Utility Giant Sets Up Critical Test For Top 2020 Democrats On Nuclear

One of the nation’s largest utilities last month announced plans to request new licenses for 11 nuclear reactors, setting up a critical new test for Democratic presidential candidates on how to achieve zero-carbon energy generation.

Duke Energy, headquartered in Charlotte, North Carolina, said it plans to submit its renewal applications for reactors at six power plants in the Carolinas starting in 2021, which could put those decisions in the hands of a new White House if a Democrat unseats President Donald Trump next year.

As it stands, it’s unclear where the top contenders for the Democratic presidential nomination would stand on relicensing. Despite intense focus on energy and climate policy, on which there are clear divisions among the candidates, the issue of nuclear power has largely been ignored in the Democratic debates. Sen. Cory Booker (D-N.J.) and businessman Andrew Yang are all in, pledging to keep open safe plants and invest heavily in researching advanced reactors. On the opposite end of the spectrum is Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.), who promised to halt construction on new reactors and issue a moratorium on nuclear plant license renewals.

The views of the candidates in between are less certain. Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) endorsed erstwhile climate candidate Jay Inslee’s proposal, which calls for keeping existing nuclear plants open. But at a CNN town hall last month, she vowed to start “weaning ourselves off nuclear energy” with the goal of shutting down existing plants by 2035.

Former Vice President Joe Biden, long a critic of the nuclear industry, proposed new funding for advanced reactors but hasn’t taken a definitive position on extending the lives of existing nuclear plants.

Warren and Biden, now the top two in several polls, gave “unclear” responses to The Washington Post’s survey on nuclear energy. The Biden, Warren and Sanders campaigns did not respond to requests for comments on the record.

The case for nuclear power as a source of low-carbon energy is fairly straightforward. Reactors currently produce 20% of the country’s electricity, while hydroelectric, wind and solar power combined generate 17%. The only country that has significantly slashed emissions while remaining an industrial powerhouse is France, which converted over 70% of its power generation to nuclear after 1979.

Halving global emissions in the next decade ― which scientific projections say governments must do to avoid catastrophic warming ― would require unprecedented changes to the world’s energy systems.

It’s a lot harder to make those changes without at least maintaining existing nuclear reactors. The United States would need to increase renewable power generation from 0.6% to 2% per year to achieve net-zero emissions from the utility sector by 2050, according to calculations from assistant professor Leah Stokes of the University of California, Santa Barbara. To totally eliminate emissions from vehicles, the nation’s top source of planet-heating gas, the U.S. would need to double its electrical output and increase construction of renewable energy projects sevenfold ― a mammoth undertaking, particularly when the worldwide buildout of renewable energy projects is in decline for the first time since 2001.

But hitting that target by 2030 without adding new nuclear plants, as Warren has proposed, would require the deployment rate of renewable energy projects to increase 17 times faster than the current average. Under Sanders’ plan, which aims to decarbonize the energy sector while decommissioning nuclear reactors, it would need to be 25 times faster.

The case against new nuclear plants is also fairly straightforward. Nuclear waste remains toxic for 250,000 years, roughly the same amount of time since early humans first evolved. There’s no good way to store spent fuel rods, despite recent progress in storing waste in remote underground caverns in Northern Europe and developing powerful lasers to alter atomic nuclei. That makes existing plants radioactive, literally and politically, particularly in a heated primary. Nevada, where the federal government has long stored waste in desert facilities and has proposed a controversial waste storage facility in Yucca Mountain, is an early-voting primary state, and nuclear storage is a top concern there.

Nuclear plants are extremely expensive, both to build and operate. The only new nuclear plant under construction, in Georgia, is running about four years behind schedule, and its cost surged to $28 billion last year, double the initial estimate of $14.1 billion. And it could climb higher. South Carolina spent $9 billion on two new reactors only to abandon the project over costs and delays after hiking electricity rates in the state to cover nearly $4 billion of the cost overruns.

Despite campaigning heavily in the early-voting Palmetto State, presidential hopefuls have yet to even remark there on that textbook pocketbook issue, said Tom Clements, an environmental activist in South Carolina.

