Why 5 Freshman Democrats Sided With Trump And Saudi Arabia On A Key Yemen Vote

When the House of Representatives voted earlier this month to ban U.S. assistance for Saudi Arabia’s military intervention in Yemen, the Democratic caucus was united ― except for five new members, who surprised their colleagues by joining most Republicans to oppose the measure.

Reps. Abigail Spanberger (D-Va.), Chrissy Houlahan (D-Pa.), Jason Crow (D-Colo.), Mikie Sherrill (D-N.J.) and Elissa Slotkin (D-Mich.) all have national security experience, having served in either the military or the intelligence community. Their vote effectively meant they would have granted the Trump administration leeway to keep supporting the Saudis, the United Arab Emirates and others in a campaign against a Yemeni rebel group supported by Iran.

In April, Congress had passed a similar proposal, forcing President Donald Trump into a rare and embarrassing veto to protect a war effort accused of scores of war crimes. It was a testament to the success of a yearslong crusade by a handful of committed Democrats and Republicans, along with outside peace groups. Ultimately, their campaign garnered universal endorsement from Democratic leadership, despite reluctance from figures like House Majority Leader Steny Hoyer (D-Md.) to squabble over an Obama-era policy or seem weak on Iran.

The campaigners want to finish the job now by pinning a ban on U.S. support to a must-pass defense spending bill.

The five lawmakers’ decision to split with them had limited impact: The bill passed the Democratic-controlled House by a vote of 240-185. Advocates will next fight to keep the amendment in the final legislation to be negotiated with the Republican-controlled Senate and sent to Trump.

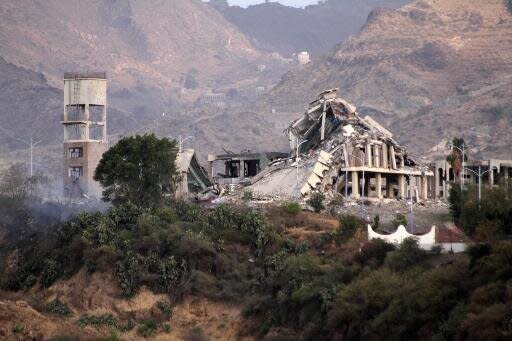

There’s a stark moral dimension, nonetheless, in choosing to bless U.S. aid for an intervention fueling the world’s worst humanitarian crisis ― one that’s poised to worsen ― when it’s clear that sustained pressure from Capitol Hill is key to forcing limits on the policy. Last year Trump responded to congressional uproar over the Saudis’ conduct in Yemen and their role in the murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi by ending American aerial refueling of the Saudi-led alliance’s bombing runs. Yet there’s nothing stopping him from reversing that decision ― and so far this year, he’s already deployed unprecedented measures to squeeze down on Iran, fast-tracking weapons shipments to the Saudis and the UAE.

The move by the five lawmakers also matters for the evolution of the Democratic Party. They’re all seen as rising stars: They flipped GOP seats, scored powerful committee assignments and won glowing media attention. Their views will affect how the party develops, especially if the 2020 election gives Democrats greater influence over global affairs ― and so will their willingness to clash with progressives who want new restraints on the war-making authorities of the executive branch and a more dovish foreign policy generally.

Some Yemeni Americans and advocacy groups are now calling the lawmakers the “Famine Five,” a reference to how the U.S.-backed war has helped create mass starvation in Yemen and a term that activists used last year for other Democrats who joined then-Speaker Paul Ryan (R-Wis.) to block a House vote on the matter.

The five freshman lawmakers say they generally object to American assistance to the Saudi-led coalition. All five backed the earlier bill vetoed by Trump that directed an end to the policy.

Houlahan “wants to see an end to this conflict and she’s voted repeatedly on that basis,” a senior aide to the congresswoman told HuffPost. Slotkin and Crow have both supported other proposals to bar material support to Riyadh, aides to both told HuffPost.

Their disagreement with their fellow Democrats arose over one aspect of the most recent legislation: language that says Washington cannot share intelligence with the Saudi-led coalition for purposes of strikes against the Yemeni rebel militia, known as the Houthis.

That intelligence can mitigate civilian casualties and protect ground forces, aides to Crow and Houlahan said.

“Nothing in the law should prohibit us from trying to be helpful,” the Houlahan aide said, noting the bill would, for instance, prevent the U.S. from sharing a list of facilities not to strike.

The use of American intelligence could also be important if the Houthis threatened the U.S., the aide continued.

A Slotkin aide also cited concern over limiting U.S. capacity in the face of future crises. The congresswoman “knows from personal experience that the United States, in rare instances, needs to share intelligence to support U.S. national security interests, to allow for the safety and security of international maritime traffic in congested areas such as the Bab-el-Mandeb,” a strategic strait off the Yemeni coast, the aide wrote.

There’s plenty within that logic to worry critics of the five and skeptics of the traditional U.S. approach to foreign policy.

