The Giant Disconnect Between Gun Deaths and Mental Health

Here’s a look at the correlation between rates of serious mental illness and gun deaths on a state-by-state basis. (Photo: Getty Images)

In the month since the Umpqua Community College shooting in Oregon — in which a 26-year-old man killed eight students and a professor — Congress has turned not to gun control, but mental health.

Six days after the shooting, Rep. Martha McSally, R-Arizona, sponsored the Mental Health and Safe Communities Act, a bill first introduced by Sen. John Cornyn, R-Texas, in the Senate. Backed by the National Rifle Association, the law would “enhance the ability of local communities to identify and treat potentially dangerous, mentally-ill offenders,” as well as “help fix the existing background check system" according to Sen. Cornyn’s press release. The bill has gone on to receive bipartisan support, a rare feat in today’s polarized congressional climate.

While the bill certainly has its critics — some argue that the legislation would ultimately weaken the current system — the legislation’s broad support sends a clear signal: Congress believes addressing mental health concerns, not enacting stricter gun control, will serve as the best response to the latest round of gun violence. But does the data support this decision?

Recently, we evaluated President Obama’s claim that “states with the most gun laws have the fewest gun deaths.” With all types of gun deaths included, including suicide, he’s right. But several other factors complicate the president’s statement. When you remove suicides, the correlation still holds, but becomes much weaker. If you count only by mass shootings, the correlation disappears — for example, California has more than its fair share of mass shootings (nine since 1984) despite having the strictest gun laws in the nation. Still, there’s enough data to suggest that gun violence does indeed tend to drop alongside stricter gun laws.

Does the same trend hold for mental health? At HealthGrove, we wanted to perform a similar study, this time looking at the correlation between rates of serious mental illness and gun deaths on a state-by-state basis. The data comes from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

(Image: Graphiq)

We see the highest rates of mental illness in Utah, Arkansas, West Virginia and Vermont. The Pacific Northwest, Rust Belt and Bible Belt also exhibit higher-than-average rates. Meanwhile, California, Illinois, New Jersey and Connecticut have among the lowest rates of serious mental illness.

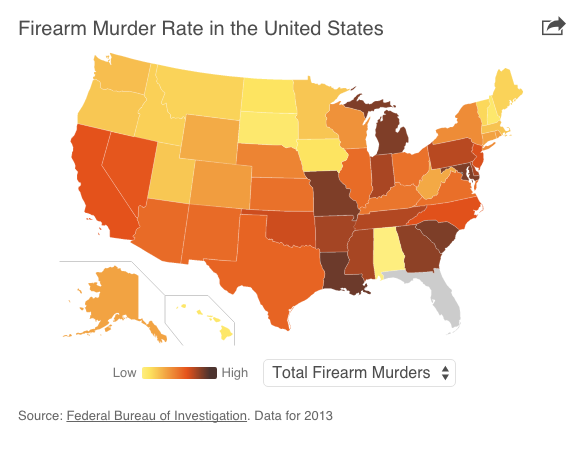

Now consider firearm-related deaths:

(Image: Graphiq)

The picture here is mixed. Big states like California, Texas and New York seem to confirm Congress’ hypothesis, as each state features a low rate of mental illness next to a low rate of firearm-related death. But several more states fly against the theory. Oregon, Washington, Colorado and Vermont all boast mid to low rates of firearm deaths, despite having high rates of mental illness.

But what about the same map with suicides removed, as advocated by the Washington Post? Here, we turned to data from the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

(Image: Graphiq)

With this map, there’s even less evidence to suggest that mental illness and firearm murders go hand in hand. In fact, for several regions, the opposite trend emerges: namely, that low rates of mental illness tend to accompany high rates of firearm-related homicide. The discrepancy is particularly notable in the West, the South and the Northeast.

Data from the National Center for Health Statistics further refutes the connection between mental health and gun deaths. According to its database, fewer than 5 percent of the 120,000 gun-related killings from 2001 to 2010 were committed by people diagnosed with mental disorders. In fact, as John Oliver pointed out on his HBO program “Last Week Tonight,” mentally ill people are much more likely to be gun victims, not perpetrators.

So why is Congress so focused on mental health when it comes to addressing gun violence?

For one, mental health is a safe and popular issue, particularly compared to gun control. Nearly all Americans agree that mental health is a problem, and over 70 percent believe the nation needs to make “significant” or “radical” changes. In contrast, less than half of Americans support stricter gun laws.

Next, mass shooters routinely come across as mentally ill in the news — their diaries, plots and final statements subject to hours of media analysis and social media discussion. Trained psychiatrists might tell us that a given shooter was sane, but to the average American, anyone who commits a mass murder qualifies as mentally disturbed.

But even if you assume that most mass shooters are indeed mentally ill — whether diagnosed or not — mass shootings make up less than 1 percent of all gun deaths in America, according to a study by the Pew Research Center.

If there’s any data that supports the connection between gun violence and mental illness, it’s suicide. People with mental illnesses are about 12 times more likely to commit suicide, and suicide-by-firearm is by far the most deadly method. More than nine in 10 attempted suicides involving a firearm are successful. In contrast, less than half of pill- or poison-related suicide attempts result in death.

As Dr. Jeffrey Swanson, a professor in psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Duke University School of Medicine, put it recently: “Mental illness is a strong risk factor for suicide. It’s not a strong risk factor for homicide.”

Perhaps the Mental Health and Safe Communities Act can help chip away at suicide rates by removing guns from an at-risk population.

But as a response to mass shootings and gun-related murders?

The data doesn’t back it up.