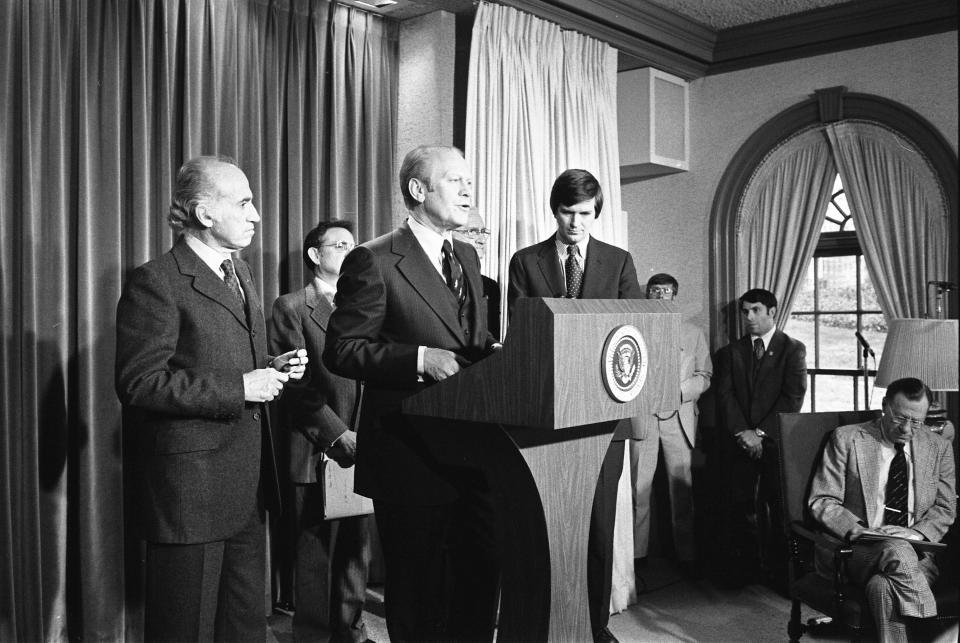

Ford held a press conference March 24 to announce the swine flu vaccination program. In addition to senior health officials and White House aides, Ford was flanked by two pioneers of the polio vaccine, Jonas Salk and Albert Sabin, who endorsed the plan. So did the American Medical Association and the Red Cross.

“One month ago, a strain of influenza sometimes known as swine flu was discovered and isolated among Army recruits at Fort Dix, New Jersey,” Ford told reporters that day. “The appearance of this strain has caused concern within the medical community, because this virus is very similar to one that caused a widespread and very deadly flu epidemic late in the First World War.”

“I have been advised that there is a very real possibility that unless we take effective counteractions, there could be an epidemic of this dangerous disease next fall and winter here in the United States,” he continued. “Let me state clearly at this time, no one knows exactly how serious this threat could be. Nevertheless, we cannot afford to take a chance with the health of our nation.”

From Ford’s perspective, this potential crisis and the complexity of responding to it presented a strong possibility of a no-win situation. Do nothing, or very little, and he risked the lives of Americans during what happened to be an election year. Attempt a major national initiative, and he risked failure. The chances that neither would happen and there would be no swine flu epidemic weren’t deeply considered.

“This administration can tolerate unnecessary health expenditures better than unnecessary death and illness,” Sencer wrote in a March 1976 memo.

Yet, there was no unnecessary death or illness except what the vaccine itself caused. Nine months after it was announced, the vaccination program died an unceremonious death and Ford’s presidency earned another black mark.

Dissent Unheeded

Ford believed he had unanimous consensus from health officials and outside scientific advisers to move forward with the vaccination program. But there were those in the CDC, HEW and the broader medical community who favored a more cautious approach but were ignored.

At the White House meeting that included Salk and Sabin, however, when Ford asked for dissenting views, the attendees remained silent. Moreover, Mathews and Cooper overhyped the comparisons to the Spanish flu outbreak, to the chagrin of Sencer and others. Even Sabin would later recant his support for the vaccination program in a New York Times op-ed, joining those who favored manufacturing and stockpiling the vaccine until evidence showed swine flu had spread.

Considering the messages Ford received from those whom he relied on and the potential for carnage on the scale of 1918, it’s no surprise the president wanted to take bold action.

But the problems with Ford’s program — and skepticism about it — had been evident almost from the beginning.

Drugmakers had just completed producing large supplies of the seasonal flu vaccine and would need to quickly ramp up production of a new vaccine. Some congressional Democrats, such as Rep. Henry Waxman (Calif.), viewed the plan dubiously. There was no infrastructure in place to manage a national immunization campaign, and the HEW would have to invent one in just months and coordinate planning with state and local health agencies.