“They have the gall to come here and they just ignore it,” he said of the costs.

The high cost of building nuclear plants makes it impossible to compete with cheap fracked gas as coal plants are shuttered at a steady pace.

Putting a price on carbon dioxide emissions ― or, at the very least, eliminating fossil fuel subsidies ― would make it easier for the industry to compete against gas. But nuclear’s carbon-free rivals are catching up. Wind and solar generators outcompeted nuclear plants in mid-2019 on both cost and construction speed, the annual World Nuclear Industry Status Report found.

“Stabilizing the climate is urgent, nuclear power is slow,” Mycle Schneider, lead author of the report, told Reuters. “It meets no technical or operational need that low-carbon competitors cannot meet better, cheaper and faster.”

That’s partly why no new reactors have been licensed in a quarter of a century. It’s also why 59 of the country’s currently licensed 97 reactors face retirement by 2040, including 11 whose credentials expire by 2025.

But extending licenses on existing reactors is another story.

“It’s like renewing your driver’s license. We don’t view it as a litmus test,” said Neal Cohen, a vice president at the industry-backed Nuclear Energy Institute. “License renewal is not a controversial idea.”

At a moment when HBO’s hit series “Chernobyl” and the 2011 nuclear disaster in Fukushima, Japan, offer stark reminders of how destructive radiation can be, Clements took a markedly different view of extending licenses on reactors already relicensed once before.

“These reactors get older, the components age and there are safety risks associated with that,” he said.

But Duke Energy instead pointed to the threat of inflaming the climate crisis with increased emissions. The utility’s existing nuclear fleet “avoided the release of about 54 million tons of carbon dioxide ― equivalent to keeping more than 10 million passenger cars off the road,” the company said. The move, moreover, was part of a broader announcement last month that Duke planned to halve its emissions by 2030 and zero them out by 2050.

That, Duke spokesperson Rita Sipe said, is why the company is announcing the renewals now. The first reactors for which Duke plans to apply for renewals are at its Oconee plant in Greenville, South Carolina. Nuclear Regulatory Commission filings show the credentials for the three reactors there don’t expire until 2033. But the company “projects years into the future.” And the U.S. nuclear industry’s precarious outlook makes predictions difficult.

Yet shoring up political support from a potential next president could be essential. And while a Duke spokeswoman declined to “speak directly to the politics,” South Carolina Democrats go to the polls at the end of February to decide whom that might be.

Clarification: Duke Energy plans to start submitting renewal applications for nuclear reactors in 2021, not to submit them all that year.

Related Coverage

Trump Administration’s Climate Report Raises New Questions About Nuclear Energy’s Future

Bernie Sanders Unveils $16 Trillion Green New Deal To Combat Climate Crisis

Cory Booker Compares Anti-Nuclear Democrats To Republican Climate Deniers

Also on HuffPost

Love HuffPost? Become a founding member of HuffPost Plus today.

