Donald Trump’s Race Speech In Tulsa Will Be Just Another Sop To His White Supporters

President Donald Trump is going to Tulsa, Oklahoma, the site of a 1921 racist massacre triggered by white resentment, on June 19, the Juneteenth holiday celebrating the Black emancipation from slavery and the continued struggle for freedom. He’s planning a rally while Americans join in widespread anti-racism protests, which he opposes. And he’s going so he can talk up his record on race to his largely white voter base.

The rally next Friday will be Trump’s first since suspending major campaign events due to the coronavirus pandemic and the first since global protests began after the police killing of George Floyd, a Black man, in Minnesota.

White House press secretary Kayleigh McEnany said Thursday that he’s holding the rally on Juneteenth because “it’s a meaningful day to him, and it’s a day where [he] wants to share some of the progress that’s been made as we look forward and more that needs to be done.”

The rally, in other words, will be a place for the white president to talk to a mostly white crowd about all of the good he’s done for Black people. If it follows Trump’s trends in speaking about race, he will give a self-congratulating speech about how he has, as he’s fond of saying, “done more for the Black community than any president since Abraham Lincoln.” There will be talk of the Black unemployment rate, a talking point now made moot; his urban Opportunity Zones, which have so far enriched only white billionaires; criminal justice reform, which came as he rolled back Obama administration police reforms; and he’ll claim that he “saved” historically black colleges and universities.

It is “almost blasphemous,” CeLillianne Green, a historian and poet, told The Washington Post.

And, “more than a slap in the face to African Americans, it is overt racism from the highest office in the land,” Rep. Al Green (D-Texas) tweeted about Trump’s hijacking of the symbols of Tulsa and Juneteenth.

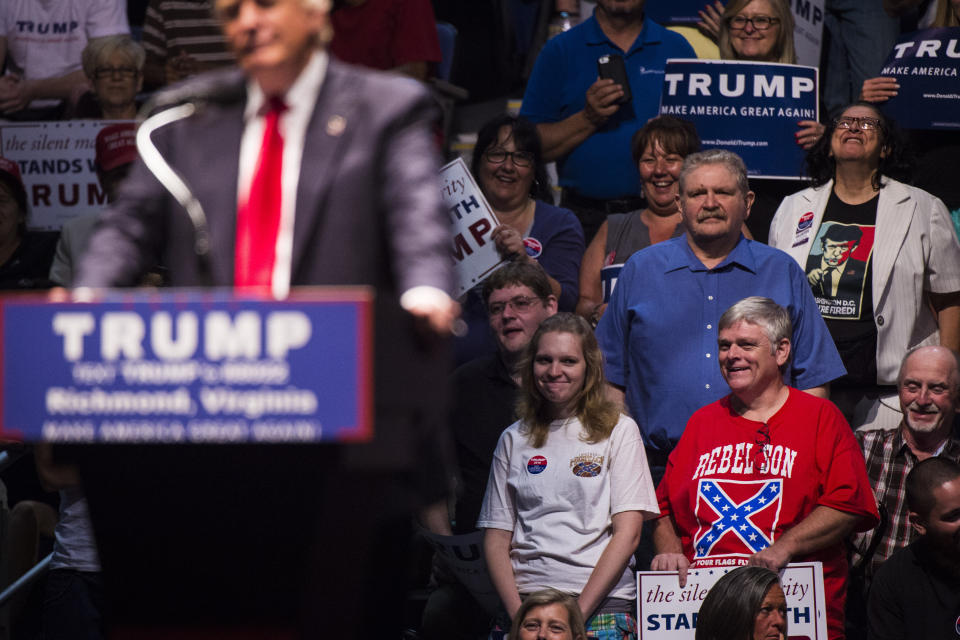

Trump’s campaign intends to use these symbols of Black oppression and Black freedom to sell his reelection despite the fact that he’s the most openly racist U.S. president in modern history. He will give this speech not from behind his desk at the Oval Office, where he would be presented as president of all Americans, but to his fervent and mostly white supporters at one of his infamous rallies, which have at times displayed racist violence that he encouraged.

