PHOTOS: Brazil's Kayapo Meet Modernity On Their Own Terms

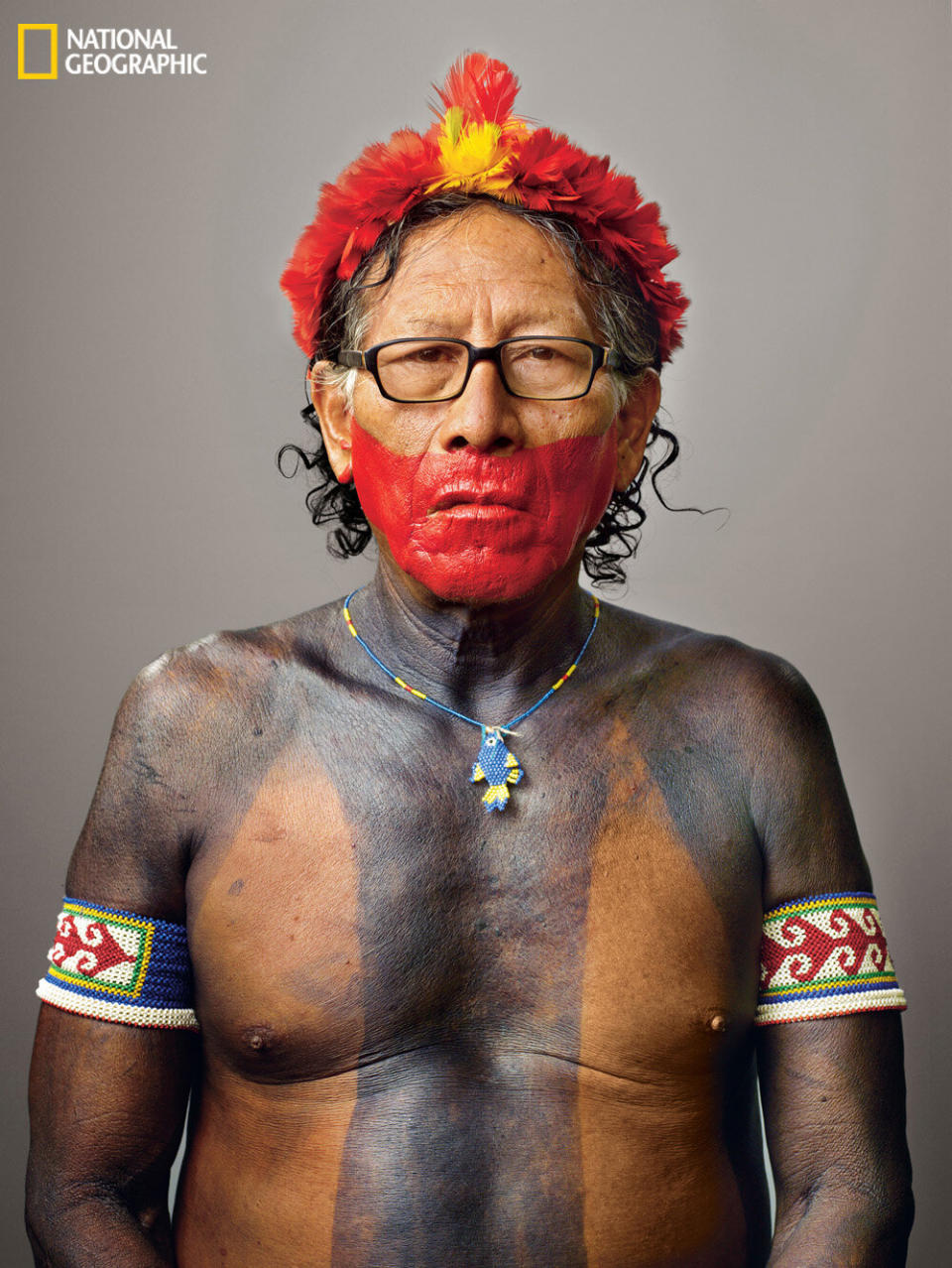

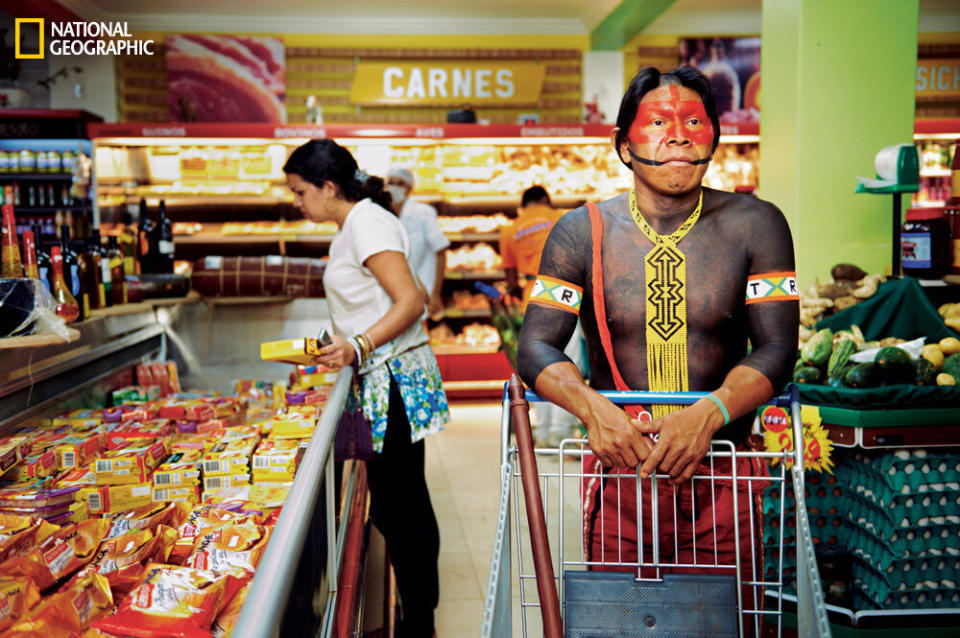

The Kayapo of Brazil challenge every stereotypical image of the indigenous people of the Americas.

A powerful and rapidly growing group among Brazil's 240 indigenous tribes, the Kayapo consists of roughly 9,000 people, While some cannot read or write, others have started Facebook pages and shop in supermarkets.

According to National Geographic reporter Chip Brown, the group's particular success and relative wealth seems to stem precisely from its fierce assertion of tradition paired with an openness to new technologies and modes of communication. That said, the road has been difficult and paved with opposition along the say.

In the January issue of National Geographic, Brown writes:

Love HuffPost? Become a founding member of HuffPost Plus today.

At first glance, Kendjam seems a kind of Eden. And perhaps it is. But that’s hardly to say the history of the Kayapo people is a pastoral idyll exempt from the persecution and disease that have ravaged nearly every indigenous tribe in North and South America. In 1900, 11 years after the founding of the Brazilian Republic, the Kayapo population was about 4,000. As miners, loggers, rubber tappers, and ranchers poured into the Brazilian frontier, missionary organizations and government agencies launched efforts to “pacify” aboriginal tribes, wooing them with trade goods such as cloth, metal pots, machetes, and axes. Contact often had the unintended effect of introducing measles and other diseases to people who had no natural immunity. By the late 1970s, following the construction of the Trans-Amazon Highway, the population had dwindled to about 1,300.

But if they were battered, they were never broken. In the 1980s and ’90s the Kayapo rallied, led by a legendary generation of chiefs who harnessed their warrior culture to achieve their political goals. Leaders like Ropni and Mekaron-Ti organized protests with military precision, began to apply pressure, and, as I learned from Zimmerman, who has been working with the Kayapo for more than 20 years, would even kill people caught trespassing on their land. Kayapo war parties evicted illegal ranchers and gold miners, sometimes offering them the choice of leaving Indian land in two hours or being killed on the spot. Warriors took control of strategic river crossings and patrolled borders; they seized hostages; they sent captured trespassers back to town without their clothes.