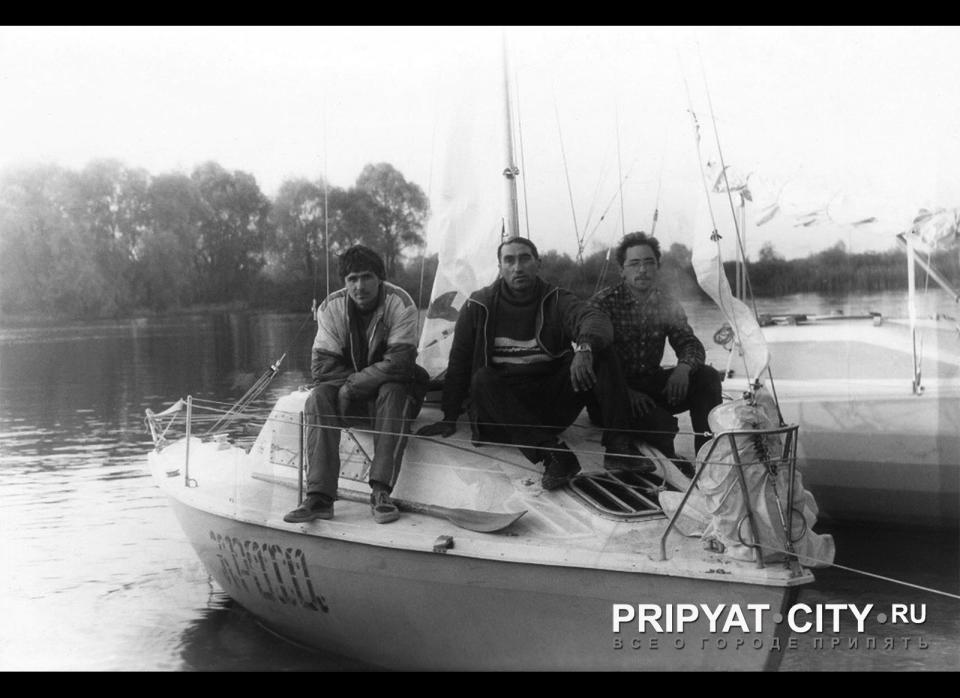

Pripyat before the disaster.

Pripyat before the disaster.

Pripyat before the disaster.

Pripyat before the disaster.

Pripyat before the disaster.

Pripyat before the disaster.

