Carl Levin, Michigan's longest serving US senator, dies at 87

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Carl Levin, a liberal Democrat who rose from a prominent Detroit family to become Michigan’s longest-serving U.S. senator and helped set military priorities and investigate corporate behavior for decades before retiring in 2015, died Thursday. He was 87.

The Levin Center at Wayne State University, which was formed on the senator's behalf after he left the Senate, put out a statement late Thursday, saying, "With great sadness and heavy hearts, the (center and family) announce the passing of Senator Carl Levin."

Levin disclosed in his recently published memoir, "Getting to the Heart of the Matter: My 36 Years in the Senate," that he was diagnosed with lung cancer nearly four years ago, when he was 83.

U.S. Rep. Andy Levin, D-Bloomfield Twp., put out a statement on his uncle's passing:

“Throughout my adult life, wherever I went in Michigan, from Copper Harbor to Monroe, I would run into people who would say, ‘I don’t always agree with Senator Levin, but I support him anyway because he is so genuine, he tells it straight and he follows through.’

Related video: Former Sen. Mike Enzi from Wyoming has died at 77

Gov. Gretchen Whitmer called Levin a champion for Michigan.

"He saw what we were capable of when we came to the table as Michiganders, as Americans, to get things done," she said.

A defender of Senate traditions, even when his own party moved to change them, Levin, who was trained as a lawyer, twice served as chairman of the powerful Armed Services Committee, despite having never served in uniform himself.

As such, he helped set U.S. military strength and policy, including in Afghanistan and Iraq, though he voted against authorizing the use of force in the latter.

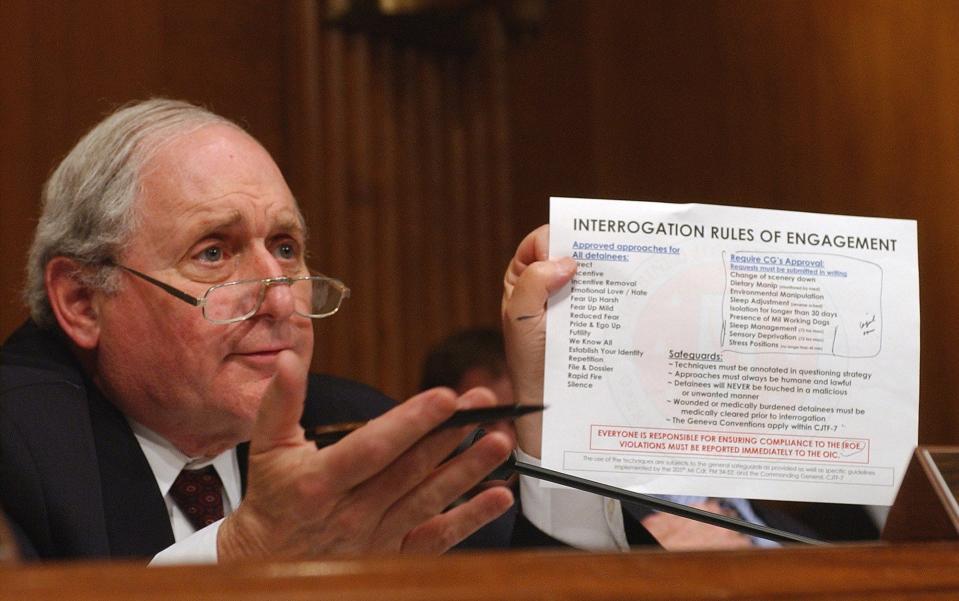

He also investigated questionable Pentagon spending practices and played a key role in overturning the “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” rule that prohibited gay service members from openly acknowledging their sexual orientation prior to 2011. As head of the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, he led probes questioning what he saw as corporate excesses, including those involving Enron, Apple and Goldman Sachs.

As a Michigan senator, he defended the auto industry, supported the bailout of General Motors and Chrysler in 2008-09 and backed numerous projects including Detroit’s RiverWalk, the M-1 Light Rail and the Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary, among others. For years, he fought for a new Soo Lock — efforts that only began to bear fruit after he left office.