Though the Houthis have launched attacks into Saudi Arabia, most of Congress and the U.S. foreign policy establishment have been careful not to speak of the rebels as potential targets of U.S. military action, even as they have noted the rebels’ excesses like using child soldiers and torturing political opponents.

The fear is that Washington will only gain an unnecessary enemy if it begins to demonize one set of players in a complex civil war who, as all sides recognize, will retain some influence in a future peace. Keeping the door open for the executive branch to decide it wants to share information to target the Houthis boosts the risk of confrontation with the rebels, particularly as the Trump administration speaks of the militia as part of an Iran-backed axis of evil. Protecting the option also maintains a broader congressional deference to executive decisionmaking that anti-war groups have challenged for decades, arguing that the lack of tighter limits and congressional debate on where and why the president can send bombs and troops is what’s gotten America embroiled in dozens of conflicts.

The idea that American intelligence saves lives has long been a favored Pentagon talking point. But policymakers from both parties know that even as they’ve received U.S. intelligence since 2015, the Saudis and their partners have bombed Yemeni schoolchildren, markets, hospitals and weddings.

“If anything, [intelligence sharing] just involves the United States in the targeting process,” said Kate Kizer of the group Win Without War, noting that might make Americans culpable in violations of international human rights law.

Slotkin, one of the freshman five, shares some of those misgivings.

“During [her] time at the Pentagon, the U.S. government pulled back support to Saudi Arabia, because it became clear that despite U.S.-Saudi intelligence sharing, significant civilian casualties were still occurring in Yemen,” her aide noted, an apparent reference to President Barack Obama’s decision to halt a major shipment of bombs to Saudi Arabia at the end of 2016. (Obama continued refueling for Saudi-led coalition planes dropping bombs and some intelligence sharing; Trump reversed his move on the weapons.)

A congressional staffer involved in Yemen policy said the members were sharing a “tired old argument.”

“We know that the only way to end all civilian casualties is to end all support for the war,” the aide said. “The U.S. and the Saudis were intelligence partners before this war, so there’s no reason to think that we end this war and then that would be the end of U.S. and Saudi intelligence cooperation.”

The chief Yemen-based threats to the U.S. are Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, a group that’s taken advantage of the chaos of the civil war, and the country’s nascent branch of the Islamic State. Washington was fighting those organizations before it signed on to the Saudi-led alliance’s actions, and neighboring countries are worried about terrorism from those groups regardless of U.S. participation in the intervention.

Still, a prohibition on one form of intelligence sharing could bleed into the counter-terror fight and that could be a problem at some critical moment. The argument from the five lawmakers is that the authors of the Yemen amendment should have considered such a situation.

Still, a prohibition on one form of intelligence sharing could conceivably hamper the counter-terror fight, should some unexpected but critical situation arise in which passing on data about the Houthis helps with targeting militants that the U.S. is fighting. The argument from the five lawmakers is that the authors of the Yemen amendment should have considered such a development.

The previous Yemen legislation that the lawmakers did support included an amendment from Rep. Ken Buck (R-Colo.) that explicitly said the end to American assistance for the Saudi-led coalition would not take away the president’s authority to share intelligence when he or she saw fit.

Yet Buck supported the current Yemen bill ― and so did House Intelligence Committee Chairman Adam Schiff (D-Calif.) and all the other Democrats working on the panel.

Spokespeople for Spanberger and Sherrill did not respond to multiple requests for comment for this story.

Top Democrats aren’t likely to pick a fight with the junior lawmakers over this one instance of disagreement. A spokeswoman for Rep. Ro Khanna (D-Calif.), who has led the House effort to remove the U.S. from the war, said he acknowledges each lawmaker’s right to vote based on personal beliefs and constituents’ views.

“Rep. Khanna has a difference of opinion on this issue and will continue to try to make the case for his perspective within the caucus,” Heather Purcell wrote in an email.

For advocates in touch with grassroots activists, though, it’s a worrying sign. “I think given all the abuses by this president to shield Saudi Arabia and the UAE … Democratic members at the very least would be united with the rest of their caucus as well as their constituents who want to end the U.S. role in this war,” Kizer said.

And it’s a potential canary in the coal mine, warning of Democratic Party fractures across all areas of policy. The five lawmakers are all part of a centrist coalition in the House that’s wary of more liberal colleagues like Reps. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.), and three of them ― Crow, Sherrill and Houlahan ― are members of a bipartisan caucus linked with a political action committee that is supporting a Republican challenger to another freshman Democrat.

Other national security subjects have prompted more high-profile clashes among congressional Democrats, from whether the right to boycott Israel is constitutionally protected to whether the military should have a role in housing migrant children. It’s striking that the Yemen war, an area of broad unity, has now become one of those flashpoints.

Love HuffPost? Become a founding member of HuffPost Plus today.

This article originally appeared on HuffPost.