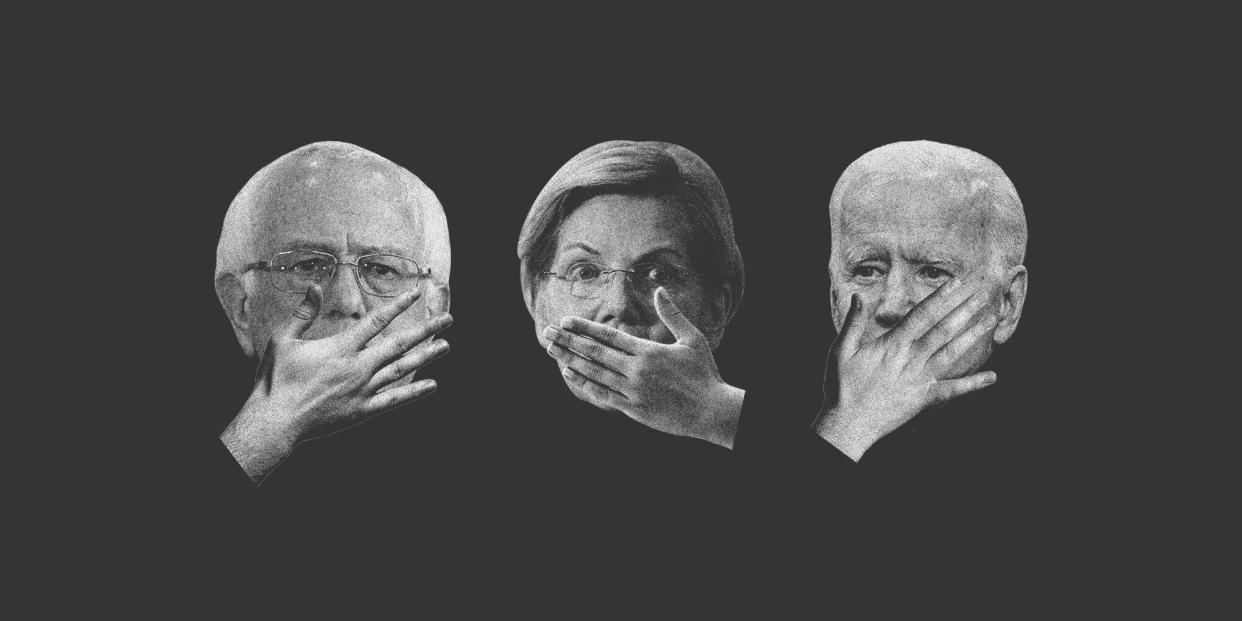

The 2020 Candidates Still Won’t Talk About The Main Cause Of Mass Incarceration

A long-overdue debate on reforming the criminal justice system has taken center stage in the Democratic presidential primary. Pete Buttigieg wants to cut the incarcerated population in half. Joe Biden, who helped to author the infamous 1994 crime bill as a senator, is urging “redemption and rehabilitation.” And Kamala Harris, a former prosecutor, just released a sweeping proposal to transform the system and end mass incarceration.

The Democratic front-runners all agree that the U.S. imprisons too many people (around 2.2 million in 2017) and that people of color have been disproportionately affected. Some, like Harris, Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, have released comprehensive plans to address the crisis, which include efforts to tackle the root causes of crime, like poverty and homelessness, and calls to eliminate the mandatory sentencing laws ushered in by the war on drugs.

But largely absent in these proposals is a public reckoning with the primary cause of America’s high prison population: violent crime. Over half the people serving time in state prisons, which house the majority of the U.S.’s prisoners, are convicted of violent offenses, ranging from robbery to murder. Yet only Harris’ proposal explicitly mentions violent crime as an underlying driver of mass incarceration. Her plan would create a commission to study the issue and make policy recommendations.

Experts interviewed by HuffPost warned that meaningful reform requires changing how the U.S. punishes violent crime, not just ending the war on drugs. They also cautioned that drawing a hard line between violent and nonviolent crime, as some candidates have done on the campaign trail, obscures a more complicated reality.

“Frankly, those who think we can eliminate mass incarceration without dealing with violent crimes are committing a math error,” said Keith Wattley, executive director of UnCommon Law, a nonprofit law firm in California. “Most of these proposals are silent on the issue of serious and violent crimes. And silence really signals acquiescence.”

In the two double-feature Democratic presidential debates to date, the candidates (and, to be fair, the moderators) have devoted scant time to criminal justice. Beto O’Rourke brought up mass incarceration but framed it around marijuana legalization. Warren went after private prisons, which house only 8% of the country’s incarcerated population. Others talked about gun violence. Criminal justice advocates hope that at the next debate on Sept. 12. candidates will be pressed for a fuller discussion.

Name The Problem

The rate of incarceration in the United States has more than quadrupled in the past four decades, and scholars are still debating why.

A 2014 report by the National Academy of Sciences attributes the rise to mandatory sentences, longer sentences, overzealous prosecutors and harsher enforcement of drug laws. Policies such as “three strikes” laws, which require sentences of 25 years to life after a person is convicted of a third felony, and “truth in sentencing” laws, which force people to serve most of their sentences before qualifying for parole, have resulted in more people spending more time behind bars.

But while the war on drugs undeniably contributed to mass incarceration, the majority of people in state prisons, which account for 88% of the total U.S. prison population, are there on convictions for violent crimes. Only 15% of people in state prisons are held for drug crimes. (Federal prisons, which house 12% of the U.S. prison population, are a little different. There, about 45% of inmates are convicted of drug offenses.)