“We could not aspire to better service than what he has given our country,” the late U.S. Sen. John McCain, R-Ariz., said of his Armed Services Committee colleague just before Levin’s retirement. McCain, a war hero, went on to call Levin “a model of serious purpose, firm principle and personal decency” and said that while they often disagreed, Levin never went back on his word.

On the same occasion, U.S. Sen. Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., referred to Levin as, “Mr. Integrity.”

The Levin Center said there will be a private funeral and information on a public memorial will be released in the future. Tributes and well-wishes to Levin's family can be sent by email to Levin.Family@wayne.edu.

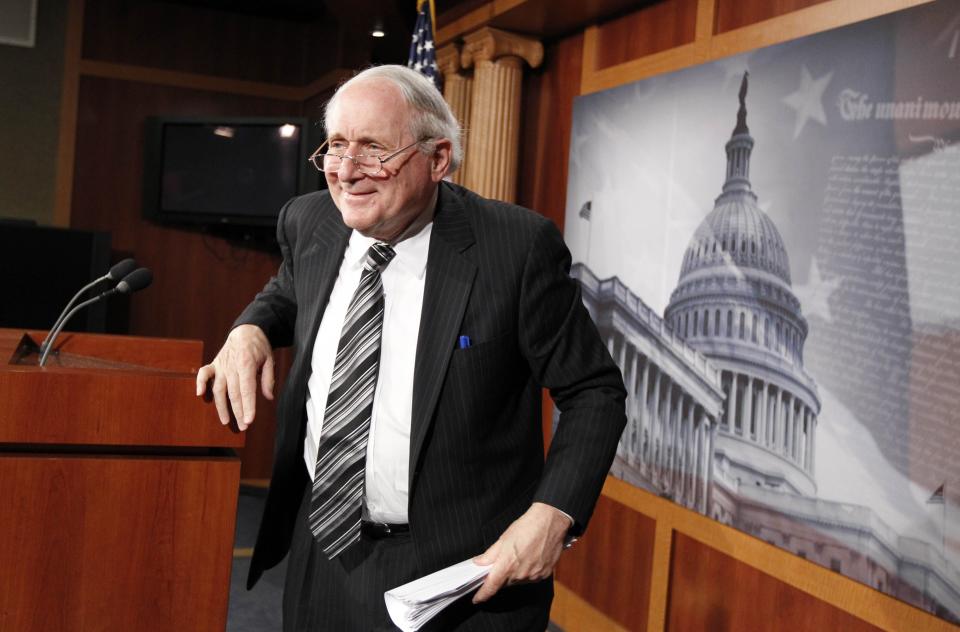

He cut a distinctive figure in the Senate

Often disheveled and wearing a rumpled blue suit, with a signature comb-over and peering over glasses perched at the end of his nose, Levin’s unprepossessing looks masked a sharp wit and fierce intellect that he reserved for the right moment. He was most at ease when deploying his considerable debating skills to trap an argumentative hearing witness or revealing what he saw as hypocrisy.

Once, when questioning Pentagon spending that led to billions being committed to spare parts that would never be used, he remarked, “Looking at the Pentagon supply system is like opening the door to Imelda Marcos’ closet.”

In a 2010 hearing looking into Goldman Sachs, which appeared to take bets against its own clients in the run-up to the 2008 financial crisis, he barked, citing the language of an internal email, “You knew it was a s— deal and you didn’t tell your clients. Does that bother you at all?”

Announcing in early 2013 that he wouldn’t run for a seventh six-year Senate term, Levin, then age 78, said he wanted to spent what little time he had left in office concentrating on policy matters rather than raising the increasingly huge amounts of cash needed to run a Senate race that — had he chosen to run — he likely would have won.

He then settled back in Detroit, taking a senior counsel role at Honigman Miller Schwartz and Cohn LLP and working with a center at the Wayne State University law school named in his honor to educate future leaders and legislators “on their role overseeing public and private institutions.”