His audience is not the nation at large, let alone Black Americans, but the white pro-Trump faithful. Trump’s political success has been buoyed by a racist white backlash based in resentment of the election of the first Black president, Barack Obama, and the country’s changing racial demographics. Similar resentments of Black gains led whites to burn Tulsa’s Greenwood District 99 years ago.

The Greenwood Massacre

On May 31, Tulsa commemorated the 99th anniversary of the Greenwood Massacre. The massacre, formerly known as the Tulsa Race Riots, occurred when a white mob, aided by police officers, killed up to 300 people as they destroyed a vital Black business district.

The Black business district in the segregated neighborhood began with the opening of a grocery store in 1905. By the late 1910s, the district had flourished with dozens of businesses, churches, a public library, a movie theater and a three-story hotel. It became known as Black Wall Street.

In 1919, 380,000 Black American soldiers came home from World War I. They were determined that their sacrifice for their country should be rewarded with freedom at home.

“We return,” W.E.B. DuBois wrote about Black veterans in 1919. “We return from fighting. We return fighting.”

White America met them with closed fists. Even before Black veterans returned home, racist politicians were warning that their patriotism was a threat to white supremacy.

“Impress the negro with the fact that he is defending the flag, inflate his untutored soul with military airs, teach him that it is his duty to keep the emblem of the Nation, it is but a short step to the conclusion that his political rights must be respected,” Sen. James Vardaman, a Mississippi Democrat, said in 1917.

In the Red Summer of 1919, white mobs rioted in Black neighborhoods in Chicago; Houston; Omaha, Nebraska; Charleston, South Carolina; and Washington, D.C. In Washington, the first victim was a 22-year-old Black veteran. In other cities, Black veterans defended their neighborhoods from the racist mobs. In the South, Black veterans were assaulted simply for appearing in uniform in public, and at least 13 were lynched.

These passions did not recede after 1919, particularly in Tulsa. White resentment boiled as the successful Greenwood District grew, until it ran up against white Tulsa’s boundaries. Those resentments exploded after a downtown Tulsa clerk accused a Black teenager, who had touched the arm of a white elevator attendant, of rape.

The teen was arrested, and an armed white mob came to haul him out of jail and murder him. But they were met by a Black mob from Greenwood, including armed WWI veterans, who had come to protect the teenager. A fight happened after a white man challenged one Black veteran’s right to carry a gun. Someone fired a weapon, and within minutes 20 were dead on both sides.

With the blessings of the police, thousands of whites descended on Greenwood and killed hundreds of Black people, looted stores and burned the neighborhood to the ground. They were aided by police-approved airplanes that dropped bombs. Nearly every commercial property was destroyed, and 9,000 people were left homeless. The fire department did not respond. The police pressed no charges. Political and religious leaders blamed the Black residents. An investigation into the massacre was not conducted until 2001.

It was yet another example of white America seeing Black America’s success as an existential threat and then sweeping it into the dustbin of history.

Juneteenth

President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation on Jan. 1, 1863, turned the Civil War into a battle for the liberation of enslaved people in the South. But for most enslaved Black people, liberation did not arrive until Union troops did. In Texas, that date arrived months after the war’s end and Lincoln’s assassination on June 19, 1865, when Gen. Gordon Granger informed a gathering of slaves they had been freed when he read Lincoln’s proclamation.

Celebrations of liberation proliferated in Black communities throughout the South after the Civil War. These Emancipation Days were usually held on the dates that the local Black population was emancipated, like April 16 in Washington, D.C., or on Jan. 1 to commemorate Lincoln’s proclamation. Naturally, Texans celebrated Emancipation Day on June 19. The holiday came to be called Juneteenth.

Emancipation Day has been a moment to celebrate freedom and to reflect on slavery. Many celebrations petered out or were suppressed as the Jim Crow era of white supremacist authoritarianism descended on the South at the turn of the 20th century. But Juneteenth spread, thanks in part to the Great Migration of Blacks escaping the repression in the South for the promise of the North and West. The date is currently either a holiday or a day of commemoration in 47 states, but the federal government does not recognize any day as a national holiday to celebrate emancipation.

