Congress Might Actually Do Something To Stop Itself From Sucking So Much

It’s hard to find agreement in the politically polarized environment of Washington, but there’s one thing on which members of both parties can agree: Congress sucks.

It sucks to be a congressman. It sucks to be a congressional staffer. And it probably really sucks for their spouses, partners and children. New and old members alike have been speaking out of late.

“The way we’ve done things around here for the past 10 years pretty much sucks,” Sen. John Kennedy (R-La.) said in January 2018 as he called on Senate leadership to let senators vote openly on immigration reform proposals.

“This is a disgrace,” Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.) tweeted after meeting congressional staffers who also worked as bartenders due to low federal pay.

“Congress is increasingly unable to comprehend a world growing more socially, economically and technologically multifaceted — and we did this to ourselves,” Rep. Bill Pascrell (D-N.J.) wrote in The Washington Post on Jan. 11.

Congress has gutted its own capacity to develop legislation and perform oversight, Pascrell explained, an act that has helped shift power away from Congress and toward the executive branch. But now it has an opportunity to reverse its self-imposed lobotomy and empower individual members again ― in the House of Representatives, at least. (Sorry, Sen. Kennedy.)

Earlier this month, the House voted 418-12 to create the Select Committee on the Modernization of Congress to try to fix things. The select committee is charged with producing proposals related to staff pay, retention, benefits and diversity, technology and innovation, and House procedures, including the schedule, the way bills get to the floor and other assorted administrative issues. It will consist of six Democrats and six Republicans appointed by House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) and Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy (R-Calif.) and will require bipartisan support to issue its final report of proposals that the full House could take up. Rep. Derek Kilmer (D-Wash.), the committee’s chairman, is the only member named so far. The committee will have until the end of 2019 to issue a report of recommendations to the full House before it disbands. And if it works, it could change the way Congress does business.

How Congress Got Here

This isn’t the first time Congress has tried to modernize itself. The two major congressional reorganizations in the past century occurred in 1946 and 1970 in response to the revolutionary expansions of the executive branch for President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal and President Lyndon Baines Johnson’s Great Society. Later modernization efforts undercut the authority of committee chairmen, made committee hearings open to the public, expanded subcommittee staff, streamlined committee jurisdiction and implemented new ethics rules.

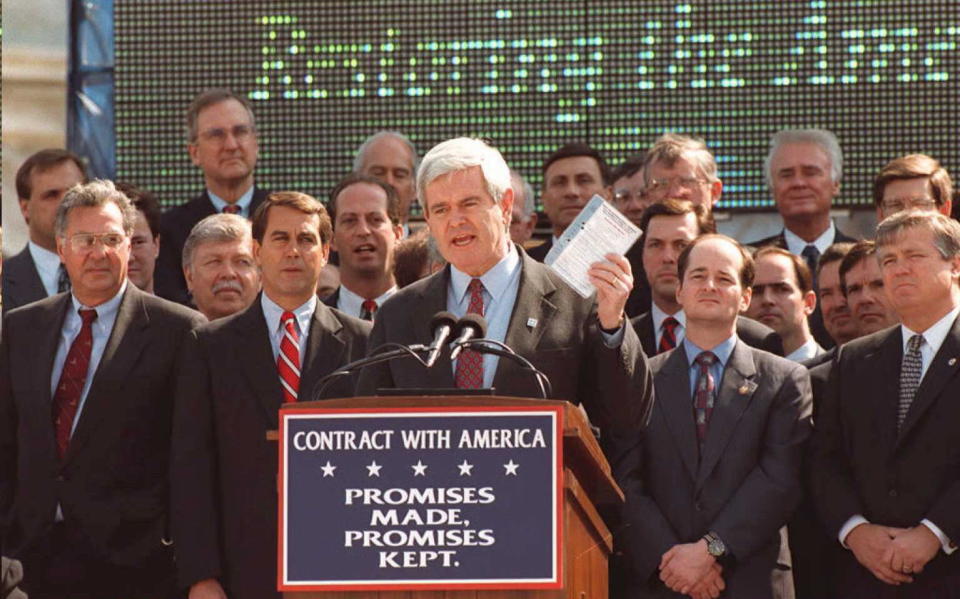

The last time Congress convened a committee to study how to make Congress a better place was in 1993. The committee’s proposals failed after House Democratic Party leadership balked at suggestions that would have undermined their power. Then Democrats lost control of Congress. The new Republican majority, led by Speaker Newt Gingrich (R-Ga.), implemented some of the commission’s modernization reforms but, more important, slashed Congress’ budget, dramatically reduced staff levels, eliminated entire research support agencies and centralized power more than ever in party leadership offices.

In the last 25 years, the Government Accountability Office has shed 2,000 employees. The Congressional Research Service is down 100. The Office of Technology Assessment and its 150 experts were entirely eliminated in 1995 — two years after the invention of the World Wide Web. House congressional committees have shed around 700 staff over the same period of time, while the House overall has seen a slight decline in staff. This underfunding has also left Congress to deal with an antiquated technology system and no team of experts to update and innovate. This capacity decline occurred as the U.S. population rose by 80 million.

Staff pay has stagnated over the same period — and in recent years has even fallen. From 2009 to 2013, the median pay for House counsels dropped 20 percent, and for House legislative directors and assistants, pay fell 13 percent. Senate staff saw similar percentage drops in median pay. This happened just as the cost of living in Washington, D.C., and the surrounding suburbs soared. The median home price in Washington is now above $600,000.

