Here's How You Can Help Stop A Sexual Assault Before It Happens

Earlier this year, a woman named Jackie Fuchs reached out to The Huffington Post saying that she was ready to come forward with a secret she had lived with most of her life: When she was 16 and the bassist for the Runaways -- going then by the name Jackie Fox -- she was raped by the rock band's creator in front of several bandmates (including Joan Jett) and a handful of hangers-on.

She was coming forward, Fuchs said, to help change the culture and conversation around sexual assault, to let women and girls know that, even in the face of the Rolling Stone story debacle, it was OK to speak out. Just as importantly, she had come to think of those who saw her being raped not as accidental accomplices in a horrific crime, but as victims themselves.

HuffPost spoke with a number of those bystanders, and they confirmed Fuchs' suspicion that they, too, were haunted by the experience. (You can read their stories in this week's HuffPost Highline feature, "The Lost Girls.") A growing body of research also shows that Fuchs' insight has real merit: Witnesses to sexual assault often carry that burden with them, and rethinking the role of bystanders could help prevent future assaults.

The current approach to rape prevention -- telling men and boys that no means no and warning women not to get too drunk -- has been failing for years, as the former feel as if they're being treated like rapists and the latter feel unfairly blamed. “Most people are not pro-rape -- that’s not our problem,” said Dr. Dorothy Edwards. “Most people are fundamentally good and want this to stop.”

Love HuffPost? Become a founding member of HuffPost Plus today.

After becoming director of the University of Kentucky’s Violence Intervention and Prevention Center in 2005, Edwards began looking at public health and the role of the bystander as a way to reframe how we talk about rape prevention. The majority of her students were not rapists or victims, but they found themselves in situations where intervening could prevent an act of sexual violence or gender bullying. Her students didn’t need to feel guilty, Edwards realized. They needed tools on how to be better bystanders.

When she started her work, Edwards said she wasn't prepared to hear the stories of people who had witnessed sexual violence and failed to act. Now, she said, “Hardly a training doesn’t go by when six or seven people come up to me at the end and say, ‘That was me. I have carried this my whole life, I know what I did and I could have stopped it.’”

Edwards found that people aren't sure how to respond when witnessing a potential sexual assault, especially when other people are standing around as well. Add in prevalent myths about rape, the presence of drugs and alcohol, and the need to read complicated social cues, and it can be hard to know how or when to intervene. Bystanders sometimes don’t even know what they’re looking at.

Last year, Sarah Nicksa, an assistant professor of criminal justice at Widener University, published a study comparing bystanders’ responses to three scenarios -- a physical assault, a theft and a sexual assault. Participants were least likely to intervene in the sexual assault.

"Sexual assaults in college settings often occur in alcohol-infused situations, such as parties or get-togethers," said Nicksa in an email. "Sexual assaults and rapes are often not considered 'real rapes' by victims, friends, family, or the criminal justice system unless they involved force, violence, and were committed by a stranger with a weapon. So when a bystander is aware of a sexual assault, they may not see it as a problem or an emergency, due to the social norms of their group and setting. They may look around for cues to see if others define it as an emergency, and seeing none, do nothing."

Dr. Victoria Banyard, a psychology professor at the University of New Hampshire who studies the effectiveness of rape prevention programs, said that educating future bystanders is critical. “People are watching what’s going on and they are not labeling it a problem,” she said. “Or they are starting to feel it’s a problem but they are not sure they are the ones to do anything about it. Or they get to a point where they are worried about their own safety.”

Edwards founded the nonprofit Green Dot, etc., based on the idea that teaching young people to better anticipate at-risk situations is key. Her aim is to figure out direct and indirect methods of intervention and to develop a peer culture in which rape prevention is normalized.

On a basic level, when a student makes a sexist remark, for example, a peer can call that person out. Or in the scenario that comes up most often during trainings, students can help a female friend who has gotten drunk and is in danger of being taken advantage of. In those situations, they are taught how to intervene in ways that can be non-confrontational, employing tactics such as creating a distraction -- telling the would-be assailant, for instance, that his car is being towed. Or persuading the woman to come with them instead of going with him. Or staying close to her until the guy gives up and moves on. The key is getting students to rely on their own resourcefulness to become smarter bystanders.