“The people from Texas took Juneteenth Day to Los Angeles, Oakland, Seattle, and other places they went,” Isabel Wilkerson wrote in “The Warmth of Other Suns.” “Even now, with barbecues and red soda pop, they celebrate June 19, 1865, the day Union soldiers rode into Galveston, announced that the Civil War was over, and released the quarter-million slaves in Texas who, not knowing they had been freed, had toiled for two and a half years after the Emancipation Proclamation.”

Trump’s Racism

Like all of Trump’s talk about race in America, his Tulsa address is meant for the consumption of his base of white supporters. He is incapable of striking any other tone when he talks about race in America because he has already laid his cards on the table. He not only began his political career with a racist smear of the first Black president, but he also has solidified his opposition to the Black struggle for further liberation, symbolically represented by the Juneteenth celebration, by demagoguing Black Lives Matter protests with his hateful attacks.

“The first time I heard [Black Lives Matter], I said, ‘You have to be kidding,’” Trump said in 2016. “I think it’s a very, very, very divisive term. There’s no question about it.”

“He’s wrong,” Trump said after former Secretary of State Colin Powell, a Republican, talked about his support for Black Lives Matter protests in 2015. “He’s totally wrong. It’s ‘All lives matter,’ and that should be the theme of this country, frankly, or one of the themes. So he’s obviously catering to somebody. I don’t know who he’s catering to.”

The 2016 Republican National Convention gave an entire night the theme of “Make America Safe Again” that featured speakers denouncing Black Lives Matter and praising police ― to raucous applause.

Multiple Black Lives Matter protesters who disrupted Trump’s rallies were assaulted by his supporters. “Maybe he should have been roughed up because it was absolutely disgusting what he was doing,” Trump said about one Black Lives Matter protester who was assaulted at a rally.

At another rally, Trump urged his supporters to physically eject three protesters who had chanted Black Lives Matter slogans. “Get out!” he bellowed. “Get them out!” The three protesters, a man and two women, were then pushed and punched by his supporters. One of those supporters was a “Make America Great Again”-hat-wearing Matthew Heimbach, a white supremacist once touted as the next David Duke.

“White Americans are getting fed up and they’re learning that they must either push back or be pushed down,” Heimbach, who would later plead guilty to assault from the incident, wrote in a blog post afterward.

Heimbach would later help organize and attend the Aug. 12, 2017, “Unite the Right” white supremacist rally to protect a statue of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee in Charlottesville, Virginia. The murder of Heather Heyer by one of the rally attendees resulted in Trump attempting to give his first talk on race relations in America, in which he declared that some of the white supremacists and neo-Nazis there were “fine people.”

Trump also defended the stated cause of the white supremacists: not removing the statue of Lee. He has since become the leading proponent of maintaining and venerating Confederate symbology throughout the United States, including on military bases. Republican senators agreed Wednesday night to an amendment offered by Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) to rename military bases that honor Confederate generals over the next three years. Trump tweeted his opposition Thursday afternoon.

“THOSE THAT DENY THEIR HISTORY ARE DOOMED TO REPEAT IT!” Trump tweeted Thursday in response to efforts to remove Confederate symbols across the country.

He’s also spent the past few weeks praising police and suppressing protests against police brutality after Floyd’s death. While he condemned the police officer who killed Floyd by kneeling on his neck for nearly nine minutes, Trump has said that there is only a small proportion of “bad apples” within police forces.

These acts, but not these alone, will make it impossible for any message of racial reconciliation from Trump to reach Black America, and an increasing part of white America, without it being viewed as anything more than the condescension it is.

Trump venerates a certain strain of white history, one that buries the history of Greenwood and does not celebrate emancipation, unless suddenly politically convenient. But Black Americans remember their history, too.

“Negro American consciousness is not a product (as so often seems true of so many American groups) of a will to historical forgetfulness,” Ralph Ellison wrote in 1963. “It is a product of our memory, sustained and constantly reinforced by events, by our watchful waiting, and by our hopeful suspension of final judgment as to the meaning of our grievances.”

Love HuffPost? Become a founding member of HuffPost Plus today.

Related...

With Trump MIA, Senate Republicans Go It Alone On Police Reform Efforts

Trevor Noah Shreds Trump's '99%' Of Police Are 'Great People' Line

Donald Trump Is Acting Like The Coronavirus Is Gone. It Isn’t.

This article originally appeared on HuffPost.