DOJ charges against Unforgiven show reach of white supremacist gangs in prisons – and on the streets

Outside the public spotlight trained on the Oath Keepers and Proud Boys, the right-wing extremist groups most associated with the Capitol riots, federal authorities are striving to rein in what many experts say is a far more violent and secretive threat – white supremacist prison gangs operating inside the wire and out on the streets.

The Justice Department last week unsealed indictments against 16 members of Unforgiven, Florida’s largest white supremacist gang, charging them with engaging in a criminal racketeering enterprise that involved murder, kidnapping and assault with a deadly weapon. Last October, five indictments in three different states named 24 defendants, including alleged Aryan Circle gang members and associates on similar charges.

These and other recent cases built by federal and state authorities offer an unusually detailed glimpse of the internal machinations of some of the most well-organized and murderous hate groups that have been active in the United States over the past half-century.

Unlike many right-wing extremist groups that operate openly, white supremacist prison gangs intentionally keep as low a public profile as possible so as not to attract attention to their illicit moneymaking enterprises, which authorities say include drug and weapons trafficking, extortion and murder for hire.

But prosecutors allege that groups like Unforgiven, Aryan Brotherhood, Aryan Circle, Nazi Low Riders and Public Enemy No. 1 are a menace to society because of their penchant for explosive and often deadly racial violence, often done in “pursuit of business and political leadership.”

Unforgiven, for instance, continually seeks to expand its power, territory and reputation – in and out of prison – by systematically recruiting members and indoctrinating them in a vicious form of white supremacist ideology that permeates everything they do, court documents show. It requires its members to study and propagate “Aryan philosophy,” to pay dues and to perform violent acts to join and remain in the group, prosecutors said.

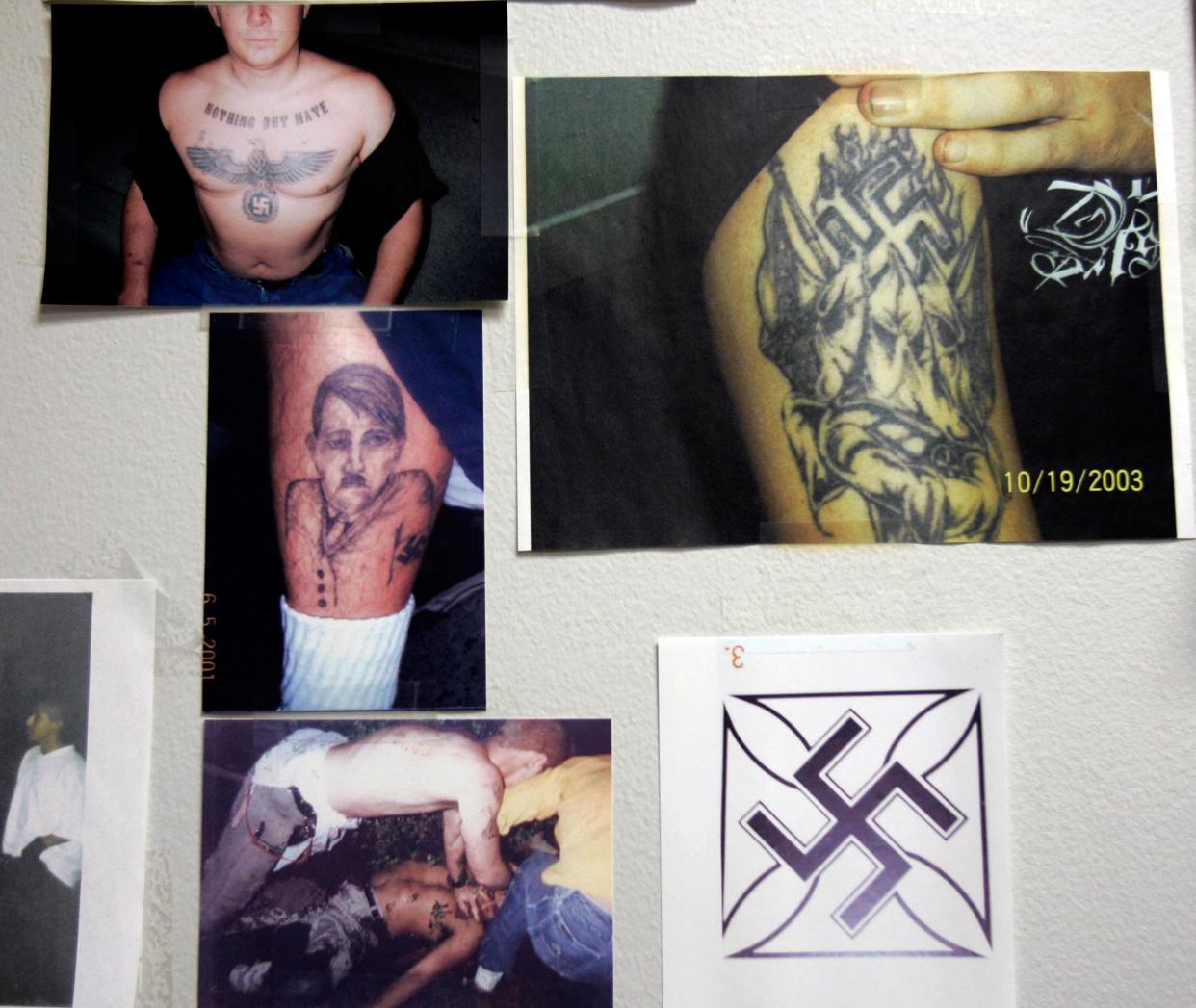

Tattoos of swastikas, Iron Crosses, SS bolts and other Nazi symbols, they allege, are also required – and so is attendance at meetings known as “church.”