The press also wasn’t convinced. After Ford concluded his March 24 press conference, Mathews, Cooper, Sencer, Salk and Sabin stayed behind to talk with reporters. Just minutes after hearing Ford’s presentation, reporters promptly posed questions that foreshadowed the immunization program’s ultimate failure.

Reporters asked about the capacity of the drug industry to make enough doses of the vaccine. They asked about harmful side effects. They asked about the federal government’s ability to quickly and capably implement Ford’s plan. They asked how much the vaccine would cost patients. And they asked about objections from medical experts to mass vaccinations.

Insurers Throw Up A Roadblock

The first sign of a problem that would ultimately delay the vaccination program for months came on April 8, when the pharmaceutical company Merck’s liability insurance company, Chubb, told the drugmaker its coverage would end if Merck participated in the vaccination program.

This issue worsened as the insurance industry refused to cover any of the vaccine manufacturers, which in turn told federal authorities they wouldn’t sell them vaccine without protection, even after Ford personally intervened. This delayed the vaccination program for months until Congress acceded to Ford’s demands for a law that would indemnify drugmakers and make the federal government responsible for any legal damages resulting from vaccinations.

In the meantime, the drug companies had begun manufacturing the vaccine. But even here, there was trouble. Parke-Davis (now part of Pfizer) produced 2 million vaccine doses for the wrong type of influenza, setting back production by a month or more. The drug company and the CDC blamed each other.

Those reporters at Ford’s March announcement and their sources outside the White House turned out to be prescient. An immunization program slated to begin in September slipped into October due to myriad problems, and it was over by December amid meager participation and growing evidence of a connection between the vaccine and Guillain-Barré syndrome.

The public also wasn’t on board. Although a Gallup poll released in August 1976 found that 93% of Americans knew about the swine flu vaccination program, only 53% had planned to get immunized. Scary public service announcements about the swine flu apparently hadn’t worked.

When the ill-fated vaccination program finally started on Oct. 1, it didn’t take long for more problems to come.

Three elderly people in Pittsburgh died on Oct. 11 after receiving the vaccine, leading city and county officials there to suspend all vaccinations for swine flu and seasonal flu. A handful of jurisdictions followed. Although authorities later determined the fatalities weren’t caused by the swine flu vaccine, public trepidation about the immunization program ― and media scrutiny of it ― grew as more than 40 people died after being vaccinated that month.