We recently mentioned the new focus on bystanders to a Washington, D.C., political operative, and she recalled an experience that suggests the approach's potential. She was out with friends and noticed a young woman nearly passed out on the bar, while someone else circled furtively around. He eventually helped the woman out of the bar. Our bystander, who'd been watching the scene unfold and growing increasingly concerned, followed them out. On the sidewalk, she told the man that if he tried to leave with the woman, she'd call the police. The guy walked off, leaving the woman on the sidewalk, oblivious to the assault she might have just avoided.

In her first year running a bystander program, Edwards trained a little more than 10 people. By the time she left the University of Kentucky to run Green Dot full time, she was training 3,500 student volunteers enrolled in her six-hour sessions. Roughly 45 percent of those students were men. Edwards said there are now Green Dot programs across the country and in every military branch.

Programs such as Green Dot, Bringing In the Bystander, and Coaching Boys Into Men have begun to show results. A recent five-year study funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found 50 percent reductions in sexual violence in Kentucky high schools that implemented Green Dot.

“The findings of that study were strong,” said Dr. Sarah DeGue, a behavioral scientist in the CDC’s violence prevention division. But she added that more studies need to be done. “We don’t know whether the effects we are seeing there were caused by Green Dot,” she said.

Last year, the White House joined in with the launch of a bystander awareness campaign, “It’s On Us.”

Researchers tend to compare the bystander message to successful public health policies like condom distribution for HIV prevention. Dr. Elizabeth Miller, chief of the division of adolescent and young adult medicine at the Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, compares it to designated driver campaigns.

“It’s not saying, 'You are the problem,'” explained Miller, who has published research on bystander education. “It taps into a sense of generosity and sense of connectedness.”

'Full Battle Rattle'

![Rebekah Havrilla, out on patrol in Afghanistan. The former Army sergeant and Explosive Ordnance Disposal specialist enlisted in 2004, seeking out job training, education, "some patriotic element" after 9/11 and a way out of South Carolina. "I went in with the idea of making a career out of it," she says. "I thought, I can't be Special Forces, I can't do Rangers because I don't have a penis -- closest thing I can get to actually doing that type of job is EOD [Explosive Ordnance Disposal]."](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/QAMrkdjN8kI0f9UC2AD1fQ--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MA--/https://img.huffingtonpost.com/asset/55a09ac014000001079a7b4b.jpg)

Shot Hole

Rebekah Havrilla

Tia Christopher

Women Veterans

Jungle

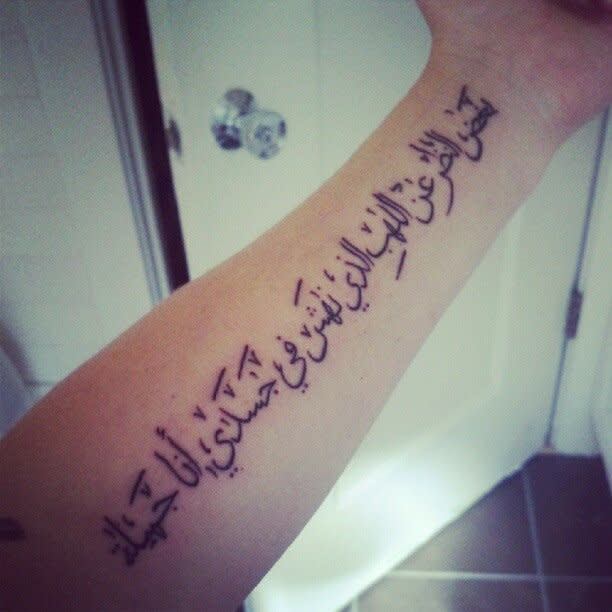

'I'm Beautiful Despite The Flames'