The public is woefully misinformed about these facts. A 2016 poll by Morning Consult and Vox found that the majority of people erroneously believe that nearly half of all U.S. prisoners are incarcerated for drug offenses. When asked if they supported reducing prison time for nonviolent offenders, an overwhelming majority of respondents said yes. But only 29% felt the same way about people who committed a violent crime, even if the individual had a low risk of reoffending.

John Pfaff, author of “Locked In” and professor at Fordham Law School, believes these attitudes are intertwined.

“It’s because we believe that everyone’s in prison for drugs that we don’t have to ask these hard questions of violence,” he said. “Politicians are afraid to talk about it. So they talk about drugs and that reinforces people’s belief that everyone’s there for drugs. It’s a hard cycle to snap out of.”

Pfaff commended Harris for noting the central role that violent crime plays in driving prison populations, but said he wished she’d gone further.

“It’s worth noting that she demands action now when it comes to how we handle drugs, but pushes the issue of violence to a commission ― even though we have the data to change how we approach violence now too,” he said.

The Plans

In some ways, the current debate over criminal justice reform is historic. Most 2020 Democratic candidates are now openly opposed to the death penalty and want to legalize marijuana ― positions relegated to the fringe in past election cycles.

“The way they are talking about criminal justice is dramatically different from what we’ve heard before in a presidential campaign,” said Marc Mauer, executive director of The Sentencing Project.

He praised the candidates for thinking systemically about the causes of crime and focusing on prevention. Warren’s plan, for example, connects the dots between adverse childhood experiences, such as poverty and homelessness, and later involvement in the criminal justice system. Sanders’ plan emphasizes the need to address the social and environmental conditions that lead to crime and calls for increased funding for violence interruption models.

But to truly reduce the prison population, the U.S. needs to shorten sentences, including for violent crimes, Mauer said. That will require comprehensive sentencing reform.

In theory, a number of candidates have endorsed such reforms. Warren, Sanders and Biden, for example, have said they want to reduce or eliminate mandatory minimum laws, which require judges to sentence people to a specific prison term for a specific crime. But none of the candidates have explained what this would mean in practice: a radical rethinking of how we punish violence.

“They are not articulating what the problem is, and difficult as it is, why it needs to be addressed,” said Mauer, who proposed a 20-year cap on sentences in his book “The Meaning of Life,” arguing that many people age out of crime and pose little risk to public safety. The U.S.’s excessively long sentences are an outlier compared to much of the world, he said, and the practice is counterproductive and costly.

Reconsidering how to handle people who commit violent crimes raises complicated and uncomfortable questions. The criminal justice system is riddled with cases like this man, who served 36 years behind bars for robbing a bakery of $50 ― considered a violent crime ― when he was 22. But tougher are the cases that involve a serious injury or death. How long should someone who commits murder but who is no longer deemed dangerous be held in prison? Does it make sense for a woman who kills her abusive husband to spend the rest of her life behind bars? Should a person who sells drugs that are later connected to an overdose spend three decades in prison on homicide charges? Could some violent crimes be dealt with using alternatives to incarceration, such as restorative justice, as one group in Brooklyn is now doing?

Mauer said he was encouraged by legislation written by presidential hopeful and Sen. Cory Booker (D-N.J.) that would allow federal prisoners who have served more than 10 years of their sentence to petition a judge for a reduced sentence or early release. Crucially, the bill does not exclude people convicted of violent crimes.

Still, in the press release touting the legislation, Booker talks only about the impact of the drug war. And on his campaign website, he promises to extend clemency to individuals serving excessive sentences ― but only for nonviolent drug crimes.

The Power Of The Pulpit

Presidents have limited power to reform the criminal justice system writ large, as states and local districts set their own policies, said Pfaff, the Fordham professor. The federal government can wield some influence by offering grant money to states that adopt certain programs or policies, but ultimately, its impact is minimal.

Where presidents can do is set the agenda, he said.

“Imagine if someone like Warren or Sanders or Biden got up and said, ‘Look, we need to talk about how we punish violence. We are harsh on it in a way that baffles Europeans, in a way that flies in the face of what we know about what deters behavior, and we do it in a brutal and inhumane way that is often counterproductive,’” he said. “That statement alone would do more than any 50-page policy would do.”

Wattley, the executive director of UnCommon Law, agreed.

“It could set the tone for what people are willing to say, and what people are willing to risk,” he said.

He urged the candidates to stop making a distinction between nonviolent and violent crimes when talking about the need for reform.

The line is not as clear-cut as the public might imagine, he said. Some individuals convicted of drug crimes also committed violent crimes but pleaded to the lesser charge; some violent crimes are directly related to drug activity.

“It’s one of those false distinctions, but the underlying causes [of the crime] are often the same,” he said. “We pretend that there’s an added evil component to people who commit violence. That’s just not my experience.”

Kristen Bell, an assistant professor at University of Oregon School of Law, said she understands why candidates wouldn’t want to speak openly about changing how the country treats violence, especially as Democrats have long been branded as weak on crime by Republican opponents.

“It’s hard as a politician who wants to get elected to run on a platform of releasing people from prison who have committed murder and rape, right?” she said. But stressing the difference between violent and nonviolent crimes sends the wrong message, she added.

“It legitimizes the way we incarcerate people who commit violence and makes it seem like it’s OK and not in need of change,” she said.

“That’s just not true. We need to be talking about them because they are the majority of people in prison.”

CORRECTION: A previous version of this article stated that a man served 36 years for robbing a bank. It was a bakery.

Love HuffPost? Become a founding member of HuffPost Plus today.

This article originally appeared on HuffPost.