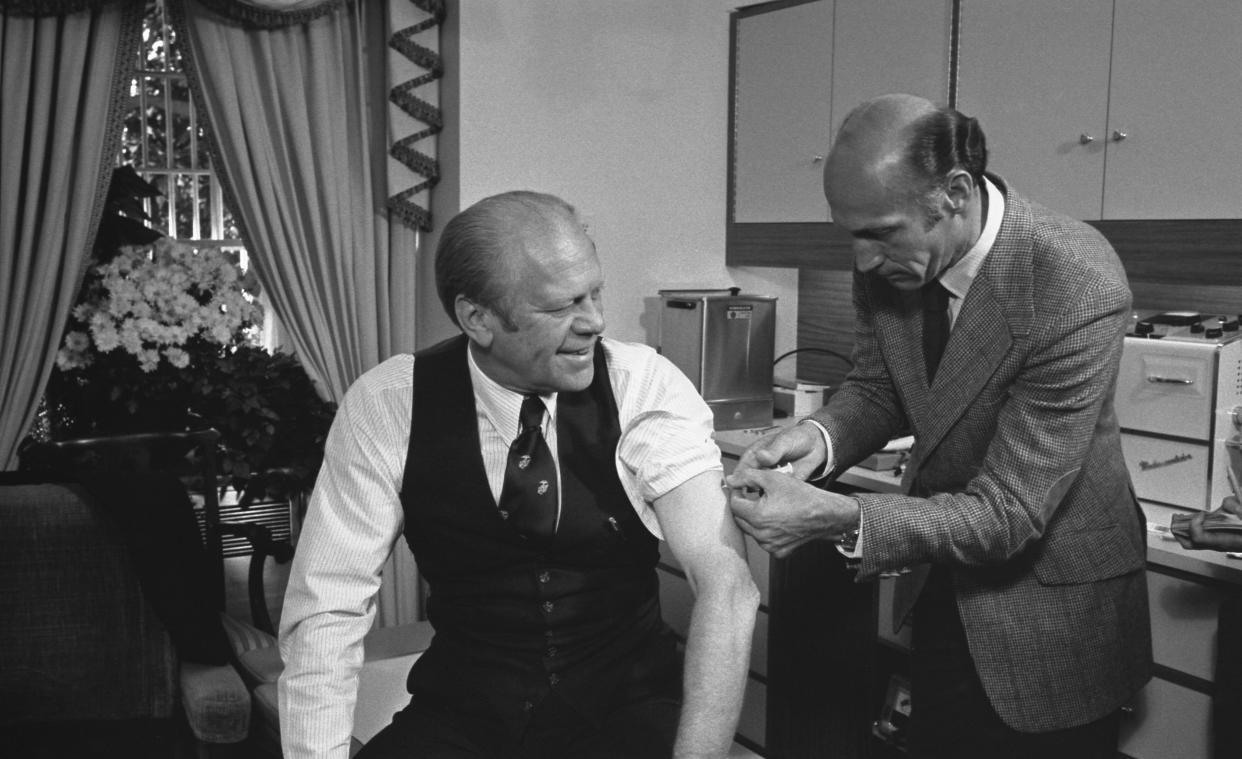

To quell worries, Ford and his family were inoculated for swine flu on Oct. 14, an event that was televised and photographed. Although Carter didn’t publicly criticize Ford’s immunization efforts, he pointedly declined to be vaccinated.

The immunization program was finally underway. But Carter narrowly defeated Ford on Election Day, leaving swine flu as Ford’s legacy.

Severe Side Effects

The next month, Minnesota health officials began to notice another disturbing trend when they recorded the first known instance of Guillain-Barré in a vaccinated patient. Minnesota had been especially aggressive in carrying out immunizations and had vaccinated nearly two-thirds of adults in the state. The number of known Guillain-Barré cases grew to 54 by Dec. 14, when the CDC published findings from 10 states.

Two days later, Mathews and other federal officials advised Ford to suspend swine flu vaccinations, and the president agreed. In addition, the snafu about vaccine safety also led the Ford administration to halt all flu inoculations, and they didn’t resume until the early days of the Carter administration. The CDC, New York City, New Jersey and Connecticut all reported a decline in other immunizations during the swine flu campaign and attributed that to resources being diverted from efforts to prevent other infectious diseases, like measles.

Ten months, hundreds of millions of dollars and a single death later, the National Influenza Immunization Program was over and could only be viewed as a ”fiasco,” as New York Times editorial writer Harry Schwartz put it on Dec. 21.

In retrospect, as Richard Krause, a senior National Institutes of Health official under Ford, Carter and Reagan, wrote in 2006: “The Fort Dix outbreak was a false alarm, and the American public and much of the scientific community accused us of overreacting. As someone noted, 1976 was the first time we had been blamed for an epidemic that did not take place.”

The parallels between the present-day coronavirus pandemic and Ford’s misbegotten swine flu campaign are limited. Though it proved unnecessary and even misguided, the Ford administration was trying to prevent a major outbreak before it happened. The coronavirus was already in the United States before the Trump administration took any action to halt its spread, and its management of the pandemic may well be recalled by history even more unfavorably than Ford’s.

In addition, the H1N1 flu ― including the Spanish flu, the swine flu and the flu that hit the U.S. in 2009 ― was well-understood in 1976, unlike the strain of coronavirus now spreading around the globe. Likewise, drug companies had the capability of developing influenza vaccines after decades of preparation for seasonal flu outbreaks.

The most significant connection between the 1976 outbreak-that-wasn’t and the 2020 coronavirus pandemic is arguably politics and public opinion. Ford tried to do too much, and he paid for it. Trump hasn’t tried to do enough, and people are dying.

Johnny Carson, the host of “The Tonight Show” and a major cultural force in late 20th-century American culture, provided perhaps the best epitaph for Ford’s gambit.

Three weeks after the the swine flu vaccination efforts were discontinued and just 13 days before the end of Ford’s presidency, Carson appeared in a sketch as his long-running clairvoyant character, Carnac the Magnificent. As Carnac, Carson would hold up sealed envelopes to his forehead and “guess” the answer to questions written on slips of paper within.

On the night of Jan. 7, 1977, Carson guessed, “the swine flu vaccine.” The question? “Name a cure for which there is no known disease.”

A HuffPost Guide To Coronavirus

Stay up to date with our live blog as we cover the COVID-19 pandemic

What happens if we end social distancing too soon?

What you need to know about face masks right now

How long are asymptomatic carriers contagious?

Lost your job due to coronavirus? Here’s what you need to know.

Everything you need to know about coronavirus and grief

Parenting during the coronavirus crisis?

What coronavirus questions are on your mind right now? We want to help you find answers.

Everyone deserves accurate information about COVID-19. Support journalism without a paywall — and keep it free for everyone — by becoming a HuffPost member today.

Love HuffPost? Become a founding member of HuffPost Plus today.

Also on HuffPost

This article originally appeared on HuffPost.