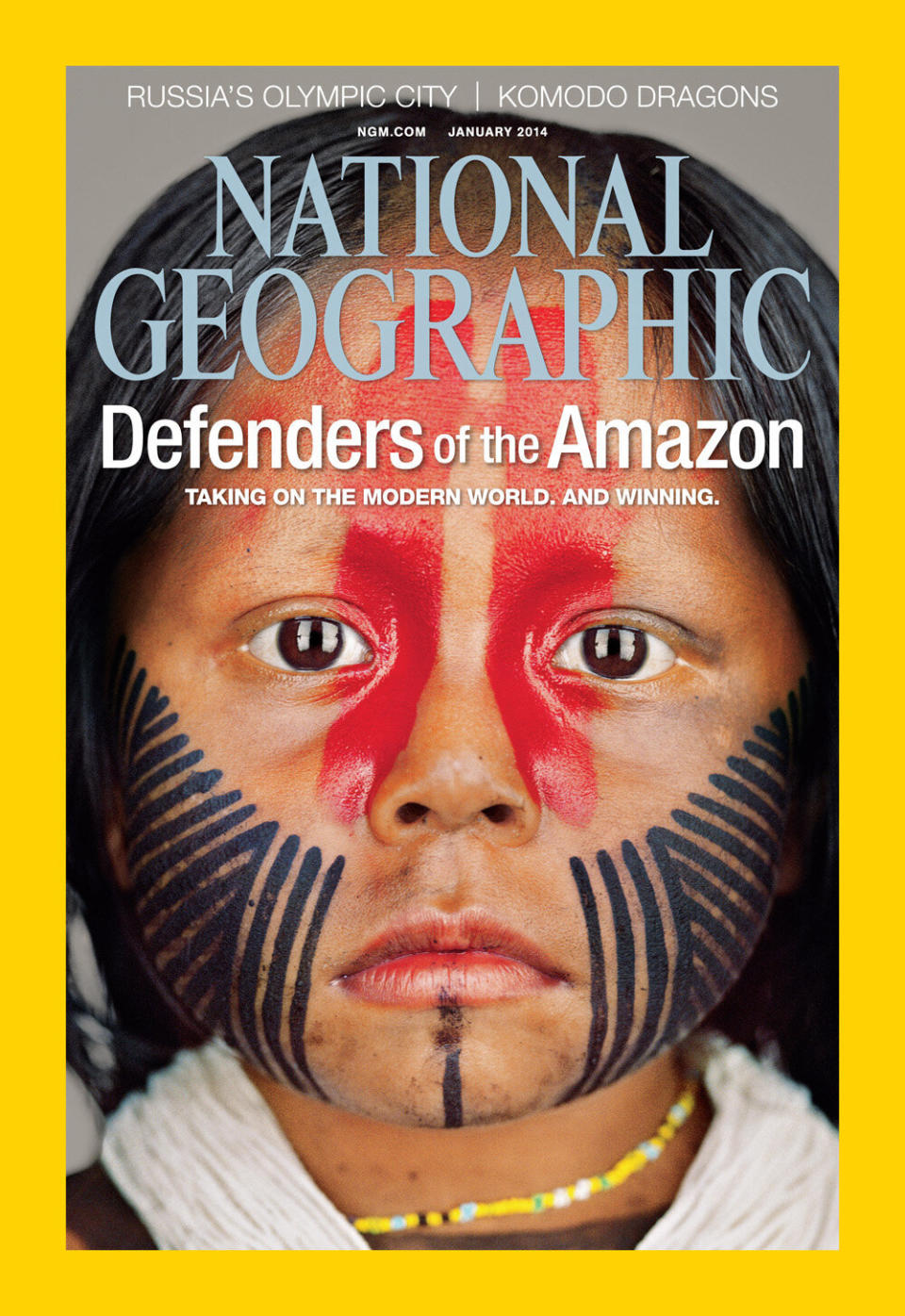

Read more about the Kayapo and view Martin Schoeller's accompanying photography on the National Geographic website or in the January issue of National Geographic.

This article originally appeared on HuffPost.