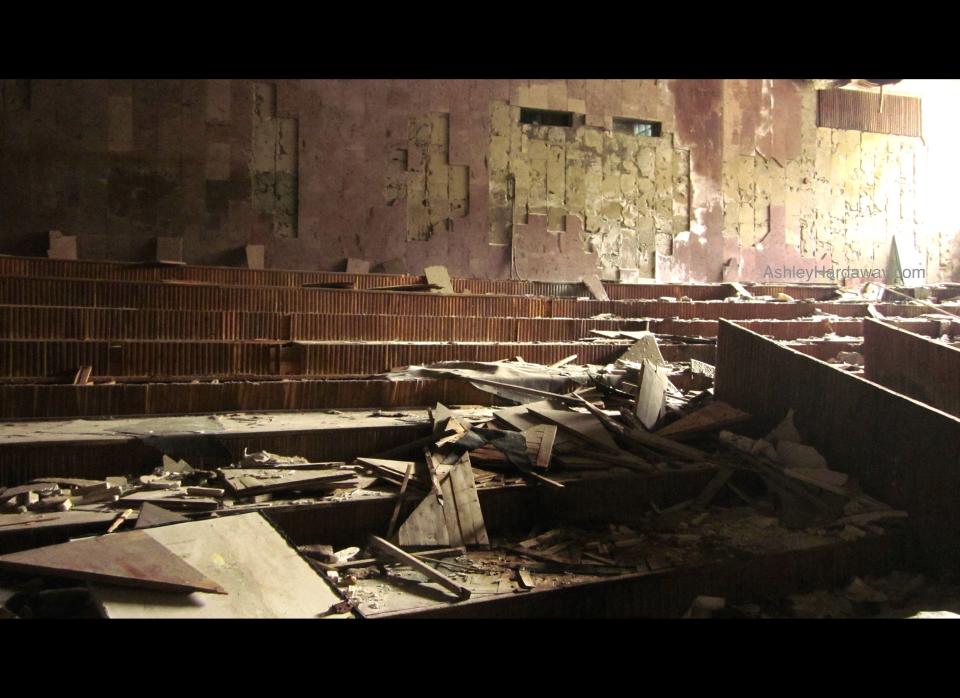

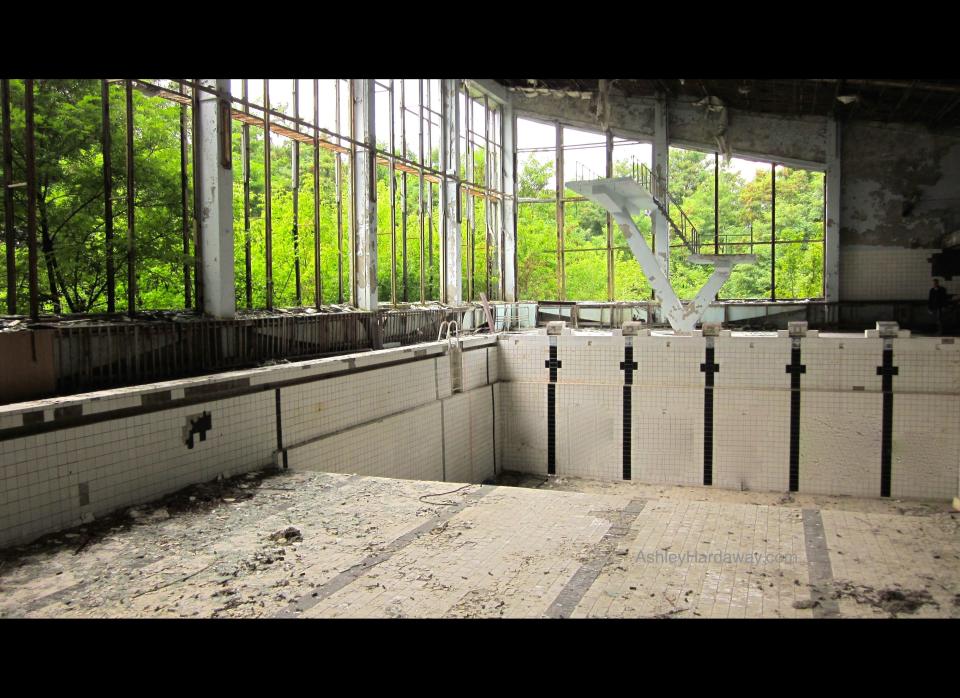

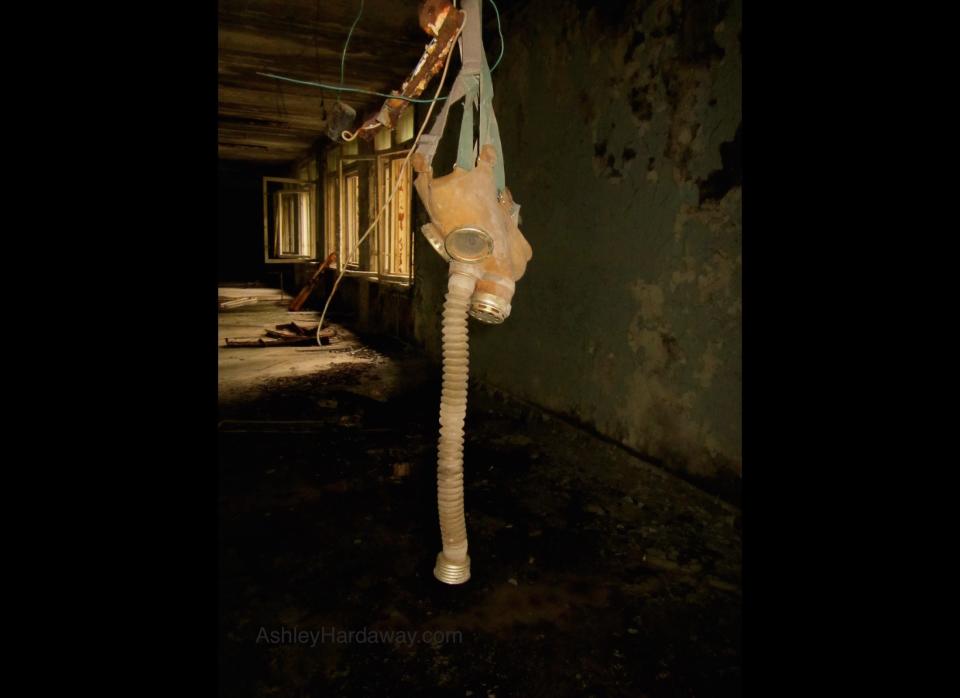

Chernobyl after the disaster.

Chernobyl after the disaster.

Chernobyl after the disaster.

Chernobyl after the disaster.

Chernobyl after the disaster.

Chernobyl after the disaster.

Chernobyl after the disaster.

Chernobyl after the disaster.

Chernobyl after the disaster.

Chernobyl after the disaster.

Chernobyl after the disaster.

Chernobyl after the disaster.

This article originally appeared on HuffPost.