Said then-President Barack Obama when Levin announced his retirement, “If you’ve ever worn the uniform, worked a shift on an assembly line or sacrificed to make end’s meet, then you had a voice and a vote in Sen. Carl Levin.”

Plump and balding, he made a career

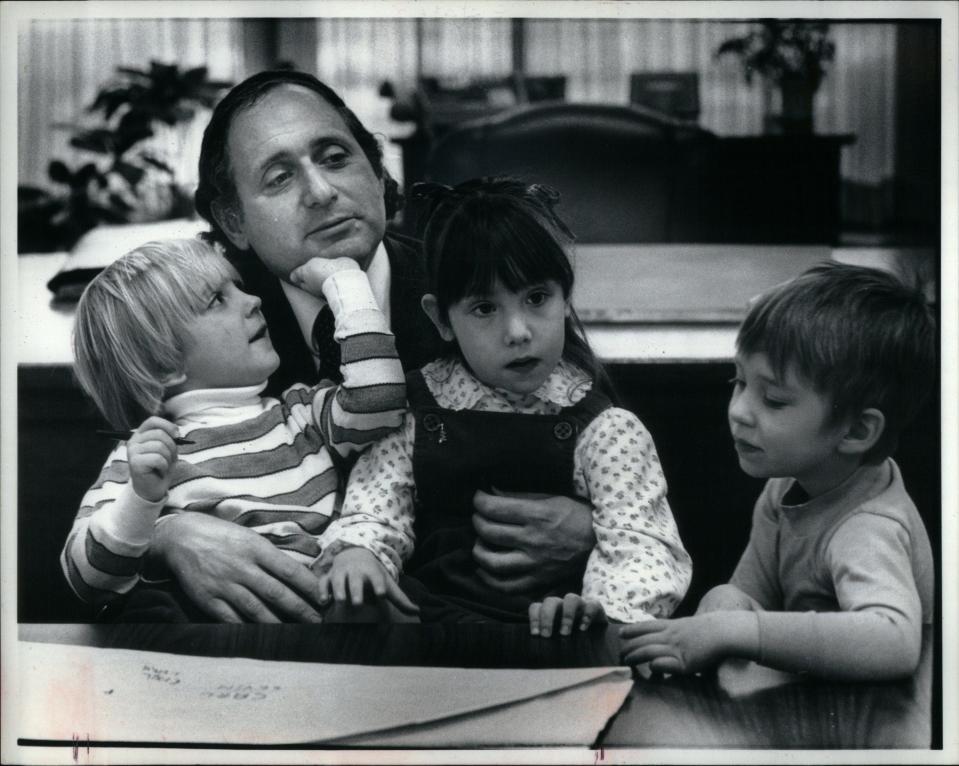

Born in 1934 in Detroit to Saul and Bess Levin, Carl Levin came from — and would continue to represent — a family of lawyers, many of them engaged in social activism and politics. Saul Levin would become a Michigan corrections commissioner. Saul’s brother, Theodore, rose to become the longtime chief judge of U.S. District Court in Detroit — and eventually the namesake of the federal court in downtown Detroit.

Growing up in Detroit, Carl, according to the Almanac of American Politics, worked as a taxi driver and on the assembly line at a Chrysler DeSoto plant before finishing a degree at Swarthmore College and then heading to Harvard for law school, where his beloved brother Sander, three years older than he, had also gone.

Back in Detroit, Carl worked as an attorney, as general counsel for the Michigan Civil Rights Commission and as Detroit’s chief appellate defender. In 1961, he married Barbara Halpern, who would later graduate from Wayne State Law School; they had three daughters together.