Members must enrich the broader enterprise through distribution of weapons, narcotics and contraband – and by creating a united front to “resist and rebel” against the perceived “constant and almost brutal victimization of Whites” in the Florida penal system, according to the indictment.

Three of Unforgiven’s members – George “Shrek” Andrews, Joshua “Chain Gang” Williamson and Brandon “Scumbag” Welch – face up to 20 years in prison if convicted.

“Prison gangs have been one of the least covered but most violent aspects of organized white supremacy, and they have been growing at various intervals in recent decades, even in times when outside hate groups were experiencing declines,” said Brian Levin, one of the foremost experts on white supremacist prison gangs who has advised federal authorities and Congress on how to combat them.

When toxic ideology meets political and cultural upheaval

Evidence of an upswing in political violence by members of white supremacist prison gangs is anecdotal, experts and current and former federal law enforcement officials acknowledge. But they say there are troubling indications of it, and that the conditions are ripe.

While the white supremacist prison gangs themselves haven’t changed much over time, society certainly has. Now, ex-convicts who have been radicalized – or further emboldened – by the white power ideologies of their prison colleagues are re-entering society at one of the most turbulent and politically combustible times in recent memory. And that has authorities bracing for trouble.

“Traditionally, we haven't seen prison gangs openly participating in these kinds of violent political riots,” said Levin, director of the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism at California State University – San Bernardino. “But these elastic pools of grievance are now ensnaring everybody from anti-vaxxers to Stop the Stealers to prison gangsters who don't have to adhere to a rigid ideological set of talking points. Their perceived enemies are now the same: elitist authority.”

REPORT: White supremacist propaganda hit all-time high in 2020

One of the Unforgiven defendants, David Howell, used a deadly weapon to assault protesters at a "Peace Walk for Black Lives" event in June 2020 in order to gain entrance to the group and to maintain and increase his position in it, prosecutors said in the indictment unsealed July 15.

And Michael Curzio, an ex-convict Unforgiven member who was not included in the indictment, pleaded guilty earlier this month to playing a role in the Jan. 6 siege of the U.S. Capitol. He had been out of prison for less then two years after serving eight for attempted manslaughter, when he was part of a crowd near the door to the House atrium that refused orders to leave. Authorities who photographed him after his arrest documented numerous Nazi swastika tattoos.

Some experts say a flurry of recent prosecutions is somewhat coincidental, and merely an extension of long-running investigations that stretch back years or even decades.

One current federal law enforcement agent who specializes in white supremacist prison gangs said authorities are focusing more aggressively on the issue of right-wing extremism in the wake of the attempted insurrection this past January and other high-profile displays of political violence dating back to the “Unite the Right” rally Charlottesville, Va. in 2017.

“There are still members out there in these gangs. They're still committing crimes. They're still committing murders. I mean, that's just part of their day-to-day business, right?” the federal law enforcement agent said, speaking on the condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to discuss ongoing enforcement matters.

“It's not as pervasive as it was in the early 2000s or even in the 1990s,” he added, “but because we're all hypersensitive about [right-wing extremism], I think they are gaining more attention.”

But Mark Pitcavage, senior research fellow with the Anti-Defamation League’s Center on Extremism, said white supremacist prison gang violence also appears to be on the upswing, in part, because of a recent move by some states to eliminate the use of solitary confinement and other administrative efforts to isolate prison gang leaders and other particularly dangerous inmates.

“At one point, the Aryan Brotherhood leadership was pretty tightly controlled [by prison officials], and it was very hard for them to get messages out or hit orders out or anything like that,” said Pitcavage, whose reports on white supremacist prison gangs are used in the training of corrections officials.

“But now, a lot of those people are out in the yard again, and especially some of the assassin-level people," Pitcavage said. “As a result of that, we've seen Brotherhood-related violence go up in California.”

Pitcavage said that violence is likely to spill out onto the streets, where white, Black and Hispanic prison gangs battle for control of criminal activity.

Traditionally, white supremacist prison gangs, whose total members number in the tens of thousands, have focused most of their violence on rival gangs, suspected informants and anyone who gets in the way of their lucrative criminal enterprises. But they have not hesitated to use targeted violence – including assassinations of judges and prosecutors and pipe-bomb explosions – to make a statement or get what they want.