Tia Christopher

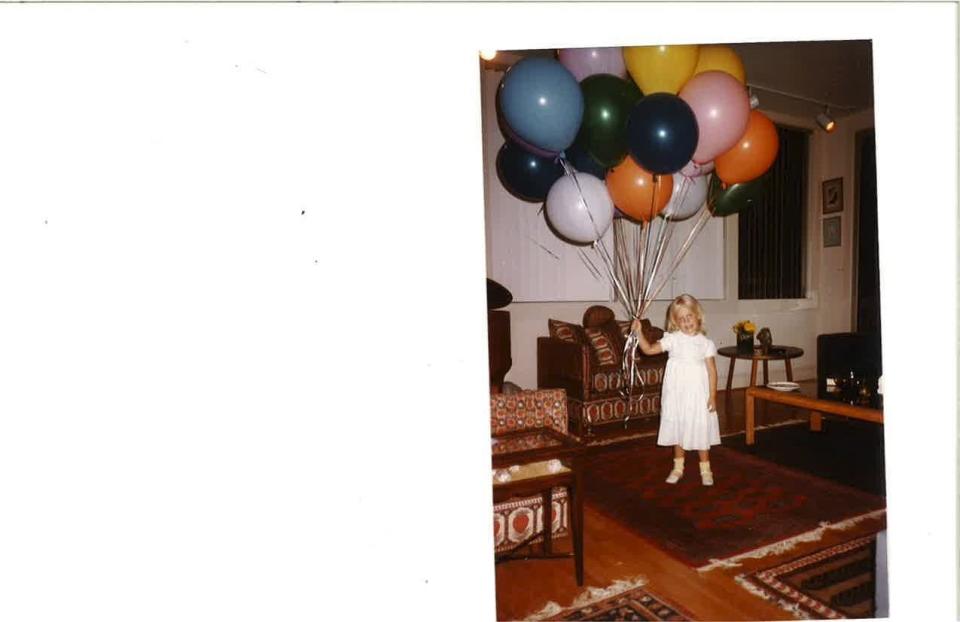

Balloons

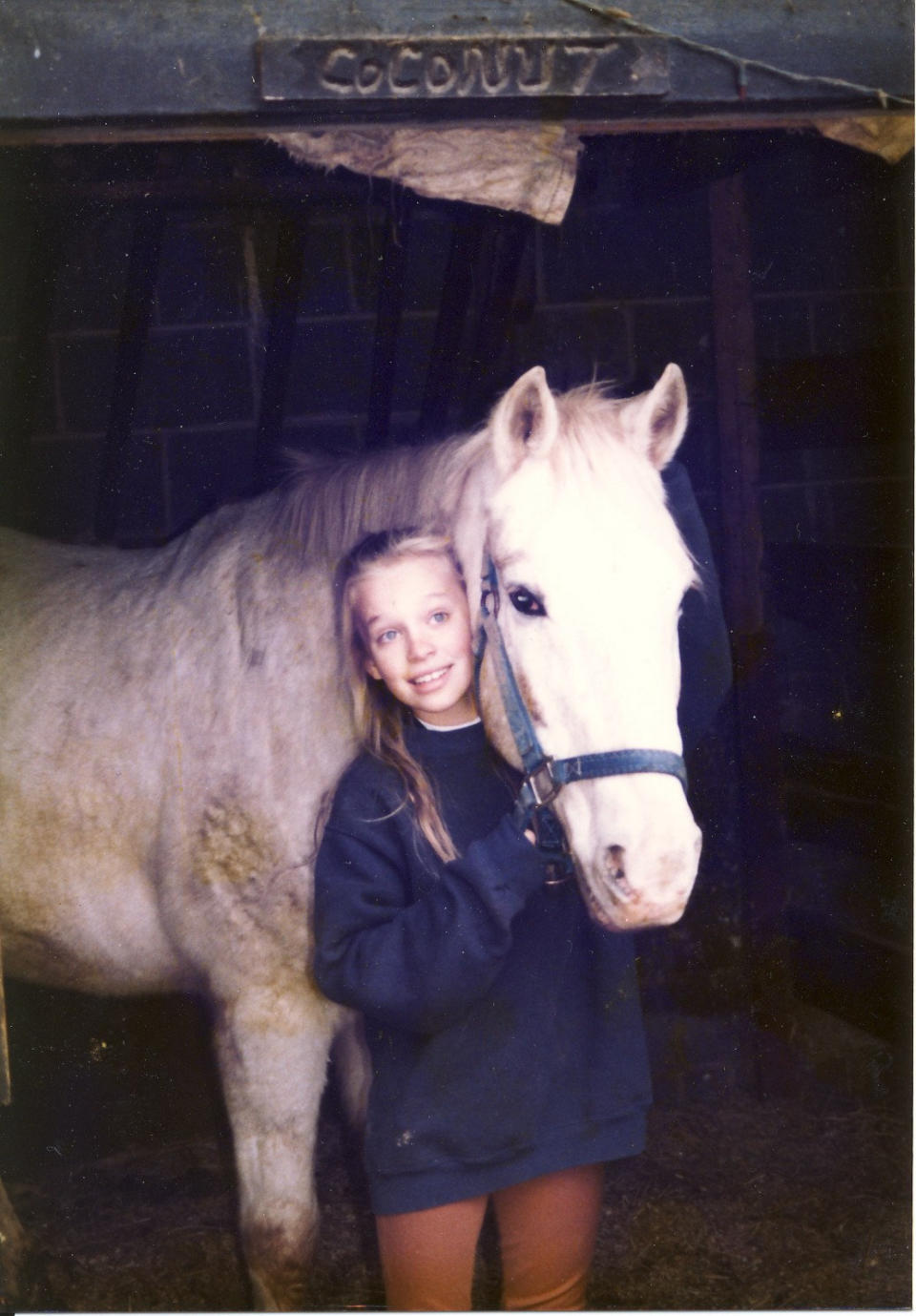

Claire & Coconut

Claire Russo Salutes Her Cousin

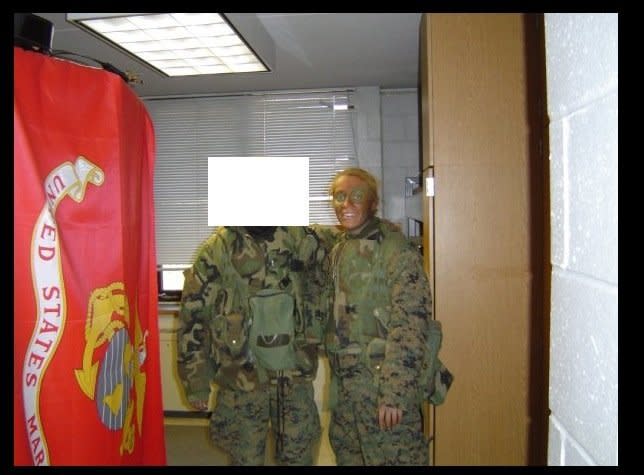

Basic School

Fallujah Courtyard

'Citizen Of Courage'

Russo And San Diego DAs

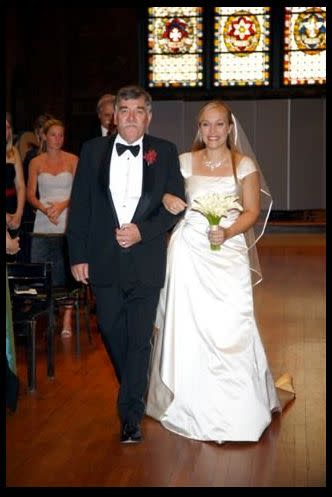

Down The Aisle

Claire And Josh Russo

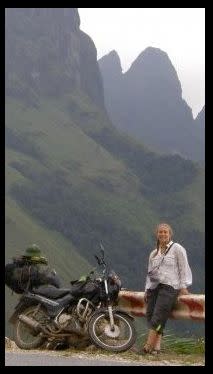

Russo And Her Motorcycle

'Marawara'

Claire, Josh And Genevieve Russo In Paris

St. Genevieve

Marti Ribeiro In Front Of Village

Interviewing

'Afghan Girls On Rooftop'

Ribeiro In 2006

'Soaked To The Bone And Miserable'

Marti Ribeiro And Her Daughter Bela

This article originally appeared on HuffPost.