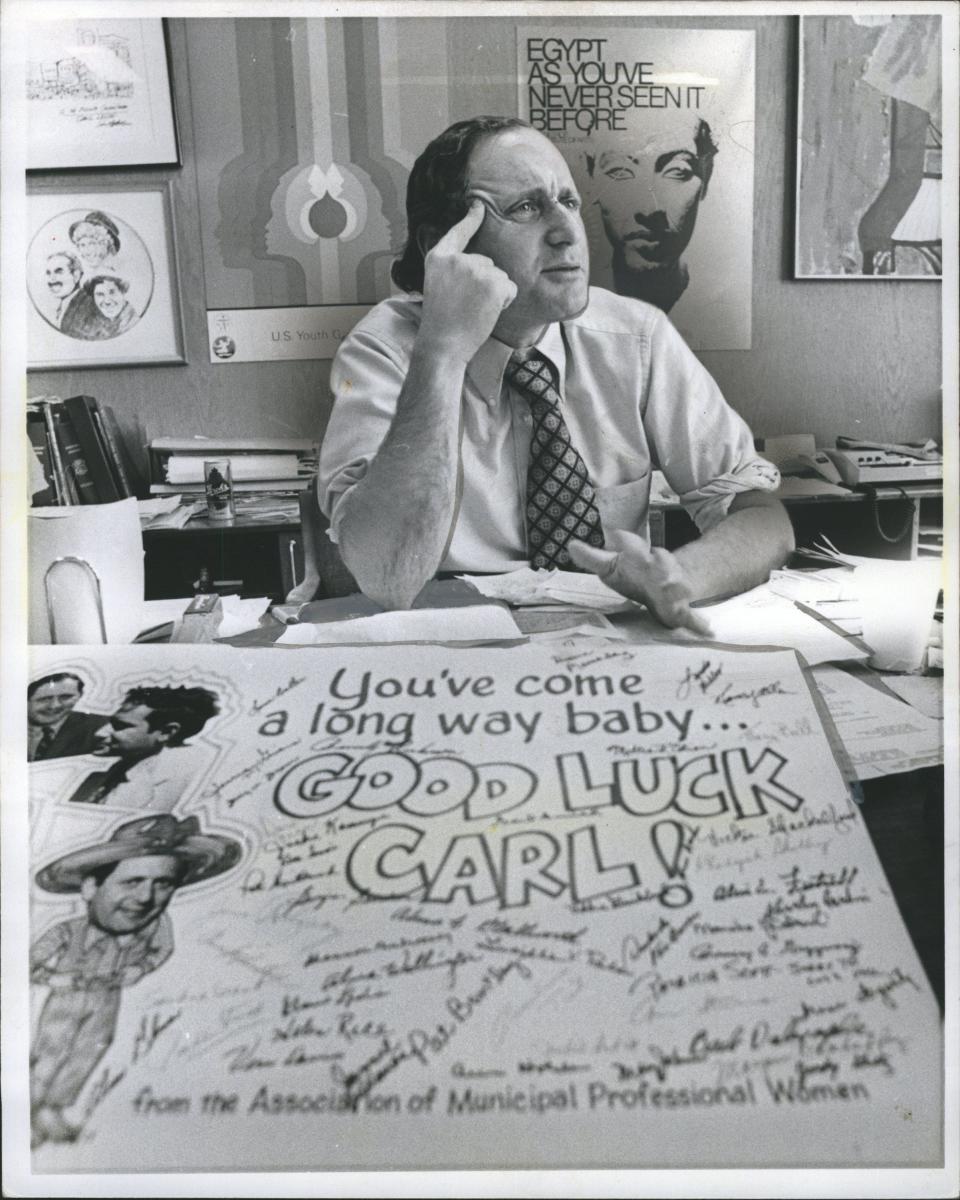

In 1964, Carl’s brother Sandy ran for and won a seat in the Michigan state Senate. Then, in 1968, Carl won a Detroit City Council seat that he held through 1977, serving his last four years on the council as president.

In 1978, when then-U.S. Sen. Robert Griffin, a Republican, indicated he’d had enough with Congress and moved to retire, Carl Levin jumped at the chance. Griffin got back in the race but it was too late. He lost — 52%-48% — to Levin.