At the same time, power in Congress has been centralized in leadership offices. This has made it almost impossible for lawmakers to work on legislation independently of leadership and get a vote on the floor. This centralization began in the 1980s under Democratic Speaker Tip O’Neill but accelerated under Gingrich and his successor, Speaker Dennis Hastert (R-Ill.), who refused to bring any bills to the floor that did not have majority support within his own Republican Party caucus. This has meant any legislation that might have cross-partisan support but is not supported by leadership has no chance of getting a vote on the floor. This is how former Speaker Paul Ryan (R-Wis.) blocked the Yemen War Powers resolution, a bill to end U.S. support for the Saudi war in Yemen that had backing from Republicans and Democrats.

That some bills with broad bipartisan support can’t even get a vote is “very frustrating,” said Kevin Kosar, vice president for policy at the R Street Institute, a libertarian think tank that supports the select committee. “Members of Congress ― they want to come [to Washington] and they want to work on bills, and then they want to see those bills voted on.”

The Problems

Stagnant pay and reduced staff are ethics and corruption problems. The lobbying, consulting and corporate-funded think tank industries boomed over the past three decades as Congress gutted itself. Corporations actually spend more money on lobbying in Washington than Congress spends total, according to a study by New America fellow Lee Drutman.

“The reason why the lobbyists are powerful is because Congress is weak,” Daniel Schuman, policy director at Demand Progress, a progressive nonprofit, said.

Stagnant pay and fewer options for advancement, combined with student loan debt and the high cost of living in Washington, pull staffers into the private sector.

“You take all your experienced staff and you drive them off the Hill,” Schuman said. “They hit 30 and they don’t want to live in a row house, and, you know, they want to be able to have enough money to pay for day care or they meet a special someone and they can’t afford to stay on the Hill. It takes the people who are experienced and it drives them off.”

Another problem with underpaying staff and letting them flee to K Street or elsewhere is the loss of institutional knowledge and experience. With persistent turnover, Congress is left without strong institutional capacity to do its job of overseeing the executive branch. An executive branch agency may have dozens of staff ready and able to deal with congressional requests while a congressional committee or member office is limited to a handful of staff, many of whom may have limited experience. This dynamic has enabled the executive branch to seize more and more power over the past four decades.

“Power always drifts towards the executive and away from the legislature,” Mark Strand, president of the Congressional Institute, an educational nonprofit affiliated with Republicans in Congress, said. “So, Congress has to fight to keep its power in that system.”

The centralization of decision-making in leadership offices receives criticism from the left, right and center. The left and the right argue that making leadership the sole arbiter of what gets a vote on the floor makes it impossible for their ideas to get heard. Centrists, meanwhile, argue that it suppresses the existing bipartisan agreements that could succeed if only members could vote on them. It also drives a wedge between members and their constituents as a lot of their work will simply be to vote on leadership’s priorities.

“Nobody feels any ownership of it,” Kosar said. “And then [members] have to go back and tell the voters, like, why they voted for it and defend themselves against criticisms.”

This week I went to dive spot in DC for some late night food. I chatted up the staff.

SEVERAL bartenders, managers, & servers *currently worked in Senate + House offices.*

This is a disgrace. Congress of ALL places should raise MRAs so we can pay staff an actual DC living wage.— Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (@AOC) December 3, 2018

How The Committee Came About

The new committee is a victory for a cross-partisan coalition of outside advocacy groups and academics who have pressed Congress to fix itself for the past five years and for the lawmakers who responded by pressing leadership to include it in the House rules package. The committee was approved in a separate floor vote by a 418-12 margin.

The outside coalition includes libertarian and right-leaning voices at the Congressional Institute and R Street Institute, progressive and liberal-leaning nonprofits like Demand Progress and New America Foundation, centrists at the Bipartisan Policy Center and a range of other groups from the good government Issue One to the government technology-focused OpenGov Foundation.

Academics at the Harvard Negotiation Project, in partnership with Issue One, interviewed dozens of members of Congress as part of the outside effort to build support for congressional modernization to see what they thought could be done to increase deliberation and make the legislature work better.

“What was interesting in all these meetings is that when you went in to talk to members ― they just feel that the institution was not performing well, people are just dissatisfied with their job,” Issue One Executive Director Meredith McGehee said.

Each group has its own concerns where disagreement could emerge — particularly on updating the budget process and the enactment of reforms solely in pursuit of the always-elusive bipartisanship. But there is strong agreement among these groups of varying ideology on many of the big issues, such as staff pay and retention, updating congressional technology, increasing Congress’ independent research capacity, devolving some power from congressional leadership to committees and individual members, and changing procedure to make it easier to bring legislation to the floor. That is where these groups believe the committee could make the quickest progress.

Some of the ideas that could come out of the committee that have already been floated, argued or almost enacted in the past include providing new mechanisms for lawmakers to get legislation with broad support to the floor, bringing back the Office of Technology Assessment or some similar body, establishing a Congressional Digital Service to update Congress’ digital infrastructure and increasing funding for support agencies, such as the GAO, CRS and congressional staff.

What these advocates are now watching is who will be appointed to the committee and how much funding it will get.

“This is going to require a lot of research and thinking,” Kosar said. “And so they’re going to need smart, trustworthy people that the committee can rely upon.”

The rules for the committee state that two members must be on the Rules Committee, two must be on the Committee on House Administration and two will be freshmen. How much funding it gets will determine how effective it will be at producing recommendations with broad consensus. And which members are appointed would signal how seriously leadership will take those recommendations when they are presented.

Whether the committee’s eventual recommendations go anywhere will come down to whether the leadership of both parties like what they see and feel enough pressure from their members and the public to make Congress suck just a little less.

Love HuffPost? Become a founding member of HuffPost Plus today.

This article originally appeared on HuffPost.