White supremacist prison gang members and ex-convicts also have engaged in dozens of heinous and indiscriminate acts of racial violence against minorities, Jews and other “non-Whites” whom they believe are inferior, often in order to gain acceptance into the groups or to rise within their hierarchy.

One challenge for authorities is that prison gangs, including others formed by Black and Hispanic inmates, are almost impossible to eliminate.

When members of more conventional extremist groups get arrested for violent acts in their communities, they are prosecuted and, if convicted, sent to prison.

“If the group is small, that probably ends the group right there,” Pitcavage said. “But if you put white supremacist prison gang members behind bars, they just continue their activities. They can exist and operate behind bars almost as easily as on the streets.”

That’s one of the reasons federal authorities have ramped up their prosecutions of white supremacist prison gangs in recent years, said Brian Benczkowski, a veteran Justice Department official who served as Assistant Attorney General for DOJ’s Criminal Division in the Trump administration.

“There is no doubt that domestic extremism is and should be a top priority for federal law enforcement,” Benczkowski said. “But it is important to understand that the Justice Department aggressively pursues regional, national, and transnational street and prison gangs – be they MS-13, the Gangster Disciples or the New Aryan Empire – not because of any ideology, but because these groups pose a significant threat to public safety by engaging in dangerous criminal activity and extreme violence.”

Racial divisions, recruitment and risk

Since at least the 1980s, prison gangs have formed on racial lines as a way to build protection for inmates. Unlike domestic extremist groups on the outside, ideology is not always the reason for becoming involved.

When an inmate from a white supremacist prison gang is released, there is a chance that they have become radicalized to that ideology.

“But that is not always certain,” said former FBI domestic terrorism agent Tom O’Connor. “If an ideologically-driven violent actor becomes an inmate, it is for sure they will connect with like-minded individuals on the inside,” as well as on the outside on their release from prison.

“The [federal] Bureau of Prisons and the FBI work diligently to identify gang activity on the inside, as many acts of violence are based on these racial divisions,” O’Connor said.

Once these inmates are released from prison, he said, they are often at heightened risk of joining other white supremacist or militia organizations.

“Those who are prone to violence are prime targets for recruitment to fringe groups looking for people to carry out acts,” said O’Connor, who was also head of the FBI Agents Association until his retirement in 2019. “Many people leaving the prison system without family or networks awaiting them will be looking for acceptance. They may well find it in outside extremist ideologies.”

Radicalized politics, conspiracies

Authorities are also concerned that some of these gang members are coming out of prison already steeped in the conspiracy theories that have become rampant during the 2020 election and its contested aftermath.

“Inmates on most levels have access to social media and online interaction while incarcerated,” O’Connor said. “The likelihood of some individuals being swept up in conspiracy and anti-government rhetoric is real.”

Curzio, for his part, was arrested a week after the Capitol riot and held in custody pending trial due to his prior felony conviction, which stemmed from his shooting his ex-girlfriend's boyfriend during a fight at her home.

In their effort to keep Curzio locked up, authorities wrote in court documents that he was a member of Unforgiven while behind bars in Florida and that he had tattoos with Nazi imagery at the time of his arrest.

Earlier this month, Curzio pleaded guilty to joining the mob that stormed the U.S. Capitol and was released from jail because he had already spent six months in custody.

In his defense, Curzio claimed he was essentially an innocent bystander in the riot and said his presence there had nothing to do with his affiliation with Unforgiven.

Curzio, 35, joined Unforgiven in order to survive in prison after being attacked by other inmates, his defense lawyer wrote in court documents arguing for his pre-trial release. The attorney, A. Eduardo Balarezo, has said in interviews that Curzio is no longer associated with the prison gang but lacks the funds to remove the tattoos.

“It is notable that on January 6, 2021, Mr. Curzio did not go to the Capitol in the company of any gang members; he did not wear any gang colors; he did not give a Nazi salute; he did not have any posters with Nazi insignias. In short, his presence at the Capitol had nothing to do with his prior gang affiliation,” Balarezo wrote in court documents file in April.

Levin said it’s not unusual for members to join a prison gang because they were forced to, or to gain protection from rival gangs. But he said Curzio’s case, and that of Unforgiven, speak to broader concerns that authorities have about the evolving nature of the threat.

"While his participation in the insurrection does not directly implicate the Unforgiven Nazi gang in an organized way, this is yet another example of how for many far right assailants, the radicalizing narrative of violent, leaderless resistance attacks against a list of perceived enemies, like the government, is having a resurgence,” said Levin.

Levin also noted that unlike other Aryan prison gangs that exist first and foremost as criminal enterprises, Unforgiven has established its own “political wing.”

To Levin, it is further proof of the blurring of lines between prison gangs and other right-wing extremist organizations.

“This is something we see more often with terrorist groups like the IRA and Hezbollah,” when they are trying to become more a part of the political mainstream in order to attract more support, legitimacy and funding, Levin said. “It just shows the gravitational pull of the mainstreaming of violent right-wing politics, and how it is now ensnaring a real mottled assortment of folks that range from upper-class business people to members of white supremacist prison gangs."

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: DOJ Unforgiven charges show reach of white supremacist gangs in prison