Six years later, astronaut Jack Lousma, a tall, handsome Republican, would try to take the seat back, noting in some of his campaign materials his physical attributes — which were different than, as Levin later told the Washington Post, his own “plump, balding and disheveled look.” Levin embraced his attributes instead of running away from them. “It worked,” he later said.

It also didn’t hurt Levin in auto-centric Michigan when it was discovered that Lousma drove a Toyota.

Detroit always remained home for Carl Levin

But whatever the case, Levin would never face a serious threat to the office again. In 1983, his brother Sandy joined the U.S. House of Representatives and for the next 33 years, the Levin brothers would play a large role in helping to set trade policy, auto standards and more.

For a brief time in 2010 and 2011, they each chaired major committees, with Carl over Armed Services in the Senate and Sandy chairing the tax-writing House Ways and Means Committee.

More: Getting to the heart of Carl Levin: Ex-senator reflects on his life, career in new memoir

More: U.S. Rep. Sander Levin will retire from Congress when term ends next year

Throughout, the two brothers remained extremely close, sitting with each other at State of the Union speeches, their families always remaining in touch. Each referred to the other as his closest friend.

Sandy retired in 2019, with his son, Carl’s nephew, Andy Levin, winning the seat and both Carl and Sandy lending support.

Even before Carl’s retirement, however, he was a regular presence in Detroit, living in Lafayette Park, and remaining a lifelong Tigers fan. He helped secure an earmark to try to redevelop Old Tiger Stadium and was associated with numerous causes in and around southeast Michigan.

When Detroit filed for the largest municipal bankruptcy in U.S. history in 2013, Levin was one of the first to rouse the Obama White House, putting together a list of some 200 federal programs through which the city might receive aid while, at the same time, pushing back efforts in the U.S. Senate to try to head off potential help for Detroit.

Around that time, Levin went before a Christian Science Monitor breakfast and told journalists that while his hometown faced challenges, “Detroit is on its way back. I say this as someone who knows almost every block of my city.”

He fought Pentagon overspending, helped make policy

Throughout Levin’s career, he worked to make changes both political and practical. From early on, he railed against Pentagon overspending, introducing legislation to stop the Defense Department from buying “$600 toilet seats and $400 hammers,” as he put it in one campaign ad.

During President George W. Bush’s administration, he and others raised serious questions about a $23.5 billion proposal to lease aircraft from Boeing, trying to determine whether the White House had influenced it.

He also worked to protect Michigan’s military installations, helping to expand operations at the Detroit Arsenal and the Tank Automotive Research, Development and Engineering Center (TARDEC) in Macomb County and protect aircraft at Selfridge Air National Guard Base in Harrison Township.

While Levin often called for reining in Pentagon spending and had military brass come before him to justify their requests, he seemed to revel in the behind-closed-doors negotiating that led to each year’s defense authorizations — long, detailed pieces of legislation that represented months of give-and-take and set policy and helped guide spending.

The USS Carl M. Levin, a guided missile destroyer launched earlier this year for trials but not yet formally commissioned for duty, was named for him.

But he wasn't always successful

Levin had his setbacks, however.

For years, he pushed unsuccessfully to close the prison at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, for instance. And as a longtime Democratic National Committee member, he argued against Iowa and New Hampshire having the beginning of the primary season in each presidential campaign to themselves, arguing that a bigger state like Michigan would be more representative.

He also failed to stop the Senate from passing higher emission standards for automakers in 2007.

In 2013, he argued against his own party, saying that if Senate rules regarding the use of filibusters — which required a supermajority vote on some issues — were going to be changed for judicial nominees other than those to the Supreme Court, the rule change itself should require a supermajority and not a simple majority.

Failing to do so, he argued, would undermine long-standing practices that protected minority interests in the chamber.

“If a Senate majority demonstrates it can make such a change once, there are no rules which binds a majority and all future majorities will feel free to exercise the same power,” said Levin.

Democrats made the change anyway, however. Then, in 2017, a Republican-led Senate did exactly as Levin predicted — changing the rule again to allow Supreme Court nominees to be confirmed on a simple vote and confirming Neil Gorsuch and, later, Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett.

Levin remained supportive of the filibuster, however. This year, he and Richard Arenberg, interim director of the Taubman Center for American Politics and Policy, wrote a piece for the Wall Street Journal calling efforts to abolish it "shortsighted" and calling for reforms instead, including those that would force senators to remain on the floor throughout the debate. "If (progressives') agenda is worth fighting for — and it is — it’s worth the inconvenience involved in confronting the threat of the filibuster and forcing the obstructors to stand up and talk for days on the Senate floor," they wrote.

Levin also wasn’t always beyond criticism himself, either. In 2013, he beat back an attempt by some in his own party, namely Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand, D-N.Y., to take military command out of decisions about when or when not to prosecute sexual assault allegations, with Levin arguing it was important for military culture that commanders remain in charge. While a vote hasn't happened yet, this year, Gillibrand has secured the backing of enough senators to win a vote on the bill, which could allow independent prosecutors to handle any felonies charged against military personnel that carry a punishment of more than a year in prison.

He also was criticized by some conservative media outlets for pressing the Internal Revenue Service to look into the tax status of some nonprofit groups, asking whether they were engaging in partisan activity disallowed under federal rules. But Levin said he did not intend for his questions to apply only to conservative groups but to any of those coming under the law.

Once, in 2010, he was hit in the face with a pie after a rant by an anti-war protester in Michigan. He shrugged it off saying, “They didn’t hurt me, but they hurt their cause even more than their own extreme words had already done.”

He was a sought-after voice on policy matters and a fierce investigator

For all of that, Levin was considered a go-to legislator, especially when it came to matters of defense policy, helping to shape — or sharply criticize — America’s handling of its foreign wars.

He had a hand in raising pay for military personnel and when he voted against the use of force in Iraq, it was only to give inspectors more time to determine whether Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction.

He supported military intervention in Afghanistan but was a staunch believer that Afghan security forces should be given control of the country as quickly as was possible.

In 2006, TIME Magazine called him one of the nation’s 10 best U.S. senators.

“This is a senator’s senator,” said former U.S. Sen. Claire McCaskill, D-Mo., who served with him on the Armed Services Committee. “There are no sharp elbows. There is no heated rhetoric. … Carl is methodically doing the grind-it-out work of legislating. He has the tools of a great senator: intellect, integrity, good manners and an unsurpassed work ethic.”

As chairman of the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, Levin reserved some of his toughest questioning for corporate executives and others he thought were taking unnecessary risks with people’s futures or otherwise fleecing customers or taxpayers.

In 2002, when Levin hauled members of Enron’s board before the panel, he and others sharply criticized them for failing to act despite what appeared to be ample red flags that the energy company was being mismanaged and in dire straits.

Speaking about a former director’s script for an interview with Enron’s chief financial officer around that time, Levin said, “You can’t get much more deferential and obsequious. Why don’t you call up and say, ‘What in God’s name is going on?’ ”

In 2013, Levin brought Apple executives before the subcommittee to raise attention to it parking some of its top assets — and their profits — in Irish subsidiaries that paid little in taxes. Levin never told CEO Tim Cook that his company broke the law but suggested such practices shortchanged U.S. taxpayers.

When Sen. Rand Paul, R-Ky., argued that Levin should apologize for calling a hearing to “bully” an iconic American company, Levin charged back, saying, “They don’t have a right to decide in my book how much taxes they’re going to pay and where they are going to pay them."

"You can apologize to anyone you want," Levin told Paul. "This subcommittee is not going to apologize to Apple.”

Contact Todd Spangler: tspangler@freepress.com. Follow him on Twitter @tsspangler. Read more on Michigan politics and sign up for our elections newsletter. Staff writers Paul Egan and Clara Hendrickson contributed to this story.

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: Carl Levin, Michigan's longest serving U.S. senator, dies at 87